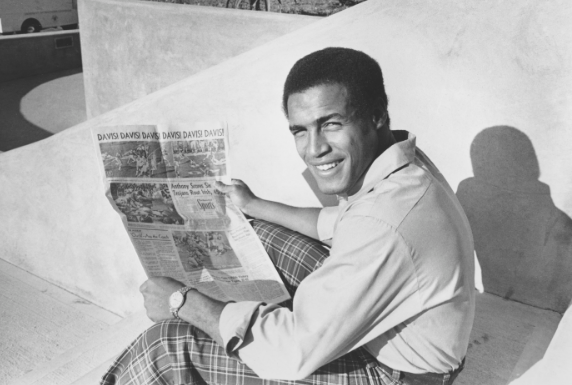

Fifty years after the game that changed his life, Anthony Davis sits in an office surrounded by a museum of his USC memorabilia, wondering what might’ve been if his biggest moment never materialized.

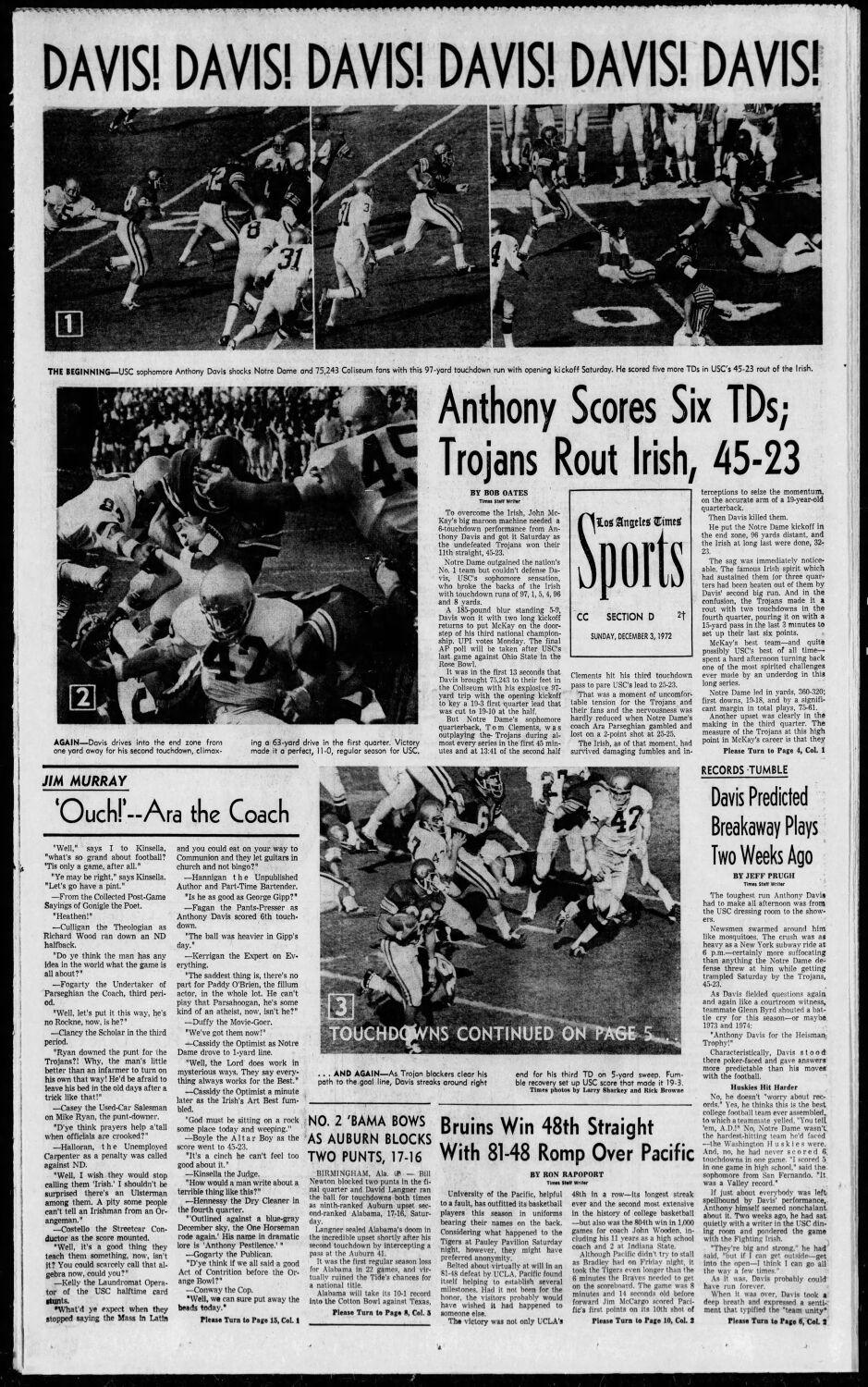

The six touchdowns Davis scored on Notre Dame that day in December 1972 would go down as one of the greatest single-game performances in college football history, the piece de resistance of a storybook ‘72 season for USC that still ranks among the best the sport has ever seen. On that particular subject, there’s no debating with Davis, whose infamous swagger as a star Trojan running back remains very much intact at 70 years old.

“We set the standard. No one has lived to that standard yet,” Davis declared.

Not even the 2004 Trojans with Reggie Bush? Davis shakes his head. He wonders if the 1972 Miami Dolphins, who finished 17-0 that NFL season, could keep up.

“Pound for pound, we were the best team ever,” he says.

The case is a pretty convincing one, if you’re willing to adjust for generation: The 1972 Trojans finished 12-0, riding that resounding win over rival Notre Dame to the Rose Bowl, where they steamrolled Ohio State to secure an unbeaten season and undisputed national title. Along the way, USC left little room for doubt about who reigned supreme in ‘72. The Trojans never once trailed in the fourth quarter, opting instead to demolish opponents by an average of nearly four touchdowns per game.

That season — and that Notre Dame win especially — have followed Davis ever since, through his winding pro career and its subsequent ups and downs, through airports and restaurants and real estate transactions. After a half century, some USC fans are still eager to ask about those six touchdowns. And he’s often happy to oblige.

