The way the clouds never formed in an ocean blue sky, the way the afternoon sun hit the San Gabriel Mountains, the way one of baseball’s truest cathedrals was dropped right into the center of it — this was Dodger Stadium at its heavenliest.

“It was a postcard,” Dodgers first baseman Steve Garvey said.

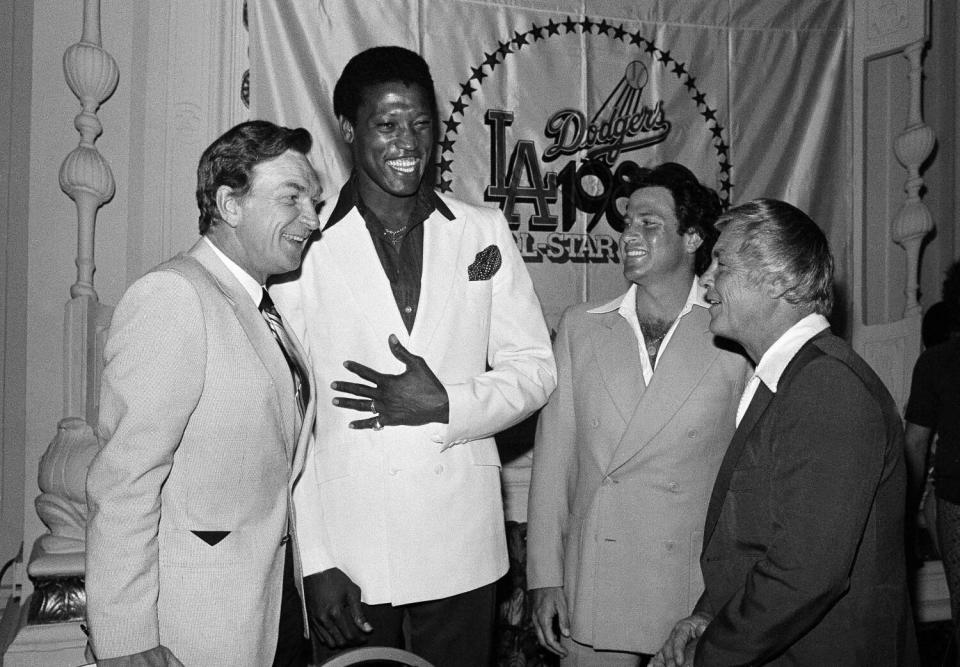

More than 36 million people — roughly one in every six Americans — received that postcard when they watched the 1980 All-Star Game on TV. Another 56,088 were in the stands.

“Everything was just perfect,” Seattle Mariners pitcher Rick Honeycutt remembered.

