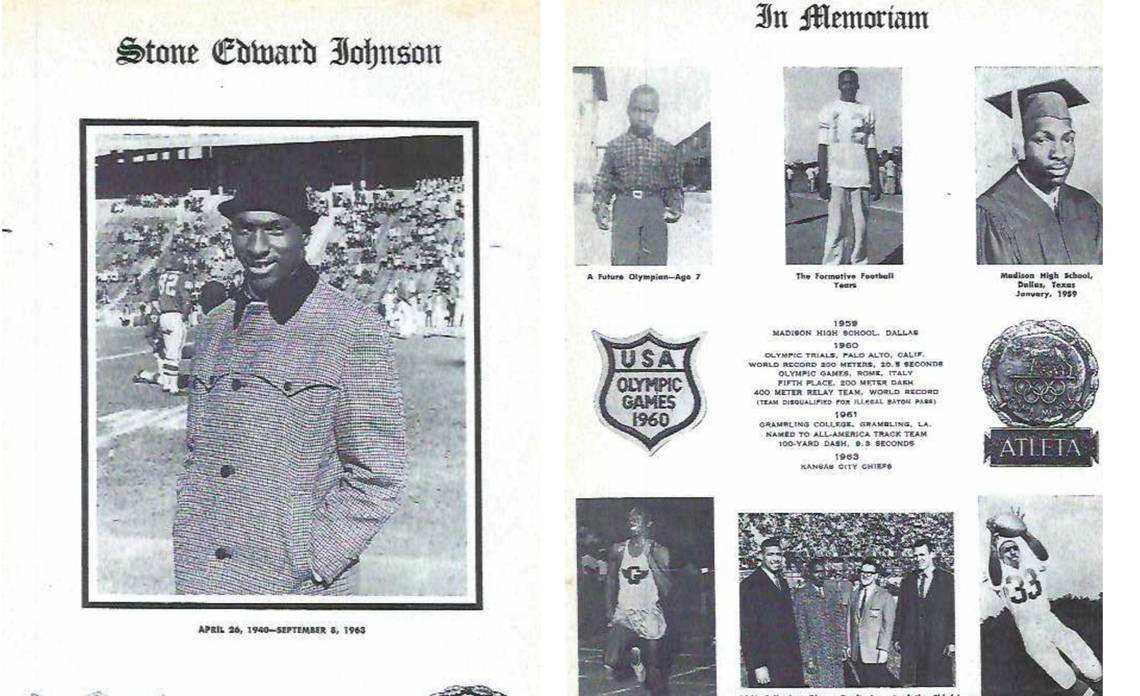

In another life, Stone Johnson might have joined 1963 AFL Draft classmates Buck Buchanan, Ed Budde, Bobby Bell, Jerrel Wilson and Dave Hill in helping forge a dominant decade for the Chiefs.

The whirlwind who tied a then-world record (20.5 seconds) in the 200-meter dash in the summer of 1960 and ran the third leg of the U.S. 4×100 relay at the Rome Olympics could have been the forerunner of Tyreek Hill.

But Johnson, alas, never played a regular-season game for the Chiefs. The rookie from Grambling State died days after suffering a broken neck in the final preseason game in their first year in Kansas City after moving from Dallas.

My thoughts turned swiftly to Johnson on Monday night as we watched the Buffalo-Cincinnati game with the anguish that anyone with a heart had to feel seeing Damar Hamlin’s collapse and the devastation of his Buffalo teammates.

The NFL has said Hamlin went into cardiac arrest in the seconds after a collision with Cincinnati’s Tee Higgins. He remained in critical condition as of Tuesday night.

Amid the talk about how this life-threatening scene supposedly was unprecedented on a pro football field, I thought about the similarities and differences between this and the fate of Johnson.

About how much has changed in preparedness and sophistication of treatment and medicine … and yet how much surely remains the same in terms of the impact on those closest to someone suffering a catastrophic injury.

And about how what happened to Johnson in Wichita on Aug. 31, 1963, at least in some small way, helped create awareness that carried forward helped to give Hamlin a far better chance than Johnson had.

When Johnson’s head went into the thigh of a Houston defender and he crumpled to the ground that night, there was no ambulance on site.

In fact, as Michael MacCambridge wrote in his biography of Lamar Hunt, “There was no one on either sideline prepared to administer first aid for the convulsive trauma that Johnson had suffered.”

That’s in stark contrast to the virtually instant CPR and other measures immediately taken with Hamlin, for whom an ambulance was on the field within minutes.

Each obviously required entirely different treatment.

But you can be sure that the looks on the faces of teammates at the exhibition game attended by 11,000 people would have looked much like the forlorn faces of the Bills and Bengals that millions saw on national television.

Faces of the Bills in particular that left you not only sure they couldn’t and wouldn’t resume play that night, but even wondering how soon they could truly be emotionally prepared to play again.

The Chiefs were like that that night in 1963 … and all the more after their worst fears were realized and Johnson died eight days later.

When I spoke with Len Dawson about it 50 years later, he talked as if Johnson had just died.

“That was awful,” said Dawson, one of the pallbearers at the funeral in Dallas. “It affected a lot of the players. It was on their minds (all season), maybe until this day.”