But this week, as USC prepares to face Notre Dame and another visitor asks the running back to reminisce, Davis looks back on that long-ago title run through a slightly different lens. He can’t help but wonder about the direction it led his life — and how easily it all might have been different. What if the two running backs ahead of him hadn’t gotten hurt? Where might he be now?

Truth is, at the start of that storied ‘72 season, his focus was shifting toward baseball. He’d been City Player of the Year in both sports at San Fernando High, but playing pro ball had always been the plan. He’d already been drafted by the Baltimore Orioles as an outfielder the previous spring. On USC’s football team, he was buried behind Rod McNeill and Allen Carter in his first year on varsity as a sophomore.

“If those guys don’t get hurt and I don’t do what I do, I’m going baseball,” Davis said. “That’s how I’d started to think.”

Davis jostles two gold championship rings, from 1972 and 1974, between his fingers as he considers an alternate history, one where he never became known as the “Notre Dame killer.” Part of him still wonders where baseball might’ve taken him, had he continued playing after college, where he added three more rings to his collection under famed coach Rod Dedeaux. But USC football — and those six scores specifically — made him a star.

Fifty years later, Davis’ unexpected rise remains a key note in the triumphant story of that 1972 title run.

But talk to those who are still around from that team, and you’ll start to see just how many other fortunate twists of fate were required to write one of the greatest seasons in college football history. Some say it was a fight that brought them together. Others wonder if those Trojans were touched by God.

“The story is so great,” All-American tight end Charle Young says, “that after 50 years they’re still talking about it.”

The details may have blurred over those five decades. But depending on who you ask after all these years later, the finest USC football team ever assembled first came together through either the divine power of prayer or a sideline-clearing brawl.

