If the New York Yankees have a superpower, it’s — well, it’s probably shooting money out of their limbs like Spiderman with webs. But if they have an on-the-field superpower, it’s conjuring excellent bullpens virtually every year.

Relievers are famously flighty, even the best ones have taken contenders on roller-coaster rides as their effectiveness fluctuates wildly from year to year or even sometimes month to month. The Yankees aren’t immune to that on an individual level, but under GM Brian Cashman they have persistently managed to tilt the game in their favor in the late innings.

Coming into 2022, the Yankees’ tightly held favorite status in the AL East was widely questioned. The Toronto Blue Jays are young, bold and rising. The offseason was technocratic and a bit underwhelming by Bronx standards. Many observers (sheepishly raises hand) didn’t think the Yankees had done enough to stay ahead of Toronto.

In a little over a month, they have seized control of the division, thundering to a 28-10 start, dominating the Blue Jays in head-to-head matchups. They have turned an opening day coin flip into 76.2% odds of winning the division and similarly strong odds of earning a bye in MLB’s expanded postseason format.

The biggest reason — literally and figuratively — is Aaron Judge, who is turning in an MVP-caliber contract year thus far. But a huge chunk of the credit must also go to a difference-making bullpen that has towered over the Blue Jays, and indeed the rest of the league.

Yankees relievers lead MLB in ERA, park-adjusted ERA, win probability added and, incredibly, homers allowed per nine innings.

That’s particularly notable because Aroldis Chapman, the high-powered closer, is laboring through exactly the type of turbulence that might torpedo some teams’ seasons. And because Zack Britton, the other big name on the staff, is on the shelf after Tommy John surgery. But no rival has surged through that apparent opening. Instead, what’s shining through is that Yankees superpower: A mastery of pitching evaluation and development that has molded new stars in the form of Michael King and Clay Holmes.

A King is developed, not born

You’ve heard that baseball is a game of failure. Usually, that reference nods at the fact that the very best hitters in the game make an out 60% of the time. If you really want to gaze into the abyss, though, allow me to direct your attention to the world of pitching prospects.

Prior to the 2019 season, seven of the Yankees’ 10 best prospects, as rated by Baseball Prospectus, were pitchers. Where the dream for virtually every young arm is a rotation stalwart, the Yankees have gotten precisely one (not very good) start from that group in 2022. The pitcher who made that start, Luis Gil, was sent back to Triple-A and left a game this week pointing to his elbow. Hope is hard to maintain on the mound. One was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for starter Jameson Taillon. And three of them have become bullpen contributors.

The No. 7 prospect on that list was King. Back then, he was a right-hander picked up in a deal you don’t remember with the Miami Marlins whose calling card was a good sinker that went 91 to 93 mph. There were no good secondary pitches to speak of, and the best-case scenario was “innings eater.”

In some ways, he has come up short of even that. The handful of starts he made at the big-league level were rocky, and the Yankees don’t have much space for fledgling back-end arms that other teams might tolerate. Of course, that’s a needlessly limited way of viewing things. In the only way that matters to the always competing Yankees, he is a rollicking success.

His route to relief ace is an exemplar of how the organization squeezes lemonade out of these situations and keeps its bullpen stocked with world-beaters.

Remember that good but not overwhelming low-90s sinker? It goes 95 mph now (on average!) and is complemented by one impossible offspeed weapon against righties and another against lefties.

After dropping off the starter’s path, King took on a multi-inning relief role. Across the 25 2/3 innings he’s thrown this year (instead of a typical starter’s 40), he’s posting a 1.40 ERA with a closer-esque 39.4% strikeout rate.

On a rate basis, he’s been as effective as any pitcher in the world. And because he’s carrying the Yankees through multiple frames at a time, King has been one of the 16 most valuable hurlers in baseball thus far by either major WAR calculation.

The most impactful of those new pitches is the breaking ball he learned from Corey Kluber last year. It falls into the ascendant sweeper category, and it’s a very good one.

