Editor’s note: This story was originally published in 2021. After an eight-year battle with the NBA, Dropping Dimes convinced the league at the end of 2022 to give recognition payments to former ABA players.

INDIANAPOLIS — George Carter was a limo driver in Las Vegas. He enjoyed a beer after a long day of work and it was even better if there was a game on at the bar. On the good days, he was funny and easygoing. The things that annoyed other people, Carter let roll right off his back.

Carter was 75 and on the bad days, he was hardened and tough. He had throat cancer. He was being evicted by his landlord, unable to afford the new rent, medical bills piling up. Not able to drive because of chemotherapy.

George Carter was an out-of-work limo driver living in Nevada when he died penniless in November. No family to be found, not even a long lost cousin, and literally only one friend on this earth.

***

The box of fan mail was tucked away in a spare room, lost among other boxes of old clothes and throw-away trinkets.

Mr. Carter, You were my hero. George, You were one of the best to ever play. Dear George, Can I please have your autograph? I watched you in the 70s. You scored 38 points one night and 32 the next.

The Hall of Fame memorabilia was in that room, too. Relics from the days Carter was a superstar of the American Basketball Association.

“He was really something — and he never talked about it,” said Jennifer Stauffer, Carter’s friend and a fellow limo driver he met in 1999. “I knew he had played. But I didn’t know…”

She didn’t know just how incredible he was.