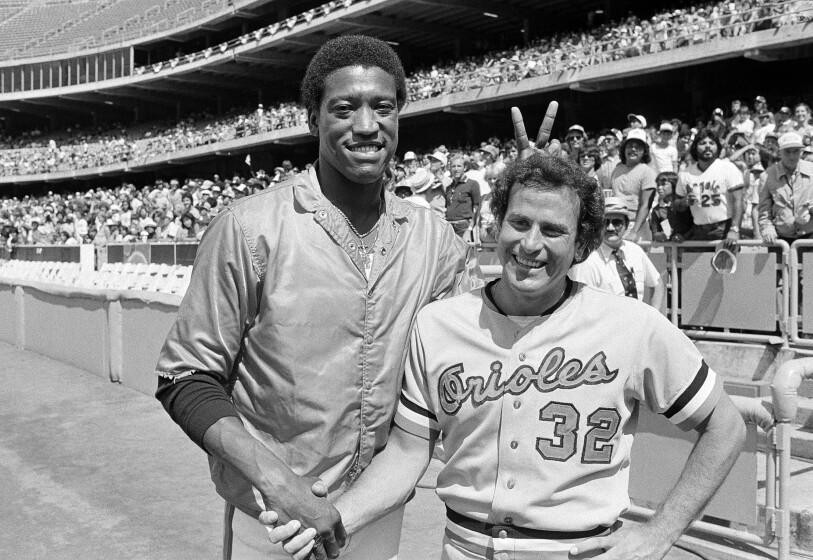

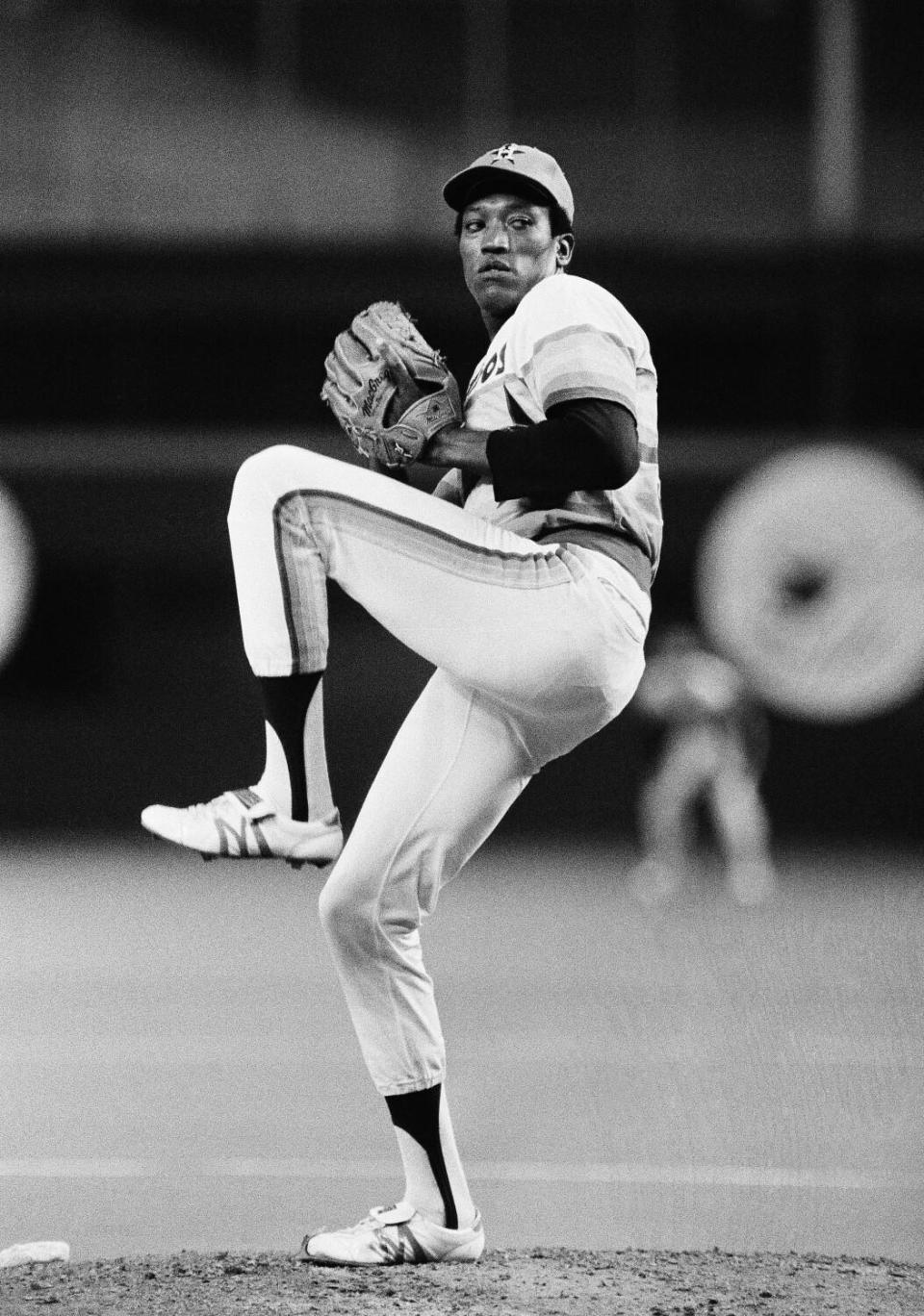

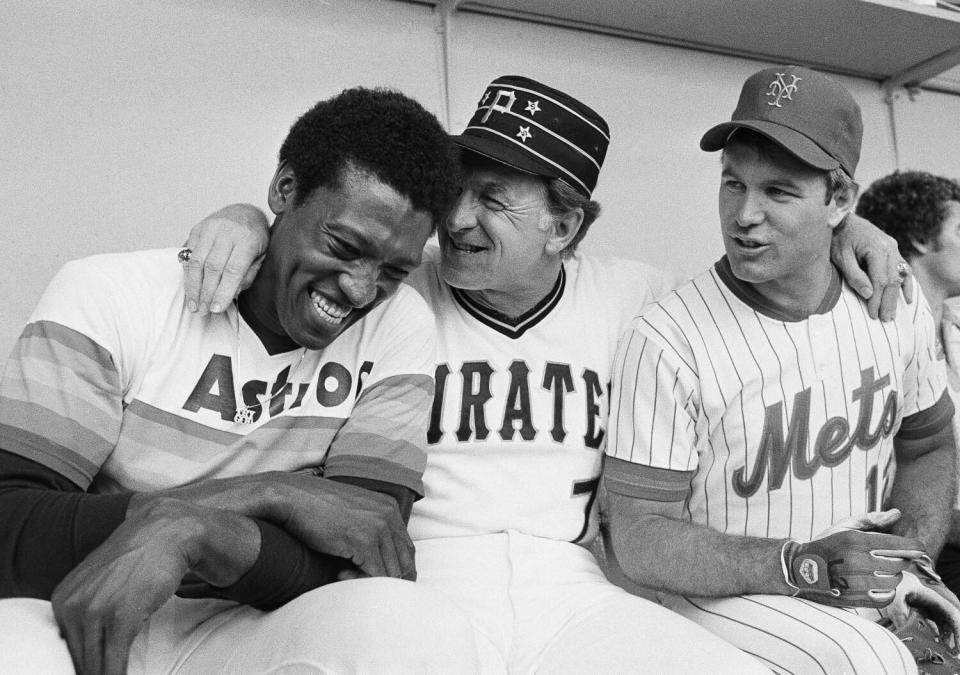

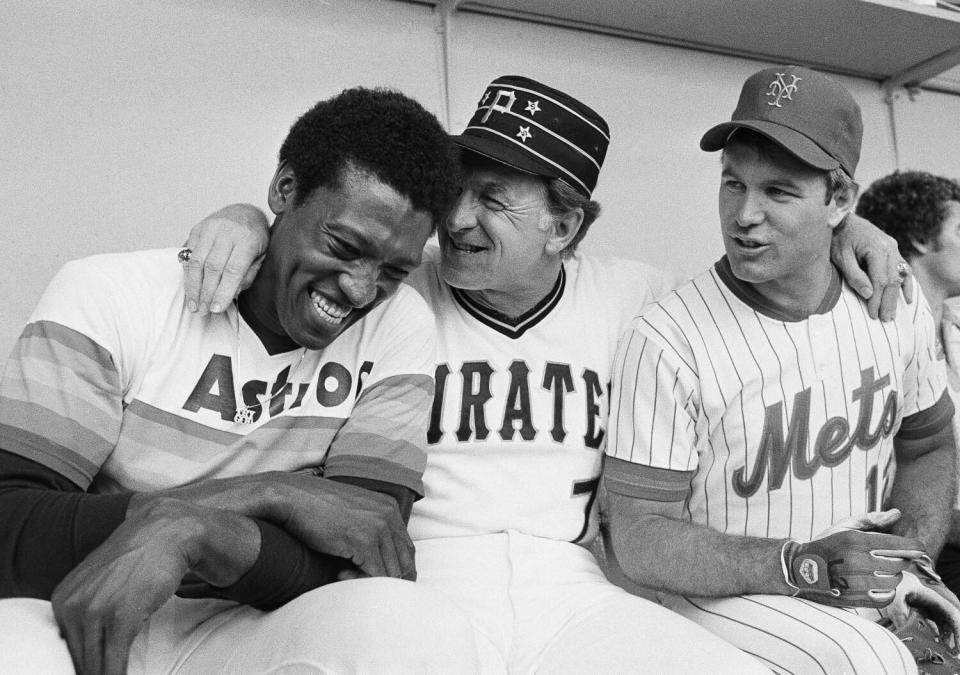

And in the middle of the idyllic setting, two men celebrated everything that they’d achieved on a square foot of rubber. The game’s starting pitchers, Baltimore’s Steve Stone and Houston’s J.R. Richard, were at the pinnacle of their profession.

Only this pinnacle, it wasn’t much of a plateau — this Tuesday in July 42 years ago, it was more of a ledge.

“If you are an aware person, if you understand this particular incarnation that we’re going through, there’s nothing promised to us. We’re here for a finite period of time,” Stone said recently. “We live the life to the best of our ability. But nobody can tell you what’s going to happen tomorrow.

“Nobody can tell you that you’re going to be the same person when you wake up.”

Both Stone and Richard were excellent that day in Los Angeles. Stone threw three perfect innings. Richard struck out three in two scoreless innings.

Neither pitched in an All-Star Game again. Stone played one more season. Richard made only one more start before his career was over.

Arm trouble derailed Stone by the next season. Richard suffered a stroke after his next start, his baseball life ripped away from him.

The blue heaven on that July day, it was only temporary.

The son of a jukebox repairman and a baseball-crazed shot-and-a-beer bar waitress, Stone’s trip to the Dodger Stadium mound was anything but conventional.

Sure, he loved pitching there — he once threw a 1-0 shutout against the Dodgers — but it was more than that.

“It was so clean, you could eat off the floors,” Stone said. “We come off the bus, walk in and head for the locker rooms and it was immaculate. The whole thing.”