Because of the relatively low arm angle that creates his tailing sinker, King has proven particularly adept at generating bedeviling sideways sweep. A lot of hitters start their swings thinking it will dot the outside corner, then just about throw their arms out of socket trying (and failing) to reach it.

Deployed predominantly against right-handed hitters, the pitch has resulted in whiffs on 47.1% of swings and surrendered a grand total of three hits, all singles. Against lefties, he turns to a four-seam fastball more often and swaps in a Wiffle ball changeup that hitters flail on 77.8% of the time, and haven’t mustered a hit against yet.

This is the type of double-take inducing progress that seems to routinely emerge from the Yankees’ minor-league system. Building velocity is a regular occurrence, and versions of the homer-suppressing, sideways-sliding offspeed offerings like the sweeper and changeup King uses have also become trademarks.

Even when durability or command or some other limitation blocks a promising arm from grabbing a rotation spot, the Yankees help them formulate a plan to dominate over an inning or three.

A masterpiece ready to be sculpted

A team that builds so many vicious repertoires is also attuned to potential unfulfilled on other teams. So it probably should have raised red flags for the Pirates front office when New York came calling about a 6-foot-5 right-hander with a 5.57 career ERA in 91 games.

Alas, they answered the phone and sent him packing for two minor-league infielders. Clay Holmes donned pinstripes shortly before the trade deadline in 2021 and became a different pitcher on a dime.

In 48 1/3 innings since the deal, he has tallied a 1.12 ERA and cut his WHIP almost in half. A pitcher who battled walks throughout parts of four seasons in Pittsburgh — he had 25 just in the first half of 2021 — has issued only six free passes with the Yankees.

What the Yankees identified, and helped Holmes implement, feels elementary in retrospect.