A pauper’s funeral

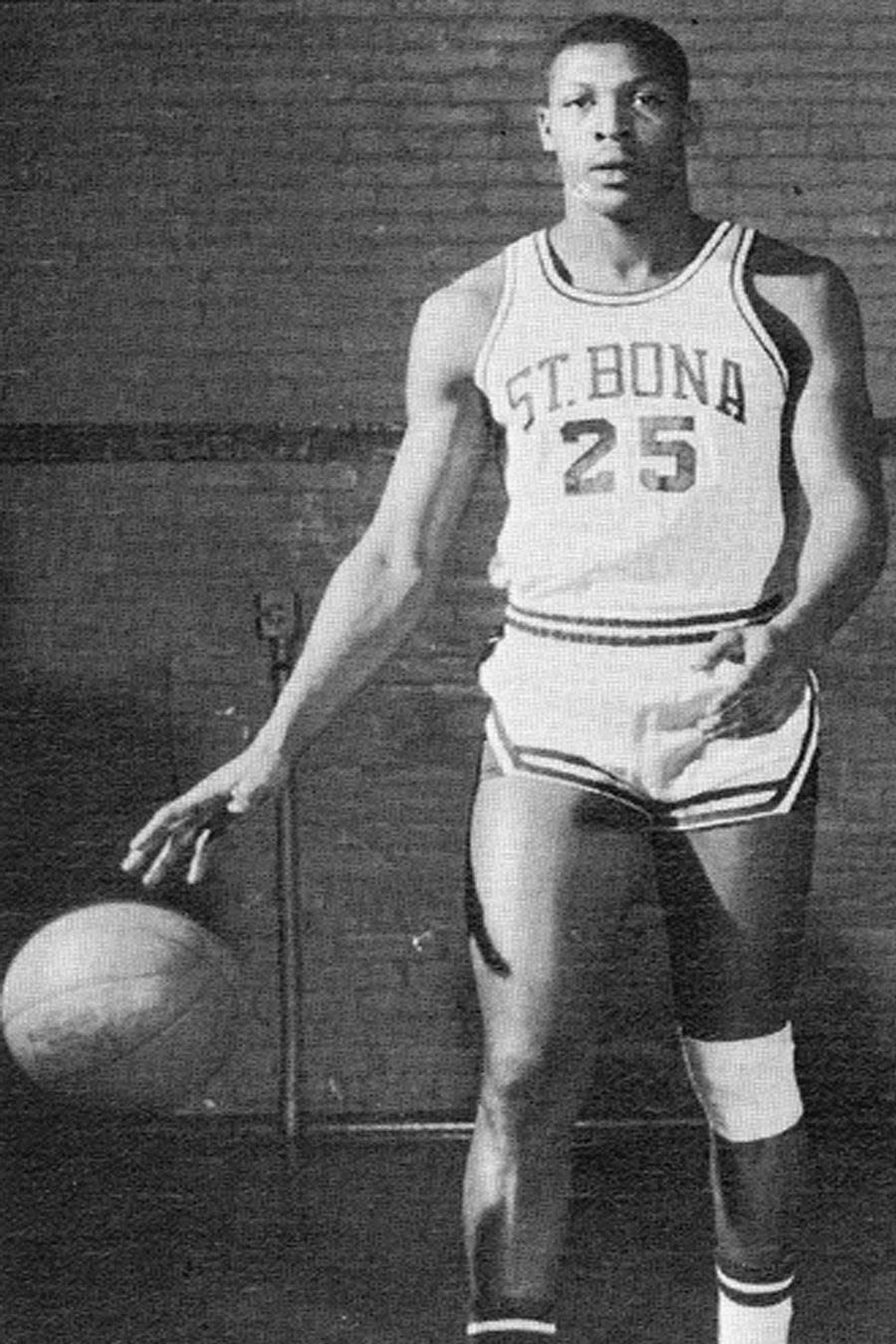

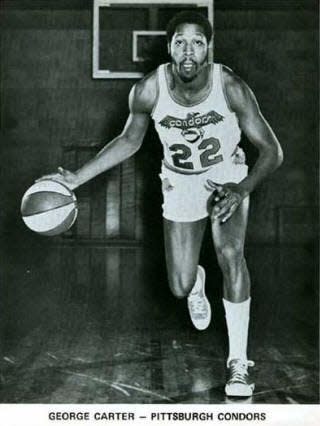

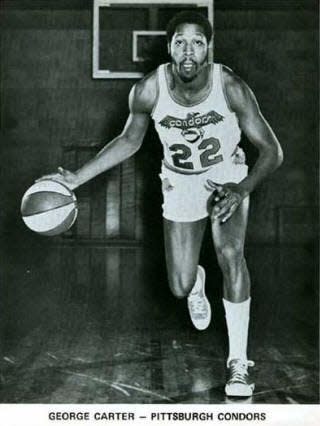

Carter was a brilliant athlete. When he graduated from St. Bonaventure University in 1967 — with 1,322 points and averaging 19.4 points per game in three seasons — he was picked 81st overall by the Detroit Pistons in the NBA Draft.

He also was drafted by the NFL’s Buffalo Bills and the MLB’s New York Mets. Three professional sports teams wanted Carter to play for them.

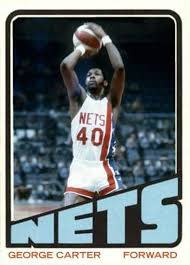

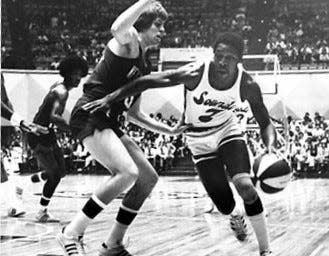

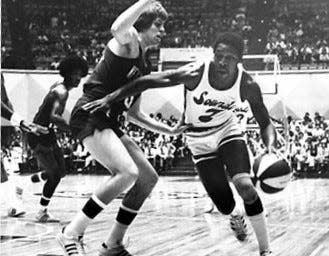

Instead, he served two years in the military before going to play with the ABA’s Washington Capitals, where he was an all-star in 1970. He went on to the Virginia Squires, playing alongside Julius Erving; then to the Pittsburgh Condors, Carolina Cougars and New York Nets.

During his professional basketball career from 1967 to 1976, Carter averaged more than 18 points and nearly 7 rebounds per game. When he retired, he finished with more than 8,000 career points.

Yet, the end to Carter’s life was heart-wrenching. When he died, there was no family, no means to have a funeral. His remains were to be cremated and he would be buried in a grave with no marker.

No one would know that here lay a man who at one time lived a life of greatness, a man of remarkable athletic prowess, a sports hero.

Until Stauffer and Indianapolis-based Dropping Dimes Foundation, whose mission is to give back to former ABA players and personnel experiencing financial or medical difficulties, stepped in — and made something incredible happen.

‘I wonder if they can help me?’

At the end, Stauffer said, Carter was paranoid. “But I don’t want to remember him that way.”

For the past 20 years, Carter had been her sidekick. Her friend. If she needed someone to cover her limo riders, she called Carter. When he needed someone to cover his, he called Stauffer.

But as Carter became sicker and was worried about his health and financial security, he could be bitter.

Carter had received a letter several years ago from Dropping Dimes. The letter asked if he needed assistance or if he knew anyone from his ABA days who did. Carter didn’t need help then, but he held onto that letter.

As the devastation of being evicted from his home of 15 years set in at the end of 2019, along with the cancer, Carter turned to Stauffer one day.

“He said, ‘I wonder if they can help me?'” Stauffer said. “I said, ‘Well George, we will find out.'”

With Stauffer’s help, Carter drafted a letter to Dropping Dimes. “It was a troubled note I would call it,” said Scott Tarter, co-founder of the organization.

“My savings are dwindling quickly and I am worried for my future situation,” Carter wrote. “I looked into affordable housing and was told there are 900 people on the waiting list. Please, if there is any way you could help me stay in my home of 15 years, I would be so grateful. I can’t even afford to move, really.”

When Tarter called Carter the first time, the phone conversation wasn’t pleasant.

