The stylistic shift that helped transform Gonzaga from perennial contender into upset-proof machine wasn’t necessarily designed to deflate inferior opponents — but on Saturday night in Portland, that’s exactly what it did.

It exhausted ninth-seeded Memphis, who once led by 12 in the second half of a second-round NCAA men’s tournament game.

It weighed down legs, and hastened breathing, and dragged weary hands to knees as the Zags roared back to victory.

“That’s something that meant a lot to the guys,” Gonzaga strength and conditioning coach Travis Knight said of Memphis’ fatigue.

Because the gassed opponents left in their wake had been overwhelmed by a relatively newfound tenet of Gonzaga basketball.

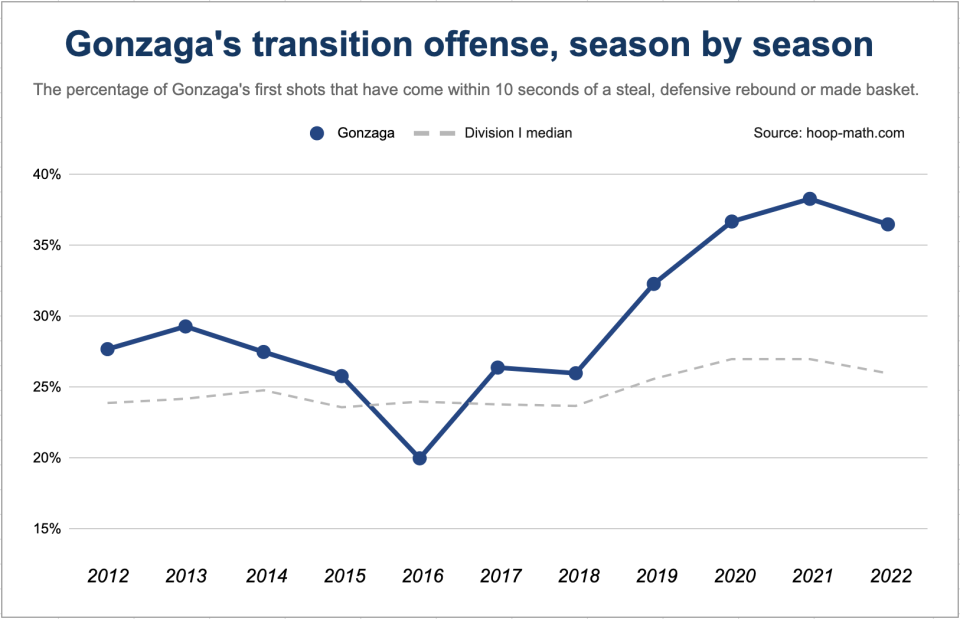

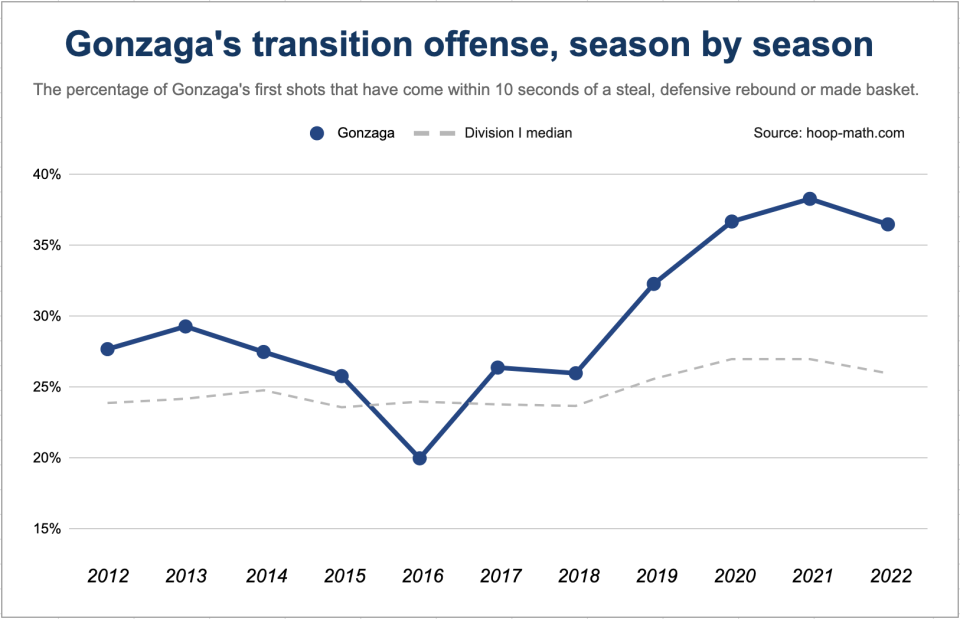

The Zags spent most of last decade playing at an unremarkable, slightly above-average pace. They won plenty at this pace, and nearly won a national championship. Then, in late 2018, they started to run at breakneck speed. Over the past four seasons, the most successful stretch in program history, they’ve played faster on offense than anybody else in Division I.