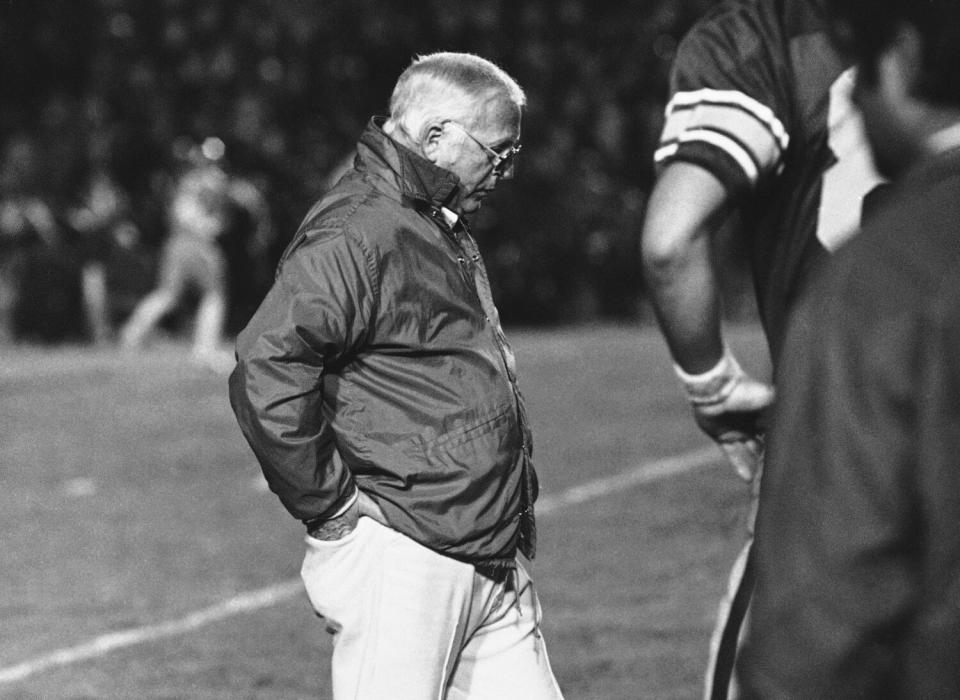

Either way, many of the ‘72 Trojans can agree generally on when it happened: October 1971, Notre Dame week. USC had lost three in a row for just the second time in John McKay’s tenure.

“They had been to four Rose Bowls in a row, and we were expected to keep it going,” said Mike Rae, USC’s starting quarterback, “and it went into the tank.”

The Trojans were spiraling at 2-4 ahead of their trip to South Bend, where Notre Dame, a 28-point favorite, was expected to roll over its rival.

“We were really circling the drain,” said Mike Ryan, who was a junior guard in 1971.

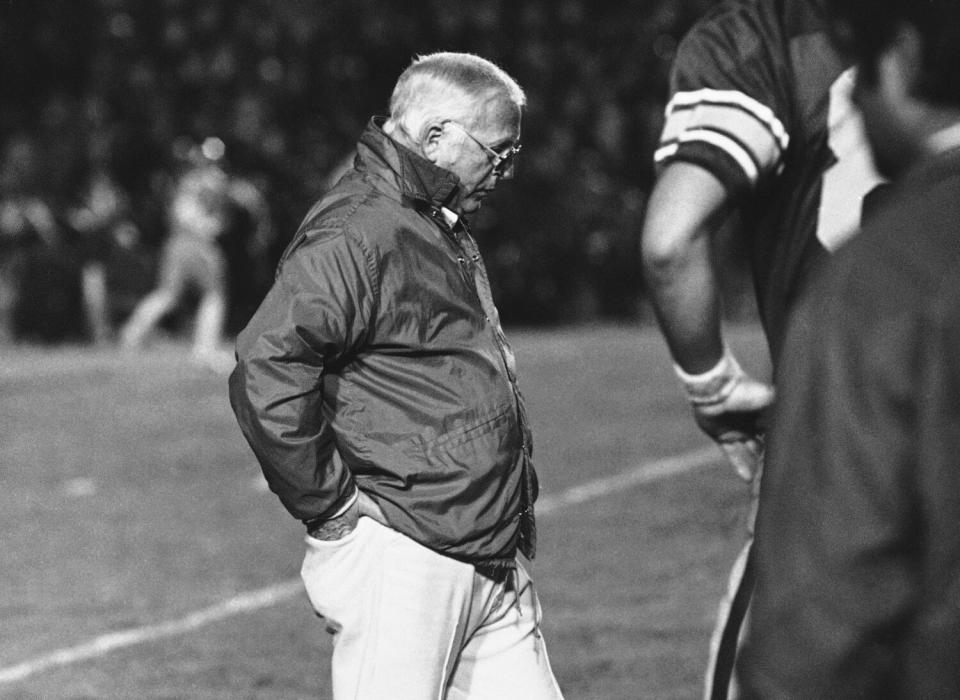

After a brutal loss to Stanford, players expected fire and brimstone from McKay, who was hardly the warm, cuddly type. What they got instead was the calmest version of the coach they could recall.