“He was just very bitter and angry,” Tarter said. “His basic position was ‘Who the hell are you? I’ve heard people say they were going to help me. I’ve been played before.'”

Dropping Dimes started paying some of Carter’s medical bills and secured a law firm in Las Vegas to deal with his eviction. That bought them eight months. Dropping Dimes found him a senior living community, made his down payment and helped with rent.

Tarter’s phone rang. Carter was on the other line and he wanted to talk basketball. He was laughing. The two became friends.

‘It was a beautiful period’

For four wonderful months, from August, when Carter got into his new home until November, when he died, it was a “beautiful period,” said Tarter. Carter became a different person.

“He was just the nicest guy. He had a really raspy, rough voice,” he said. “We talked about all kinds of neat things.”

Stauffer, Carter’s emergency contact, got the call on Nov. 18. Carter had died at 76 in the hospital. She was trying to get off work to see him that day when doctors called to tell her they were giving him pain medication and antibiotics to keep him comfortable.

She didn’t make it.

That night, she went to Carter’s home to get his fan mail and memorabilia to donate to Dropping Dimes. She knew if she didn’t, the state would swoop in to clear it out.

“And what, are they just gong to auction this off? And nobody is really going to know who he was?” Stauffer said.

While in his house, she saw a letter she hadn’t before. Someone had written Carter asking him to autograph a photo, and had sent a $15 check. Carter never cashed the check. The photo was gone.

The letter was from just a couple years ago when Carter could have used that money.

It brought Stauffer to tears. It was all so sad.

And then, the funeral home called her. Stauffer had no idea what she would do with his body.

An emotional memoriam

The only place she knew to turn to was Dropping Dimes. They had been so amazing at helping Carter before.

Tarter and his organization called the funeral home in Las Vegas and learned that Carter would be given the most basic of burials. Instead, Dropping Dimes signed a contract to take responsibility for Carter’s body. The funeral home waited 30 days to make sure no one claimed him. No one did.

“Honestly, I was frustrated and angry at the time that he was going through that,” said Tarter, whose organization is working with the NBA to try to get the league to give ABA players a modest pension. So far, that hasn’t happened.

“I can’t for the life of me understand why the NBA or NBA players association doesn’t take care of these guys, business-wise, pro basketball-wise, history-wise and humane caring-wise,” he said. “It doesn’t make sense.”

Tarter wrote an emotional memoriam to Carter and posted it online.

“He mattered. His life mattered,” Tarter said. “And here he is. Nobody claiming him, nobody caring about him.”

Soon after that missive, St. Bonaventure called Dropping Dimes. Jim Baron, a former hall of fame coach and player at the university, had learned of Carter’s death.

There is a beautiful cemetery just across the street from campus. With Dropping Dimes’ help and funds raised by the college’s alumni association, Carter will be buried there by the school where he still today is one of the best players to ever take the court.

“We just felt like it was the right thing to do,” said Tom Missel, chief communications officer at the university. “It’s heartbreaking when you have someone who had such a storied legacy to fall on hard times at the end of life.”

A proper headstone will be put up, too, at his burial site.

George Carter will not be forgotten.

Trying to make it through life

If Carter had played out his career in the NBA, things likely would have been different for him, said Tarter.

“For some reason, the ABA slipped through the cracks during the merger,” he said of the 1976 NBA/ABA merger.

Most of the ABA teams “just died,” Tarter said. “The players’ pensions, health benefits, contracts just ended and those guys were just left hanging.”

Dropping Dimes has done sophisticated calculations. If the NBA agreed to help the 105 ABA players who qualify, meaning they were in the league at least three years, with the minimum $400 a month, it would cost the NBA $1.8 million a year.

The remaining players range in age from 68 to 84. The average male life expectancy is early 70s.

“These guys are dying very quickly and they are not going to be around much longer,” Tarter said. “It’s not a callous thing to say. It’s important to recognize. That $1.8 million? The NBA won’t even need to fund 10 years from now.”

Tarter said Dropping Dimes is in discussions now with the NBA about the plight of former ABA players like Carter.

“Those talks are taking place at a high level and the NBA has indicated it’s interested in addressing the problem,” he said.

Tarter is hopeful the NBA will take action soon, perhaps agreeing to pay players a modest pension.

That money, after all, would have helped Carter, who died alone in a hospital, who died with one friend and no family and living in a place that he couldn’t call home. He had just moved in.

His cremated remains are being brought this week to Buffalo, where he will be buried at St. Bonaventure in the spring.

Carter never got to know he would be laid to rest near the campus where he was a basketball star. Stauffer often wonders if he worried about his funeral or what would happen after he died. Probably not, she said.

That was the least of his worries.

“He was just trying to make it through life,” she said, “to live.”

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: The tragic ending to ABA superstar George Carter’s life: ‘He mattered’