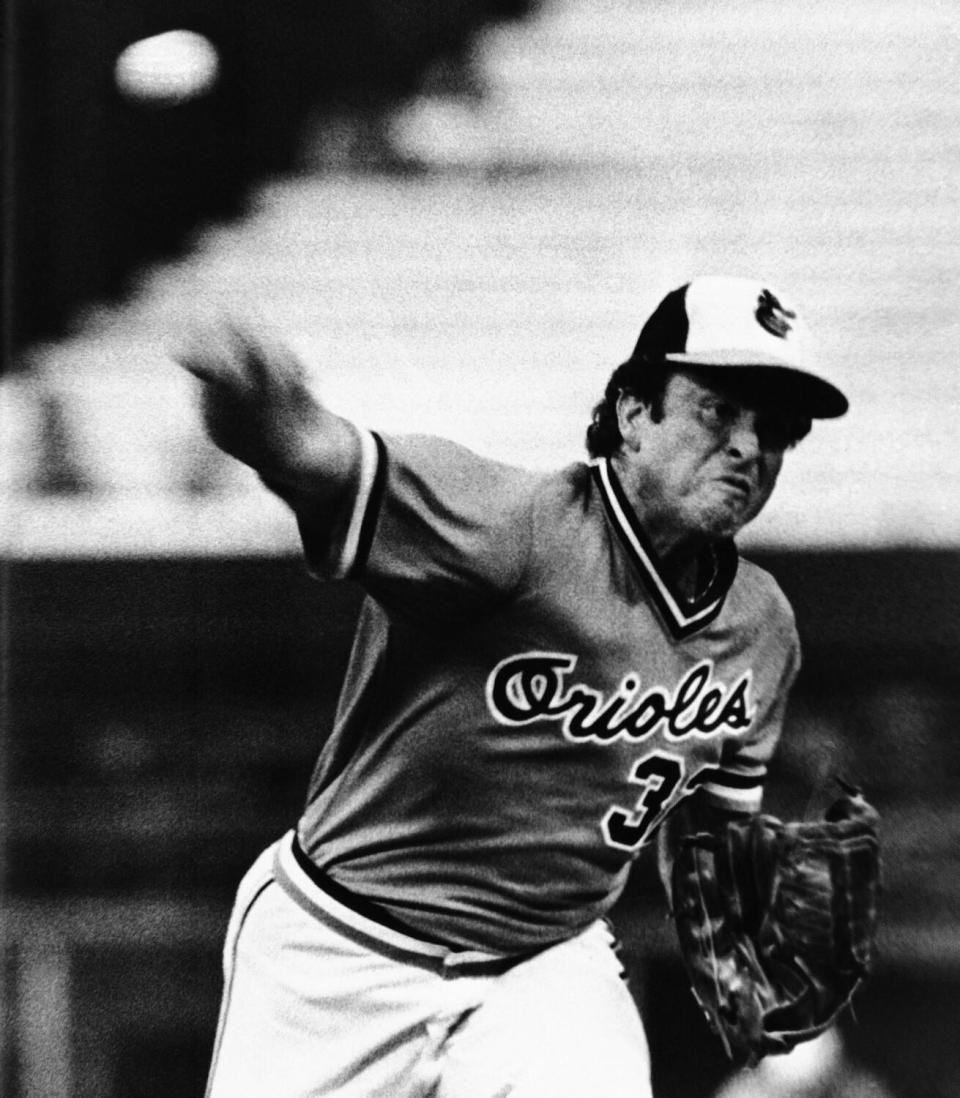

Maybe it was destined for a pitcher from Euclid, Ohio, to search out all the angles, but Stone needed a mental awakening deep into his career to go from a perfectly fine pitcher to an All-Star starter.

Midway during the 1979 season with the Orioles, Stone decided to find out the truth in the scariest possible way — dedicating all his energy into finding out how good he could be. It also meant he might have to face the reality that he was just OK.

“I had a crystal-clear illumination of how I thought I could do it. I always thought there was a better pitcher in there somewhere. And I didn’t know if I could ever get him out,” Stone said. “But I did know this new system, the mental gymnastics I was about to employ, was in the framework of my own personality. A friend said to me, ‘You’re not good enough on the field to be inconsistent off the field and expect consistency on the field.’

“… You can put five miles of dominoes in a line and all it takes is one little move of your finger, and if they’re all aligned, all five miles of dominoes will sequentially fall. I devised a system where if I did A, B, C, D, E and F, G was victory. And so I had to figure out what A, B, C and D was. And if G was victory, I’ve got to get this system, get this plan, get this consistency and then make it work.”

Stone won 12 of his first 18 starts in 1980, thinking and throwing his way through the American League as the emerging ace on the Baltimore staff.

“He didn’t try to strike you out all the time, but tried to, you know, throw you low and away and down and in and move your eyes up and down and change speeds,” Garvey said of facing Stone.

Everyone — Stone included — would agree that facing J.R. Richard was a different experience.