“The coaches backed off,” said Dave Brown, USC’s center on that team. “They took off the pressure and made it fun again.”

The past two years had been especially tense for some, namely Black players on the team. While USC football was at the time portrayed as a picture of racial harmony, the Trojans’ famed — and often embellished — 1970 trip to Alabama hadn’t suddenly solved the nation’s unrest over race.

McKay was “ahead of the curve” in that regard, Young said. But not all of the USC community was so welcoming.

“He was catching hell,” added Davis. “But he didn’t care what color you were, long as you could play.”

J.K. McKay recalls one Christmas Eve, just before he joined the team, when FBI agents showed up at the McKay’s home. Threats had been made against the family after his father started Jimmy Jones, who is Black, as USC’s quarterback.

In the Trojans’ locker room, Young says there was “a racial divide”. He’d come to USC, he said, because he’d watched two Black players win the Heisman Trophy as Trojans. But when he stepped onto USC’s campus, it felt like entering a foreign land. “I was thrust into affluence,” he says.

Sam Cunningham, the Hall of Fame fullback on that team, recalled to The Times in Aug. 2016 that Black and white players could be tentative and awkward with each other.

It would take time to build trust. Ryan, who is white, said some white players held misconceptions about their Black teammates, which were later hashed out during an offseason meeting.

“We were part of the experiment,” Young said. “We had to find ourselves.”

The breakthrough, some say, had to come from a higher power. The week of the Notre Dame game, a USC student assistant invited a small group of players, including linemen Ryan, Brown and Allan Graf, over to his campus apartment to pray. They prayed for a sense of unity. Soon enough, the group came to include Young and other Black players, who’d grown up in the church. Common ground was found.

“There’s a verse that we used from the book of Colossians, chapter three, verse 23,” Ryan said. “It says, ‘Do your work heartily for the Lord rather than for men.’

The message resonated. McKay wasn’t sure at first what to think of the group, Graf says. But as wins piled up from there, the pregame prayer group grew. Fifty years later, it still lives on via Zoom. A handful of players went on to actually become clergy.

The trip to Notre Dame also brought the team together through another, less harmonious method. USC had exploded for 28 points in the first half, when near the end of the quarter, Rae fumbled. A scrum for the ball turned into a scuffle between players. Soon enough, the sidelines emptied and a brawl broke out.

The fight lasted around 20 minutes, a sea of swinging limbs and thrashing bodies broadcast for all the nation to witness. Coaches even got in on the action.

“I remember this flash, a red jacket comes sprinting across and tackles a Notre Dame guy, and I’m thinking oh my gosh, that’s [USC assistant coach] Marv Goux,” Brown said.

State troopers were eventually called onto the field to break up the fight. But not only had USC already pummeled Notre Dame into submission, it’d found something else amid the melee.

“That brought the team together,” Young said. “When you go into battle, there is no atheist in the foxhole. … It took a while for that ‘72 team to come together. It took almost three years. What you saw was the culmination. You saw the fruit bearing of that tree.”

Days later, as McKay gathered players together for film study of the Notre Dame win, the coach turned on tape of the fight instead.

“Everybody was just laughing,” Rae said. “… It was a real kick.”

The Trojans did not lose a game for another two years.

Still, the pressure was mounting ahead of the ‘72 season, especially for USC’s legendary coach. McKay, who’d already won two national titles, wasn’t exactly on the chopping block. But his family wasn’t feeling secure after consecutive 6-4-1 seasons, either.

“1970 and 1971 had been two of my dad’s worst teams,” said J.K. McKay, the coach’s son who was a sophomore receiver in 1972. “There was a thought in my house that we’re gonna end up having to move to Nebraska or something.”