Their tempo-pushing enables blink-of-an-eye comebacks, and has shielded them from upsets en route to seven straight Sweet 16s. It isn’t the only reason they’ve romped through early rounds, of course — elite recruits and a Hall of Fame coach are the primary ones. But it helps.

Gonzaga, in a way, has become the anti-Virginia. It need not break from style when facing a deficit. It need not panic when first halves go awry. Its margin for error is vast.

Its games feature roughly 148 possessions. The Zags have, on average, 28 more opportunities per night than Tony Bennett’s best Virginia teams had to exert their superiority. And they often do just that. They haven’t lost to a non-top-25 team in three years. They’re essentially living out an old Roy Williams axiom: “If I’m better than you are, the more possessions we play, the more likely it is that I’m going to beat you.”

There is anecdotal evidence of a widely assumed relationship between pace and March Madness upsets. A FiveThirtyEight analysis “found that, among teams that were expected to win the most [NCAA men’s tournament] games, those that played at a slow pace tended to underachieve, while those that played faster were most likely to outperform their expected win totals.”

Their invulnerability, though, is “a side effect” of their tempo, not a reason for it, Gonzaga assistant coach Brian Michaelson said in a phone interview as he prepared for Thursday’s Sweet 16 showdown with Arkansas (Gonzaga -9.5).

“We play this way,” he explained, “because it’s fun, because we, as a staff, think this is how the game is meant to be played.”

When Gonzaga made its ‘drastic shift’

There was no single conversation that spawned Gonzaga’s evolution from fast to turbo-charged, no epiphany that inspired head coach Mark Few to mash the accelerator. The shift was merely a product of Few’s career-long preference for uptempo basketball and his knack for adapting his style of play to fit his personnel.

When Few joined Dan Fitzgerald’s coaching staff in 1990, Gonzaga was a seldom-relevant program saddled with a remote location, frigid weather, antiquated facilities and a name that was difficult to pronounce. In those days, Fitzgerald instructed his assistants not to bother wasting precious time or money pursuing recruits with Pac-10 scholarship offers who surely wouldn’t come to Gonzaga.

Three decades later, Few and his staff have turned Gonzaga into a destination for top overseas prospects, elite transfers and even McDonald’s All-Americans. He landed his first in 2016, and more have followed.

The influx of talent opened new possibilities. As Michaelson puts it, “Our personnel on one hand forced us to, and on one hand allowed us to really play super fast.”

While Few’s teams had often seized chances to attack in transition, Gonzaga’s 2018-19 roster was built to fly. Senior point guard Josh Perkins thrived making split-second decisions at full speed. Wings Zach Norvell and Corey Kispert were both lethal in transition. And the real difference makers were mobile, athletic forwards Rui Hachimura and Brandon Clarke, both of whom could grab a defensive rebound and lead a break themselves, or beat their man downcourt and finish one.

“That’s the year I really think there was a drastic shift,” Michaelson said.

“And the team now,” said Jeremy Jones, a senior forward that year, “is doing it on another level.”

In 2018-19, a 33-win Gonzaga team averaged 14.7 seconds per offensive possession, the sixth-fastest in the nation, per KenPom. The next year, with four new starters, the Zags were still men’s basketball’s seventh-fastest offense. In 2020-21, with four guards surrounding Drew Timme, Gonzaga revved up to 14.4 seconds per possession, the third-fastest. This year, with slender 7-foot freshman Chet Holmgren alongside Timme in the frontcourt, the Zags are second only to St. John’s at 14.6.

Over the past two seasons, they’ve taken more than 37% of their initial shots in transition — and made them at an unparalleled clip. In each of the past four years, they’ve boasted the nation’s most efficient offense. They’ve accelerated without compromising ball security or shot selection.

And their secret, coaches and former players say, is exactly the opposite of what you’d expect.

Basketball > old-school conditioning

Gonzaga’s strength coach can’t remember the last time he asked a player to dash up a hill, to run a six-minute mile or to complete a set of sprints.

In fact, Knight says, “We’ve actually gotten to the point where, except in very isolated, individualized situations, we don’t do any formal conditioning.”