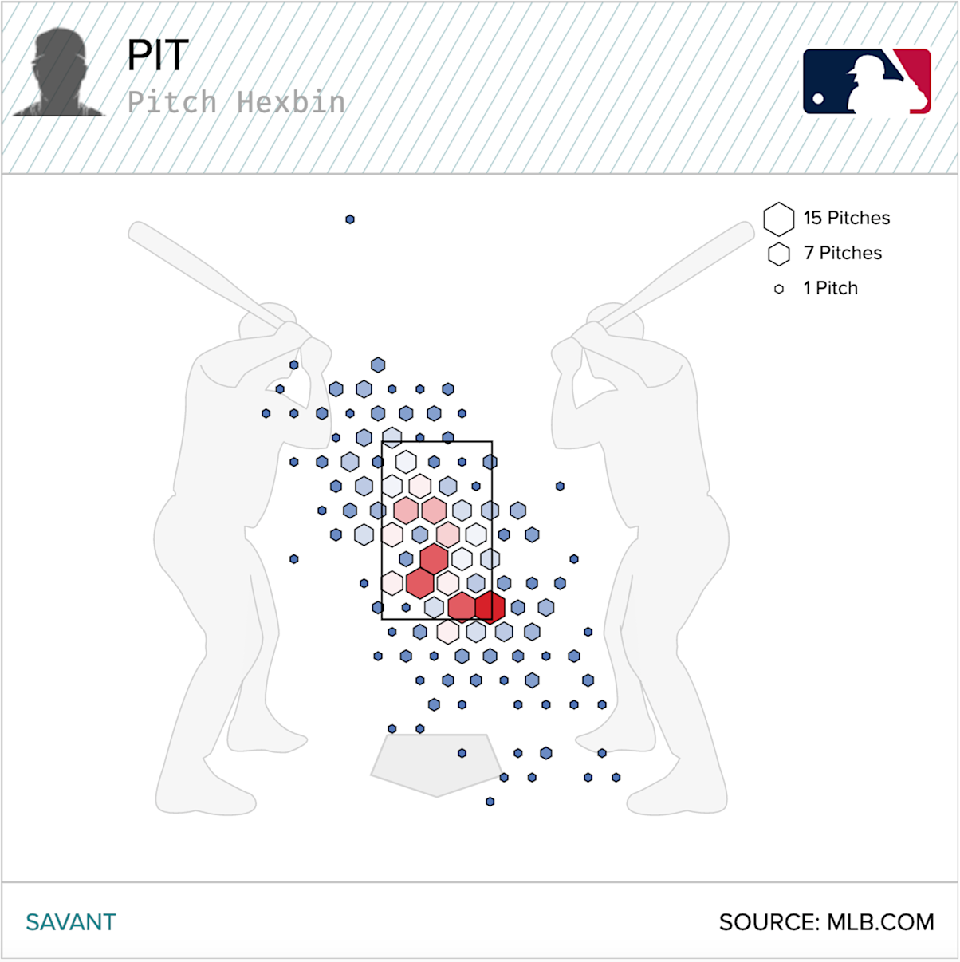

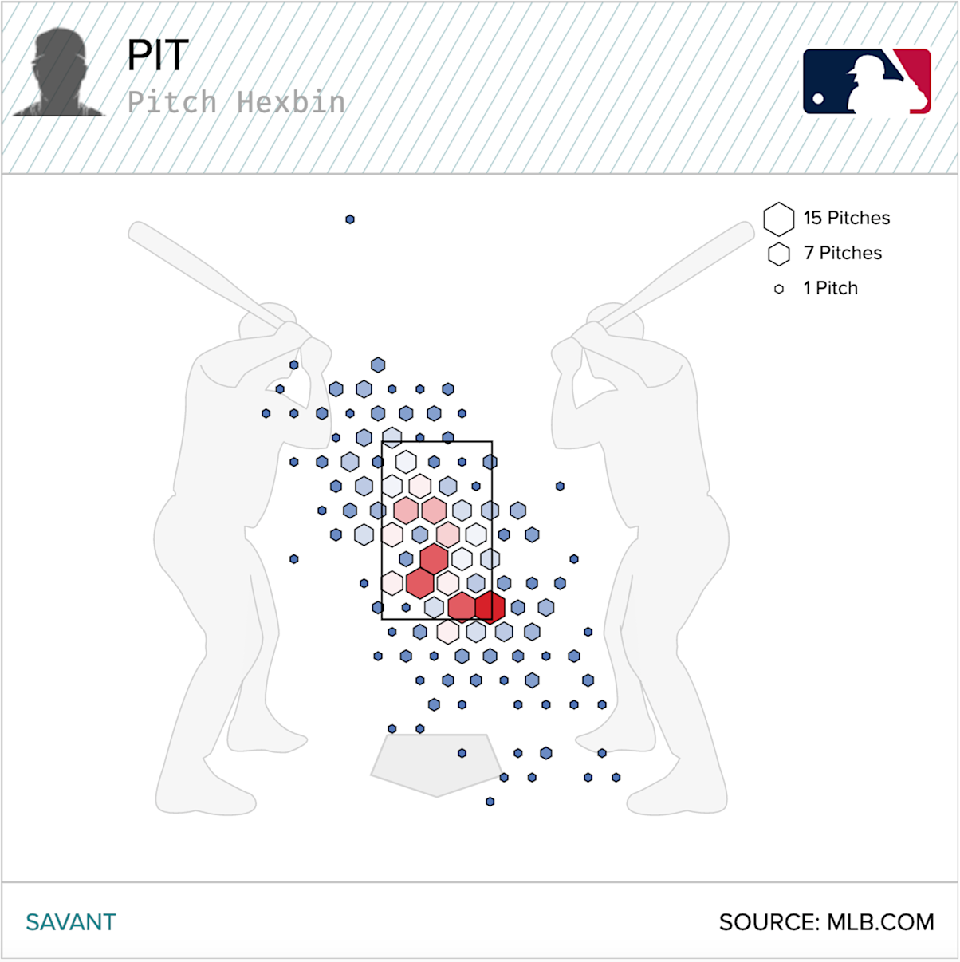

You ready for this scorching insight? They noticed that his turbo sinker — which looks like this …

Even this week, with fans clamoring for Holmes to ascend to the closer role as the veteran fireballer Chapman struggles with control, manager Aaron Boone had a one line answer to a reporter who asked why that sinker so good.

“Have you seen it?”