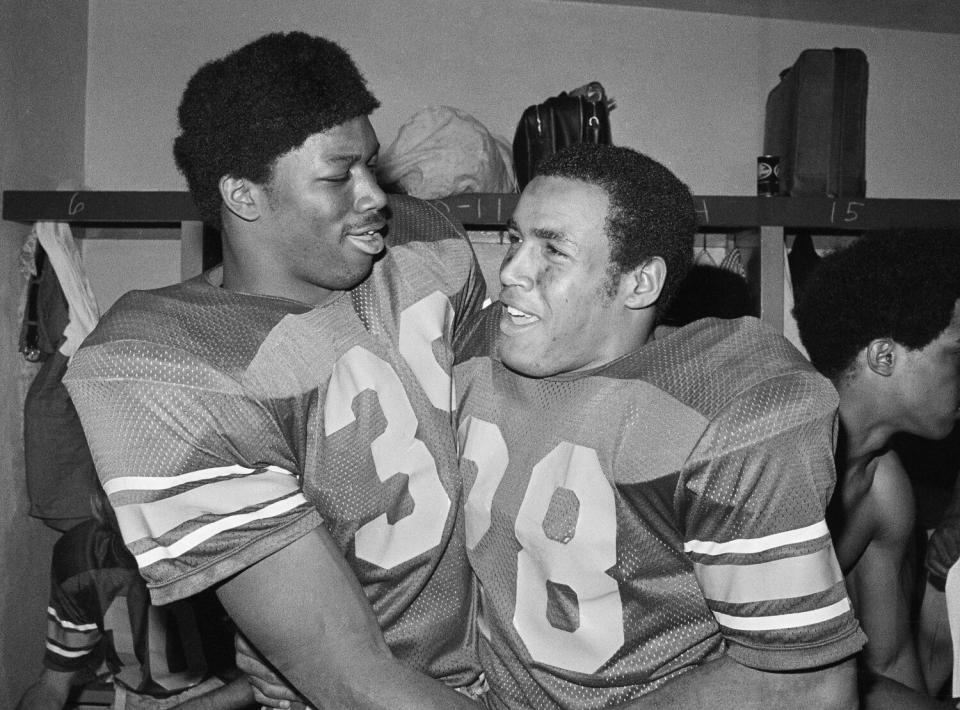

But the team had grown closer through the offseason, before a fleet of talented sophomore reinforcements arrived in the spring. Among them, the first three-time All-American in college football — linebacker Richard Wood — and a brash, young running back whose confidence already towered over the rest of the Trojans’ locker room.

“[Davis] had what we call panache,” Young says, with a laugh. “He knew he was good.”

“Everybody said I was arrogant,” Anthony Davis recalls. “I said, ‘Well, you have to be that way to run like I do.’”

So talented was the Trojans backfield that Davis started the season as the third-string tailback, behind McNeill and Carter, both of whom were former track stars. Then there was Cunningham, who was often relegated to the dirty work, despite being an All-American.

“We were three deep in every position and all those guys could’ve been All-Americans,” Davis says. “I was the slowest tailback on the team.”

Had the other two backs not been injured, Davis also may never have gotten his chance. The Trojans trounced Arkansas on the road in their season opener, and the offense kept rolling from there. They scored 50 points or more in each of the next three games, a feat even the explosive 2022 Trojans have yet to match. A nine-point win over Stanford would be the closest any team kept the final score all season.

“We started beating people just for scheduling us,” Young said.

Defensive tackle John Grant recalls looking up in the stands during a blowout win at Washington, wondering what it might take for them to lose.

“It goes through my mind that unless some sniper is in the stands and starts picking off our players, we’re going to beat these guys no matter what,” Grant said. “That was my feeling pretty much from that game forward.”

It wasn’t until the eighth game, during a wet day in Oregon, that injuries forced USC to call upon its confident sophomore back. The game was scoreless until the third quarter, when Davis took a pitch 48 yards for a touchdown. He was still catching his breath, Davis said, when he took another toss 55 yards to the end zone. He finished with 206 yards and never relinquished the lead role again.