On the sidelines that night, two young sons of coach Hank Stram cried as Johnson lay prone, unable to move his legs. The coach was “hysterical,” his son Dale said by text Monday night, yelling and screaming for doctors.

Star running back Abner Haynes, who helped persuade the Chiefs to pursue Johnson, was tormented by Johnson’s death. In 1991, he told The Star, “I was the cause of him being here. I felt responsible for him being there and getting killed.”

Haynes said it took the ambulance 90 minutes to get there. But several news sources and observers put it at more like 20 to 30 minutes.

Either way, it was entirely too long. As they agonized in waiting, tight end Fred Arbanas was among those trying to comfort Johnson without knowing how he could best help.

“He was dazed, and I slid his helmet off him like most guys did back then,” Arbanas, who had assumed Johnson had his “bell rung,” told me in 2013.

All those years later, Arbanas still was grappling with what he couldn’t have known then.

“Maybe that’s what really, you know, got to him. Or maybe it wasn’t. I don’t know,” said Arbanas, who died in 2021. “It was a hell of a collision that he had and one of (those) things you try to help somebody. And maybe what you did did or didn’t help. I’ve thought of that several times in the past.”

Also astonishing in the context of today: After the injury in the first quarter of a preseason game, the Chiefs and Oilers played on … even as Johnson had gone into surgery for a fracture of the fifth cervical vertebrae in his neck and spinal cord.

Afterward, Dale Stram recalled, his father and some players went to see Johnson in the hospital before returning to Kansas City. His father was in tears when he came back out.

Lamar Hunt stayed at the hospital and soon greeted Johnson’s parents, who arrived in Wichita that night on a private plane furnished by Hunt and remained there until he died on Sept. 8.

Since Johnson’s death, he has been commemorated by a franchise that retired his jersey No. 33 and struggled that season. A year after winning the AFL Championship, the Chiefs won just two of their first 11 games and finished 5-7-2.

To Dale Stram’s understanding, there was an ambulance at every Chiefs game thereafter. That couldn’t be immediately verified, and it’s unclear when the NFL began mandating that.

But Johnson’s death almost certainly was part of the beginning of a transition toward the top-notch care we see today … and that was so crucial in at least the first 24 hours since Hamlin’s collapse.

Johnson’s death, though, wasn’t the only tragedy connected to an on-field event in the early years of the Chiefs here.

Only two years later, Dawson gave the eulogy at the funeral of another young teammate: running back Mack Lee Hill, who suffered a knee injury at Buffalo and died in surgery two days later after he developed hypothermia (108 degrees) in reaction to anesthesia.

According to accounts at the time by The Associated Press, an autopsy revealed that Hill suffered “a sudden and massive embolism after surgery.”

Like Johnson, Hill is honored by the organization with a retired jersey (No. 36). And the Chiefs annually present their best first-year player with the Mack Lee Hill Rookie of the Year award.

As if that weren’t plenty to contend with in the first three seasons in Kansas City, rookie linebacker Willie Lanier in 1967 collapsed on the field against Houston a week after taking a knee to the head against the Chargers.

Lanier was out for two hours, he told me in 2020. But he wouldn’t learn until a decade later that team physician Albert Miller had lost his pulse three times on the way to the hospital.

In an ambulance, it should be noted, which may or may not have otherwise been readily available if not for the horror story of Johnson.

Lanier was later diagnosed with a subdural hematoma, which led to him radically changing his tackling technique and philosophy to “never have any head impact at any time, anywhere.”

Lanier, of course, went on to a Hall of Fame career, contradicting the lingering notion that you can’t be a successful tackler without head contact — the most pervasive issue in the NFL and football in general as we’ve come to learn so much more about CTE and head injuries.

When replays showed Hamlin standing up and then collapsing after the play, I initially thought of Miami quarterback Tua Tagovailoa staggering and falling after getting up against Buffalo.

But as we watched the piercing reactions of the players, we had to confront the reality that he may have died or be dying before our eyes.

Thank goodness we can still cling to hope for Hamlin’s survival and return to health as we wait to better understand exactly what happened.

To what degree was it a reflection of what makes us shudder over the violence of the game? And to what degree was it attributable to something such as freakish timing that could have caused the condition of “commotio cordis,” as described by The Washington Post, with a blow struck in a 40-millisecond window of the heart’s electrical cycle?

But no matter how distinct Hamlin’s case proves to be and no matter what happens from here, the shattering scene still should serve as a poignant reminder that the dire moment on Monday wasn’t a first.

Several pro football players have died from events connected to injuries in a game, and Detroit’s Chuck Hughes died on the field after suffering a heart attack in a 1971 game against the Bears. In 1978, New England’s Darryl Stingley was paralyzed in a preseason game by Oakland’s Jack Tatum.

To say nothing of severe injuries and deaths at other levels of the game or active players away from the game (such as Joe Delaney) and in numerous other sports.

Monday also reiterated the vulnerability of the high-profile athletes we so often put on a pedestal or criticize as if they weren’t human, too.

They not only bleed like the rest of us, as it happens, but sometimes they cry like us, too.

And while many of us hold Hamlin and his family and the Bills close to our hearts right now, here’s to also never forgetting those so few saw.

Remember Stone Johnson and Mack Lee Hill … and what might have been in another time and place for each.