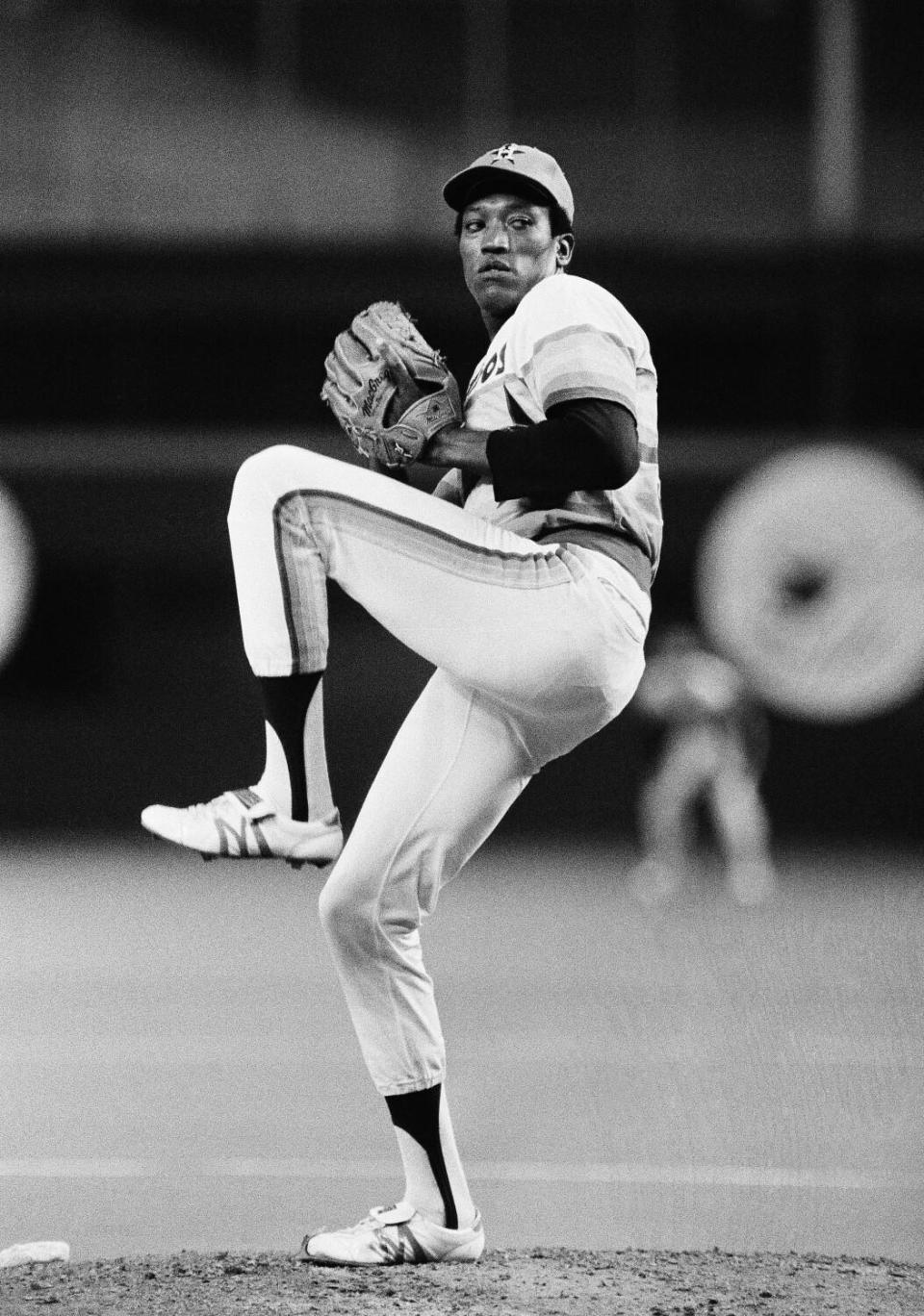

If it was a surprise that Stone was going to represent the American League at the start of the 1980 All-Star Game, Richard’s presence on the mound was an eventuality.

By the time he was a senior at his Louisiana high school, Richard was a 6-foot-8 flamethrower who didn’t give up a run all season.

He was the No. 2 pick in the 1969 draft and by his mid-20’s, he’d earned a spot in the Astros’ rotation.

“J.R., I have always said this, was probably one of the top five pitchers I ever faced,” Garvey said.

If Stone was precision, Richard was total power — a physically imposing presence who idolized Bob Gibson and fired fastballs routinely over 100 miles per hour.

Hitters in the National League, such as Garvey and Dodgers outfielder Reggie Smith, said the ball was almost impossible to see in Richard’s hands because they were so large. And once you did pick it up, it was basically already in the catcher’s mitt.