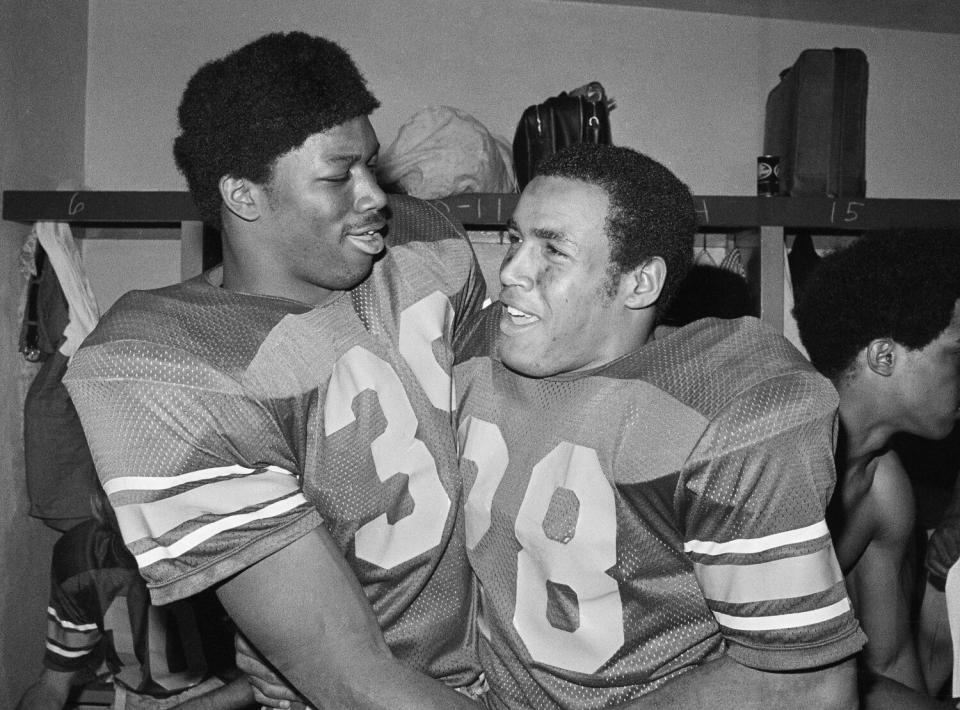

While Davis emerged as the centerpiece of the offense, Cunningham continued to dutifully do the dirty work, blocking for USC’s lead back.

“That’s quite a sacrifice to make,” Rae said. “He never got any reward for that. It isn’t getting your name in the paper, taking out linebackers for Anthony Davis. But he had so much respect from the guys around him.”

Later, McKay would call Cunningham “the best runner I ever ruined.” In the Rose Bowl that season, McKay handed the ball to his fullback four times on the goal line for touchdowns — a small token of his appreciation.

But Davis had a way of monopolizing the spotlight. With the Notre Dame game approaching, he told a Times reporter that he would “go all the way a few times.” His teammates weren’t thrilled with the prediction.

“They told me I should’ve kept my mouth shut,” Davis said.