It’s the same sort of mid-to-upper 90s swerving bowling ball that relievers like Blake Treinen have made careers out of. And Holmes was mixing it in with at least two inferior pitches, including a blah four-seam fastball, and often missing low when he did throw it.

Now, to grant the Pirates and every other team some credit, a scout who spoke to the New York Daily News admitted they didn’t see this glow-up coming either. The potential of that pitch was obscured by its usage.

Holmes realized the sinker was his bread and butter, but the Yankees encouraged him to fully lean into it.

“I knew my sinker was my better fastball. So it’s hard to really come out of the bullpen and you are only seeing a guy one time and you don’t want to get beat on something that’s not your best pitch,” Holmes told the Daily News. “So that was kind of my thought process behind that.”

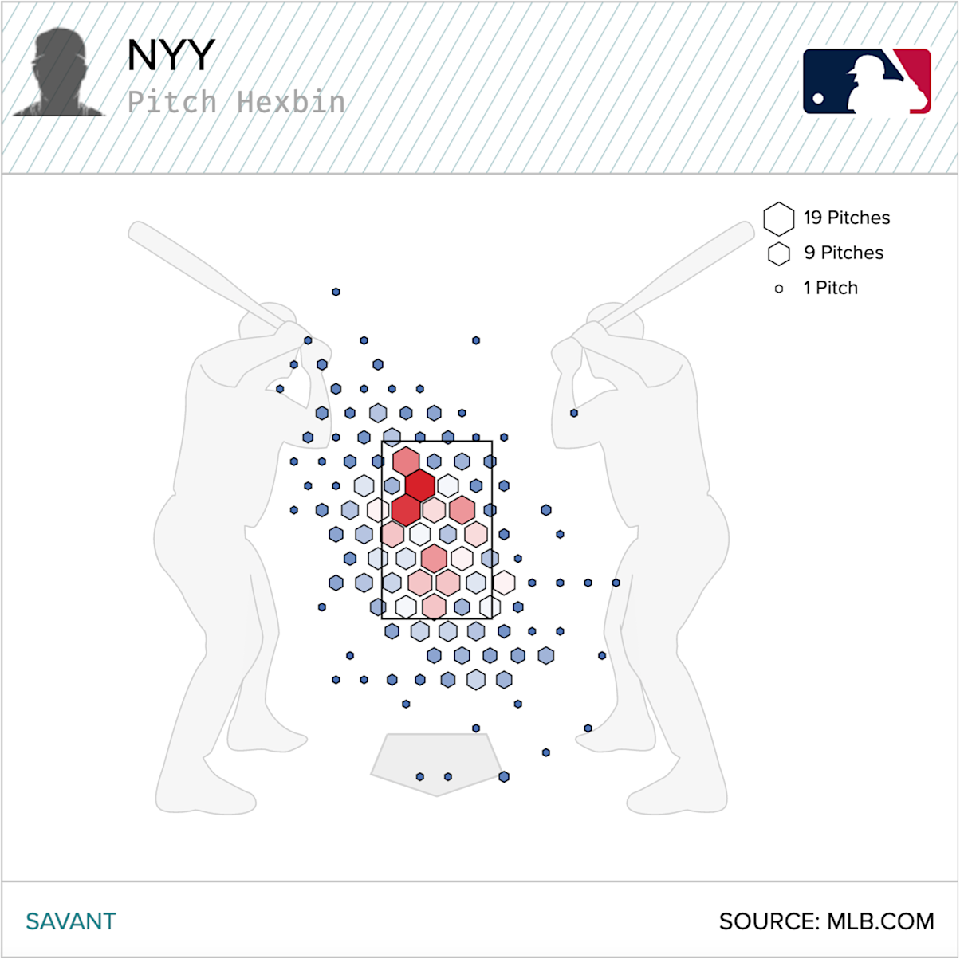

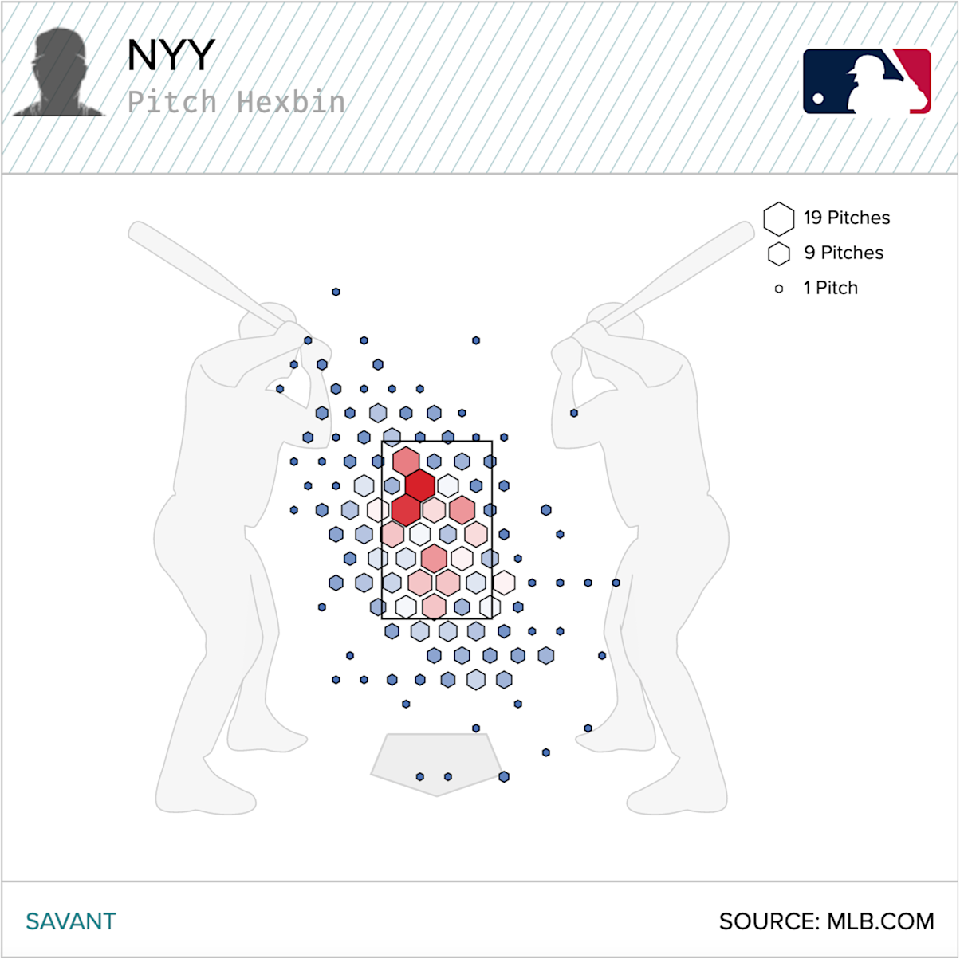

He threw the sinker on 51% of his pitches with the Pirates. With the Yankees, he has fired it 76% of the time. They also used it to solve his walk problem. The pitch is so good, it doesn’t need to be finessed into certain parts of the zone. It is the rare fastball good enough to miss bats. In Pittsburgh, he was underestimating the pitch by trying to finesse it into a narrow window.

In the Bronx, Holmes just powers it down the middle, even up in the zone. It gives him a wider margin of error on location and, spoiler alert, hitters can’t square it up anyway.

For now, there’s no publicly acknowledged changing of the guard in the ninth inning, but the official designations are beside the point. Holmes has grabbed three saves and demands consideration for the most crucial moments. If Chapman continues to falter, he’s an otherworldly backup plan. If Chapman regains his form, the Yankees have a multi-headed monster laying in wait every single game.

When we were scouring the AL East contenders for an edge this spring, the shiny new toys in Toronto understandably caught our eye — they’re still formidable and could surge into a serious battle with this Yankees squad. But what some of us missed was not new at all, but a pattern repeating itself.

Like Dellin Betances and Chad Green and David Robertson and others before them, the Yankees have aces in the hole. Relief aces. And we should all be expecting it by now.