“Because he came directly over the top, it seemed like it started out about 10, 12 feet above your head. And because he was so tall and got out so far, it looked like he was handing you the ball,” Smith said. “The ball was really there so quick, you know, and it looked like a golf ball coming out of his hand because his hands were so big.”

If you were a hitter in the National League between 1976 and 1980, you knew how dominant Richard was. If you were in the American League, it was mostly just statistics combined with legend — Richard with a 2.79 ERA over a 166-start span with 1,163 strikeouts (more than one out of every five batters he faced).

The All-Star Game was a chance for everyone to see.

“You know that you’re well respected whenever people use your name to compare other people,” said Honeycutt, a longtime pitching coach for the Dodgers. “They would say, ‘I’ll never throw near as hard as J.R. Richard.’

“… I’m down in the bullpen so like I got a real up-close look. You’re just seeing, you know, the ball just being launched out of this big man’s hand. That’s just electric.”

Honeycutt couldn’t have known then, but he was one of the last to ever see it.

In the buildup to the All-Star Game, Richard said he was at his best, the peak of his pitching prowess. He had started to deal with some arm fatigue, but it hadn’t derailed him.

“I went out there thinking, ‘The game is mine,’” Richard said in his autobiography “Still Throwing Heat.” “… I was totally focused. I put on a new hat and put it on just right. I figured the opposition couldn’t touch me.”

But pregame in the locker room, Smith noticed something was a little off.

“He said that, ‘I don’t, I don’t feel well. I don’t feel that good,’” Smith said. “And his speech was a little slurred. And it was before I knew anything about the symptoms of a stroke or anything like that. And he just said he didn’t feel well … and kind of just left it at that and we can continue our conversation.

“And then he went out to pitch.”

Richard was wild, but he was effective. Stone, who was zooming along after New York Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles robbed Dodgers second baseman Davey Lopes of a hit in the first inning, would eventually face Richard.

He looked to Johnny Bench, the Cincinnati Reds catcher, and told him that all he wanted to do was to make it out of the batter’s box with all his bones intact.

“‘I’m having the best year of my career. Go out and tell that big guy don’t hit me,’” Stone told Bench. “‘I’ll get as far away from the plate as I possibly can. I’ve got no chance of hitting this ball. Just tell him not to hit me.’”

Stone struck out, a foot in the dugout even before the ball popped into Bench’s glove.

He’d later learn the pitch was 103 mph.

It was the only blemish on Stone’s day as he expertly hit spots in and around the strike zone.

“Steve went three innings just like it was nothing,” Honeycutt said.

His parents were in the stands as he was perfect, nine batters faced, nine retired. It’s a mark that will almost certainly stand with All-Star pitchers now working a far lighter load.

After Stone struck out Dodgers pitcher Bob Welch to end his day, he walked off the field, his emotions rising up and out in the form of a freeway-wide smile that the cameras caught before he ducked into the dugout.

“You’ll see me look up in the stands, to locate them,” Stone said of his parents. “That was just great. That was it. When I look back at the recollections and I look at the tape of it, the smile on my face after locating them — that’s how I felt.

“That’s what it meant to me.”

In his first start after the All-Star Game, Richard didn’t feel like himself even though he was getting batters out. In the fourth inning, his vision blurred so badly he couldn’t pick up his catcher’s signals.

He went on the disabled list and doctors discovered a blood clot in his arm, though it wasn’t serious enough to shut him down.

Two weeks later with the Astros out of town, Richard played a game of catch inside an empty Astrodome.

“All of a sudden, I felt a high-pitched tone ringing in my left ear. And then I threw a couple of more pitches and became nauseated,” Richard said in “Still Throwing Heat.” “A few minutes later, then the feelings got so bad I was losing my equilibrium. I went down on the AstroTurf. I had a headache, some confusion in my mind, and I felt weakness in my body. I didn’t have knowledge of anything that was going on.”