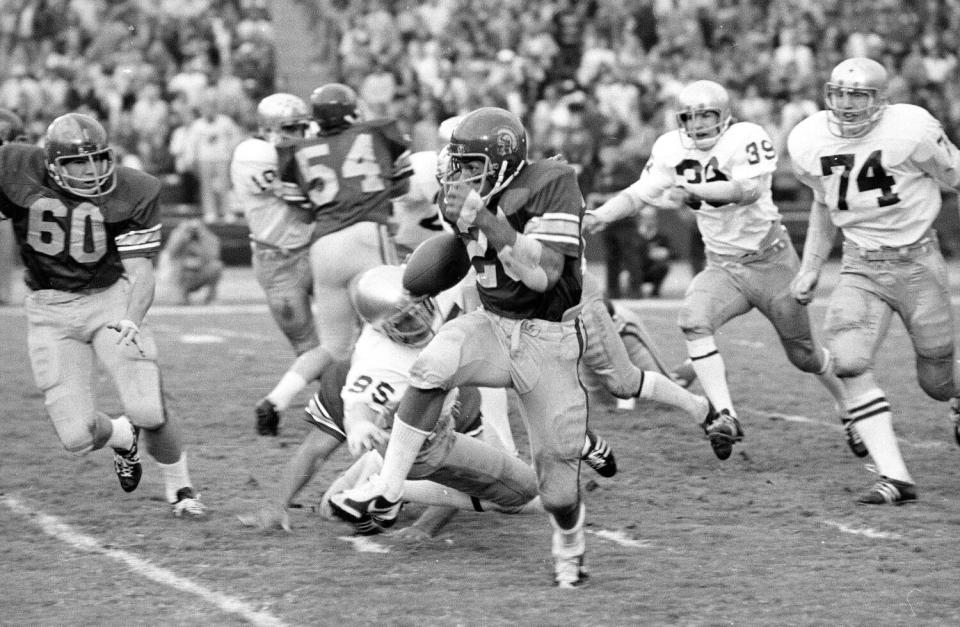

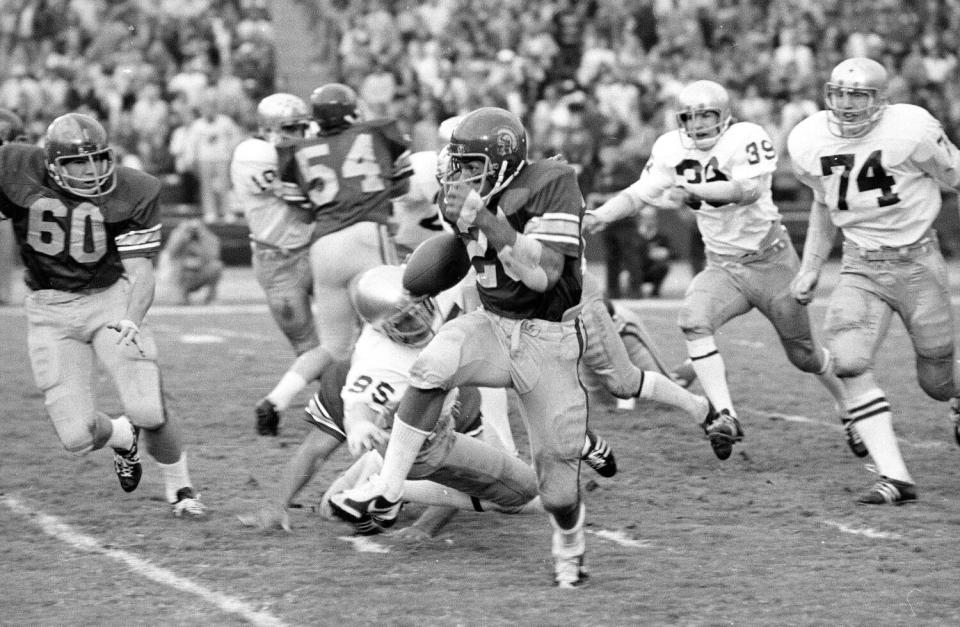

But he’d waste no time backing it up. Davis caught the opening kickoff against the Irish, spotted a crease, and exploded into the open field, sprinting 97 yards for his first score. “That’s one,” he thought to himself.