Instead, Gonzaga players prepare to play faster than anyone else in college basketball by practicing faster than anyone else in college basketball. That means 5-on-5 scrimmages on “Competition Mondays” happen at high speed. So do other full-court drills that All-American Corey Kispert “hated.” There are hardly any interruptions to correct mistakes, hardly any stoppages to micromanage.

The teaching comes away from the court, in the film room. Coaches might show players clips to demonstrate when they made a bad decision with the ball, ran to the wrong spot on the floor or didn’t sprint aggressively enough.

“Everything we do here is built to play fast,” Michaelson said. “Teams say they want to play fast, and then they hold up play cards. There’s no chance. They’re reading a play card. Or … everything in practice is a breakdown drill in the halfcourt where you stop to coach every single rep. Well, you’re never going to learn to play fast because everything is stopped and stagnant. It has to be built-in and it requires giving guys freedom.”

To supplement practices, Knight works with players to improve their mobility and balance. The goal is to keep them feeling bouncy and strong throughout the season rather than worn-down and dead-legged.

“Ninety percent of our conditioning is the way we practice and the way these guys do their work on an individual level,” Knight said. “Maybe 10% is because we do exercises in the weight room that don’t fatigue their legs too much. We’re trying to be really conscientious about not borrowing from the game to pay the weight room.”

They also rarely practice for longer than two hours. “Guys are still gonna be dead after practice,” former Gonzaga walk-on Jack Beach says, but not from sprints or marathons; just from high-intensity basketball. It shocks some newcomers. “You had to just hold onto the train and hope you didn’t fall off,” Kispert says. “But as soon as we started getting wide open dunks and 3s in transition, we started to get the reason why.”

It translated to in-game speed and endurance, and, crucially, to efficiency.

“To be efficient, you have to take great care of the ball and you have to take great shots,” Michaelson said. “We want to play as fast as we possibly can without losing those two things.”

‘The dam’s gonna break’ — How Zags wear down opponents

They apply that principle to possessions that begin with loose balls, missed shots or even makes. They often find Andrew Nembhard, their elite open-court point guard, who drives them down the floor via pass or dribble. Wings fill lanes, but often spot up at the 3-point line. Bigs run to the rim, but are also comfortable handling the ball.

They often meet resistance, but their pace brings advantages beyond uncontested layups. They flow seamlessly into a fluid, ball-screen-heavy offense, and attack scrambling defenses in search of open 3s, or deep post positions and easy entries.

[embedded content]

On one occasion against Memphis, they found Timme no more than four seconds after a Tigers dunk at the other end. On another, Nembhard got Timme a layup five seconds after a Memphis layup, before some Tigers could even turn their heads.

Gonzaga’s so-called secondary break is just as frightening as the initial wave. Its effective field-goal percentage in the first 10 seconds of possessions is 62.8%, and was 65.8% last year, per hoop-math.com. Both are top-five marks in Division I, and better than Gonzaga’s own eFG after a possession’s 10th second, a sign that it hasn’t lost “those two things” that Michaelson mentioned. (Its turnover rate is also the fourth-best among teams remaining in this year’s tournament.)

Opponents, of course, have relentlessly attempted to slow Gonzaga down — both to limit its efficiency, and to reduce the amount of times they have to limit it. Michaelson recalled opponents running “weaves 50 feet out on the floor” to burn clock and condense games. The last to bring the Zags to a true snail’s pace — 60 possessions per team or fewer — was 2019 St. Mary’s, which just so happens to be the worst team to beat them since the tempo shift.

Over three subsequent years, many have tried and failed. Most haven’t come close. Some have hung around for 40 or 50 possessions apiece, but that’s around the time Kispert would look across the court at the man he was guarding, see hands on knees, and smile. It’s around the time former Gonzaga assistant Tommy Lloyd would tell players: “The dam’s gonna break. Keep going. This team is gonna reach a point where they just crack.”

“And it would always be somewhere between the 8- to 13-minute mark of the second half,” Jones says, “where teams just completely crumble.”

“You could see the little leaks in the dam, the water kind of spraying out,” Kispert says. “And all of a sudden, we go on a 15-0 run and the game’s in the books.”

Sure enough, just last Thursday, in the 2022 tournament’s first round, 16th-seeded Georgia State led Gonzaga after roughly 54 possessions, around the time a typical Virginia game would be nearing its conclusion. But in Portland, there were 13 minutes remaining. By the time there were six remaining, after a flurry of fast breaks, Gonzaga led by 20.

It is, in a nutshell, why Gonzaga holds the longest active Sweet 16 streak, and why the record — jointly held by Duke (1998-2006) and North Carolina (1985-1993), who each made nine in a row — is within sight.