It was a stroke. Scans confirmed that he had actually suffered three of them.

“I was still alive. I thought that whatever it was that was wrong with me, even after the stroke, if I gave it enough time — I didn’t care what it was — I would get better,” Richard said in his autobiography. “What I hated hearing was that I wouldn’t be able to pitch anymore. I felt awful about that.”

And despite a handful of comeback attempts, Richard never returned to the majors. His troubles, though, were far from over.

He suffered from depression, ran out of money amid failed marriages and, eventually, found himself living underneath an overpass in Houston before he began to bounce back.

Tragedy, though, didn’t stay far away for long. Richard died from complications of COVID-19 last August. He was 71.

Stone’s 1980 continued to be magical as he finished 25-7. He won the American League Cy Young Award, his transformation into a physically and mentally dominant pitcher complete.

Following one more season, Stone was forced into retirement because of arm problems.

He appeared in that one All-Star Game. “It’s not that it was easy. It’s that it was easier for them. They were great,” Stone said of the multitime All-Stars of his era. “They belonged there. That was their home. I wasn’t great. I borrowed greatness. I knew I’d have to give it back. But I borrowed it.”

Even before Stone, now 74 and the color analyst for the Chicago White Sox, or Richard threw a pitch on that postcard July day, this All-Star Game — won by the National League 4-2 — was about perspective.

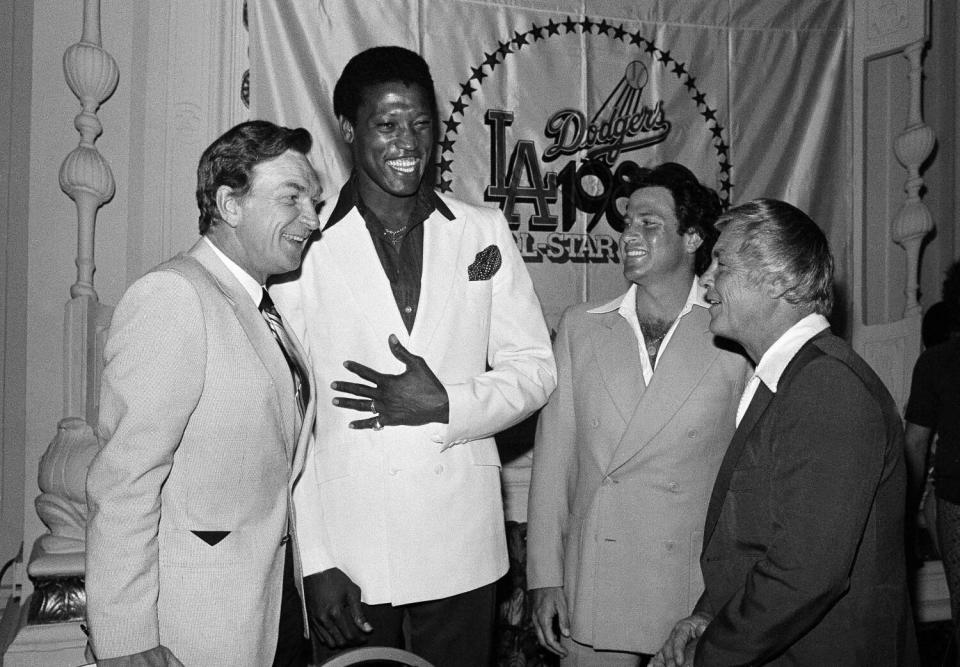

As part of the All-Star festivities, players gathered in a room for a luncheon where that message got hammered home by Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully.

The gist was this: Today you’re an All-Star. Savor it. Soon enough, you’ll be an old-timer.

The message has stuck with Stone for the last 42 years.

“You absorb it at the time, but I was young enough, good enough and strong enough … , ” he said. “But you think back to it and he couldn’t have been more right if he told me the sun was going to rise in the East tomorrow.”

[embedded content]

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.