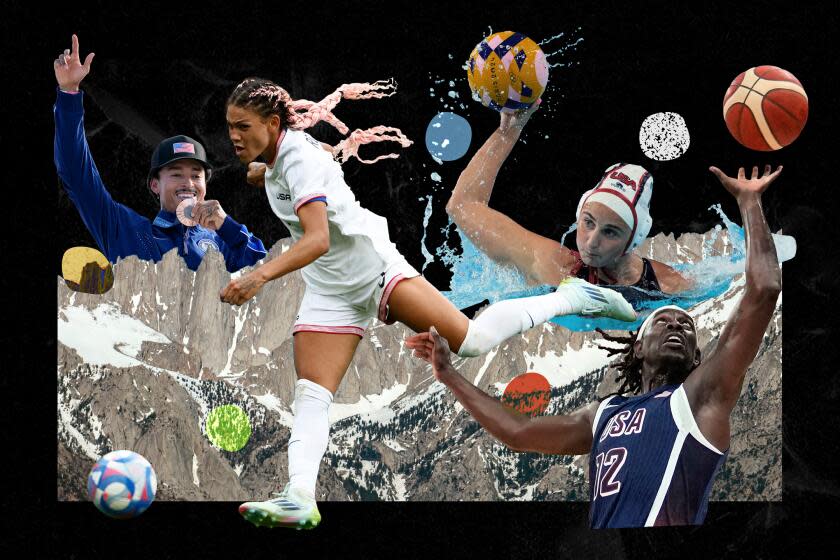

The U.S. soccer team, which will play in the women’s gold-medal game at the Paris Olympics on Saturday, has five players from California. All four U.S. beach volleyball players who advanced to the quarterfinals are Californians, as are 11 of the 13 women on the water polo team, who advanced to the bronze medal game.

In fact, everywhere Team USA has competed in these Paris Olympics, chances are a Californian or three were involved. One hundred twenty-one of the 594 athletes on the American team — more than one in five — are from the state. And that doesn’t include the California natives who competed for other nations, such as Trinidadian swimmer Dylan Carter, Filipina gymnast Emma Malabuyo and Japanese tennis player Ena Shibahara.

Not only is no state better represented in France than California — fewer than 24 countries have more Olympians in these Games than California. And the reasons are simple, said David Wallechinsky, president of the International Society of Olympic Historians and a native Californian.

“Obviously it’s the weather,” he said. “But also it’s the universities. People from other states come to UCLA, USC and Stanford and they stay. Having good coaching at the universities really helps attract people to California.

“And then the other factor, which I think is really important, is that it’s role models. You grow up in Minnesota or Vermont, your role model, if you have any in sport, is not going to be an Olympic summer sport [athlete]. But if you’re Californian, it’s going to be. Or it’s more likely to be.”

The population is also a plus. With 39.5 million residents, California has 10 million more people than the next most-populous state, Texas. As a result, the number of kids playing high school sports in California last year was larger than the number of people living in Wyoming, Vermont, Alaska or North Dakota.

Bob Larsen, a former track coach at UCLA, also credits the state’s geography, which allow athletes to train at sea level or on the slopes of Mt. Whitney, the highest mountain in the contiguous 48 states, on the same day. California, he said, also has excellent facilities and a robust system for finding and grooming young athletes.

“Youth clubs and middle and high school programs identify and encourage talented athletes early,” said Larsen, who coached at the club, high school and college level, helping Deena Drossin of Agoura Hills to a marathon bronze medal in 2004. “Many college and university teams with good coaches grow the sport.”

And the schools take that mission seriously, even if it doesn’t just benefit Team USA. Stanford, for example, sent 60 Olympians, representing 15 countries, to Paris. UCLA sent 40 athletes from 18 countries and USC 66 from 26 nations. Even UC Irvine had four former athletes in Paris and Santa Barbara City College one.

Read more: U.S. women’s water polo team beset by tragedies keeps rare Olympic loss in perspective

“We place a significant emphasis on the development of Olympians and other world-class competitors,” said Stanford athlete director Bernard Muir, whose school, if it were a nation, would have finished 11th in the medal count in Tokyo and 10th in Rio de Janeiro. “Several of our peer institutions throughout the state operate the same way. We take tremendous pride in things like leading the medal count among colleges.”

Mark S. Dyreson, professor of kinesiology and history and the co-director of the Penn State Center for the Study of Sports in Society, said California’s rise toward becoming an Olympic power took root about a century ago when the state — and especially Hollywood — began to alter the country’s culture.

California was seen as a land of affluence, fashion, celebrity and new ideas — no matter that much of that was a facade. So when Los Angeles hosted the 1932 Olympics, whose scale and quality were beyond anything that had come before, sports became an indelible part of that brand. Hollywood’s film industry, which heavily promoted the Los Angeles Games, then sold that brand to a global audience.

A boom in swimming pool construction tied to the post-war suburbanization of the state was another factor popularizing an idealized California lifestyle built around leisure and recreation. (It’s also why the state has traditionally produced more Olympic swimmers than any other, though just two Californians, male butterfly specialist Luca Urlando and relay medalist Abbey Weitzeil, were part of this summer’s team.)

More recently, the addition of sports such as skateboarding, beach volleyball, table tennis, badminton, golf and surfing, which have long been ingrained in the California culture, has also swelled the number of Olympians from the state. Thirty of the 44 U.S. Olympians in those sports come from California.

“You know, another thing is, I’ve been reading been reading a lot of the [athletes’] biographies. There’s one thing that comes up over and over again, and it’s very strong, which is the parents,” Wallechinsky said. “They’ve got an overactive kid, and they’ll just enroll them in five or six different sports, and then eventually one takes. It’s not so much that the parents are pushing them, they’re just giving them a lot of opportunities. And they find something they like.

“Part of it is the enthusiasm.”

And part of it is the competition. Trinity Rodman of Newport Beach, whose three goals in the Olympic soccer tournament are tied for the team lead heading into the women’s final Saturday, said it’s nice to have weather that allows you to play year-round. But what really made her better was being matched against talented players growing up in South Orange County.

Read more: Sophia Smith goal propels U.S. past Germany, Americans clinch spot in Olympic final

“The clubs that I faced in California were good, like, really good, and top level,” she said. “I don’t know what it was. I can only speak to my experience. [But] we played a lot of good teams, which was nice.”

California just seems to breed stronger, healthier people, which even makes the non-athletes better, something Wallechinsky learned after taking a physical fitness test in junior high.

“I saw the results and I was way down in my school. Way, way down,” he said. “Then they released the national results and I was like, in the top 5%. Wow, I guess I’m not so bad after all.

“Even at the age of 13, it gave me a perspective how different California was than the rest of the country when it came to youth sport.”

Sixty-three years later, that hasn’t changed. And the US. Olympic team is reaping the benefits.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.