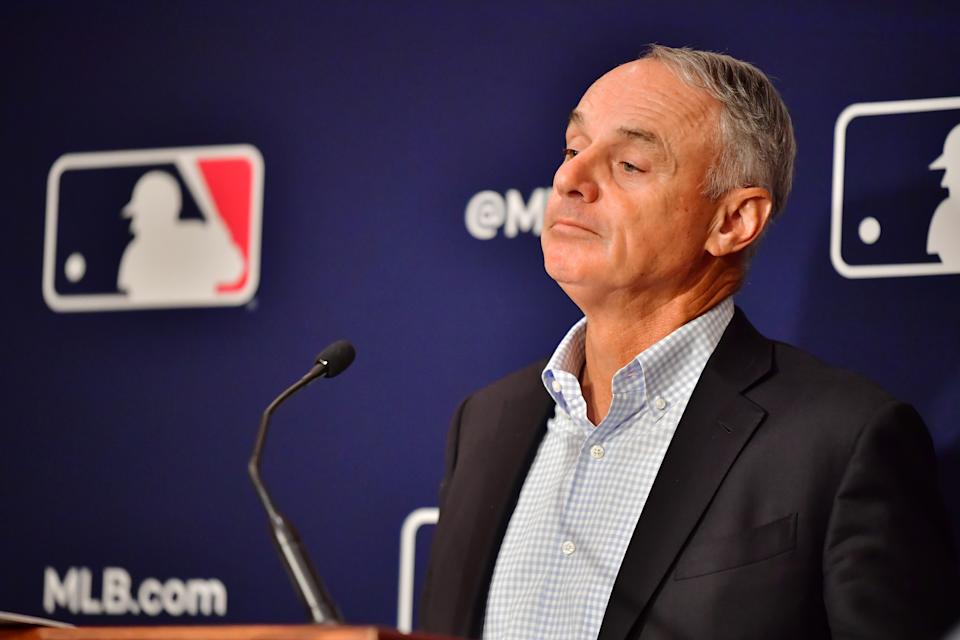

Major League Baseball was upset — the league doesn’t have feelings, but you know what I mean — on Tuesday that commissioner Rob Manfred’s response to me in a news conference with the Baseball Writers Association of America that morning had gone viral.

In the course of answering a question about minor league salaries, he said that he “kind of reject[s] the premise of the question that minor league players are not paid a living wage.”

And after some pushback, he reiterated: “I reject the premise that they’re not paid a living wage.”

This made instant news because it was callous — or, as critics of the commissioner might say, characteristically callous — and stood in stark contrast to the relatively recent surge of reports and first-person accounts about living conditions in the minor leagues. MLB’s concern was that the pull quote lacked context. Which is not wrong.

The shockingly low salaries in minor league baseball don’t include whatever signing bonuses a player received. (Although, Manfred specified that his response held true “even putting to one side the signing bonuses,” which was to his detriment as it’s the league’s strongest argument.) Further, the league also counts as compensation the free housing teams are now required to provide — to players, if not their families, although many teams have chosen to do so.

Manfred’s comment was a reflection of his belief that between other forms of compensation and the recent increase in minor league salaries — from $290 to $500 a week in Class-A and $502 to $700 in Triple-A — minor leaguers are paid a living wage.

OK, that was the context the league wanted out there. So now I want to give some context of my own.

Here’s what I asked: There’s obviously been efforts, both legal and potentially legislative, to address concerns around minor league pay. I just want to make sure that I understand, is the issue that the owners can’t afford to pay them a living wage or just don’t want to?

Manfred said he didn’t hear me so I restated it: The concern around the minor league pay from your owners, is the issue that your owners can’t afford to pay them more or they just aren’t interested in doing so?

And initially when Manfred rejected the premise that they are not paid a living wage, I pushed back: You reject the premise of the question that there are efforts being made to get them more money?

He explained that I had asked about why they’re not paid a living wage (so, he did hear me the first time?) and once again rejected it.

It made for a pretty good headline, and in the end was plenty revelatory. But, in my humble opinion, the question would have been just as good had I not said “living wage” the first time. Because being able to survive on a salary is hardly the only metric that matters.

Minor league salaries are artificially suppressed.

The antitrust exemption that MLB has enjoyed for the past 100 years gets mentioned a lot in critiques about the league’s apolitical claims and whenever owners cry poor. But it has no effect on major league salaries, which are carved out as an exemption to the exemption under the Curt Flood Act of 1998 and because the big leaguers are represented by a union whose CBA supersedes the antitrust law. As a result, major leaguers make millions of dollars because they’re able to justify that value to the more than $10 billion industry.

Without those protections, however, minor league minimum salaries are determined unilaterally by Major League Baseball, under the uniform player contract. They are not paid in accordance with their talent or effort or the time commitment required to perform a necessary function within the MLB ecosystem. They are not even paid in accordance with federal minimum wage laws after the league lobbied Congress for dispensation to pay their minor leaguers less than is required by the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938. They are not paid like people whose bosses appreciate baseball’s value to a local community and not just what it can fetch in TV deals. They are also often not paid enough to support themselves. All baseball players are paid only in season which means that even with the recent raises, even Triple-A players not on the 40-man roster make $14,000 annually. (The Federal poverty line for a single-person household in 2022 is $13,590.)

And, crucially, they are not paid as much as they think they deserve. Which is frankly all the reason they — or you, or I — need to ask for a raise.

Their request also happens to have garnered the interest, if not yet the explicit support, of the bipartisan Senate Judiciary Committee, which is exploring the impact the antitrust exemption has on minor league baseball in response to concerns raised by the nonprofit Advocates for Minor Leaguers. In a letter dated to Monday, the committee sent a series of targeted questions to Manfred, requesting a response by July 26.

“What effect would removing the antitrust exemption have on minor league player working conditions and wages? If a more tailored approach, like extending the Curt Flood Act to cover minor league players and operations, was taken, what would be the impact?” the letter asks, among other things. “Please describe any provision of the CFA that should or should not cover minor league players and why.”

Even without whatever responses are forthcoming, a spokesperson for Sen. Richard Durbin, the chair of the committee, said after Manfred’s comments on Tuesday, “It is reasonable to question the premise that MLB is treating the Minor Leaguers fairly.”

Given that MLB pays its employees so much less than they believe they deserve that the plight has attracted the attention of the Congress, and given that the league is repeatedly willing to take the PR hit that inevitably follows defending those salaries, it seems not just fair but necessary to ask why they aren’t higher. In the absence of normal market forces or other outside influence, there really are only two options: They simply can’t or they won’t.

So which one is it?