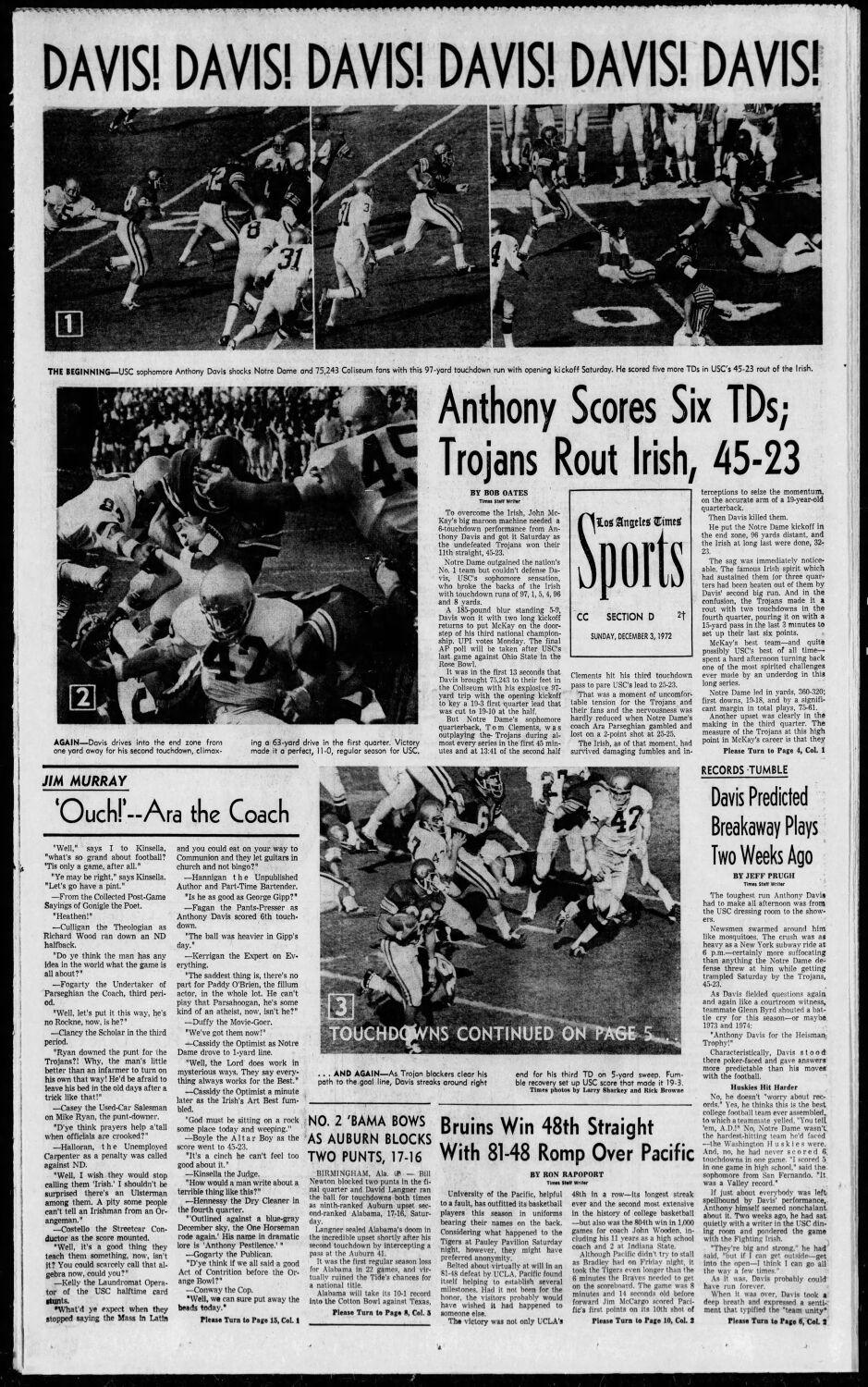

It was just the start of a nightmarish afternoon for Ara Parseghian and the Irish. One after another, the Trojans back piled up touchdowns, blowing past his prediction before halftime.

His second kick return score, late in the third quarter, would be the back-breaker. Notre Dame had cut the lead to just two points. But after sending the previous kickoff out of bounds, Parseghian ordered the Irish to kick it deep. It went to Davis instead. He slipped past one Irish defender, then danced around another on his way to the end zone, a 96-yard touchdown return.

Davis finished with 368 all-purpose yards to go with his six scores, before he was subbed out in the fourth quarter. “I know I could’ve had more,” he says today.

He’d get his chance soon enough. Davis scored another in a loss to Notre Dame the next season, ending the Trojans’ unbeaten streak that was sparked by the brawl in ‘71. He’d add four more in ‘74, helping USC mount a miraculous comeback on their way to another national title.

But his world changed with those six scores in ‘72. “It was bedlam for me, everywhere I went,” Davis said. He put any thought of quitting football behind him.

For USC, that day was a coronation. A win over Ohio State in the Rose Bowl would secure an undefeated season and undisputed national title. But there were no trophies to be lifted in those days, no grand announcements to declare what those Trojans already knew, deep down.

“At that point,” Davis said, “we were the greatest team ever.”

Fifty years later, with USC at the start of its own national title push, members of the ‘72 team gathered for a reunion dinner on Oct. 7 in Long Beach. (The next day, during halftime of USC’s game against Washington State, the team was recognized.)

They traded old stories. They talked about the injuries that lingered and the teammates they’d lost in the years since. They shared pictures of their grandkids. They even reminisced about the fight in ‘71.

“They all still remembered where they were and what part of the fight they were in, who they punched and who punched them,” Rae said.

While some still gather for Bible study, others hadn’t seen each other in decades.

“Richard Wood was still talking trash like it was 50 years ago,” Davis said, with a laugh.

But as they sat together, trading tales from that team over steak dinner, they didn’t talk much about the lasting nature of that legacy.

No one felt the need.

“You know what they say,” Young said. “If what you do speaks so well, I need not hear what you say. And what we did spoke so well they’re still talking about it 50 years later.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.