If you like free-agent fireworks, the 2022 MLB Winter Meetings provided them in spades. Beyond Aaron Judge’s historic deal to stay with the New York Yankees, the Philadelphia Phillies, San Diego Padres, New York Mets and Texas Rangers all went long to land the stars they wanted. Some teams reached surprisingly hefty agreements with pitchers who, crucially, pitch on a regular basis. And other contenders stayed conspicuously out of the fray.

So what does it mean? With 16 of the top 25 free agents by FanGraphs’ crowdsourced projections signed, we’ve seen the majority of the action at the top end of the market. In the first full offseason under the new collective bargaining agreement, we can start to unpack some of the ways front offices are operating and viewing players.

Here’s what the contract numbers so far tell us and what that could mean for the biggest names left on the board.

Those huge superstar deals are small in one crucial way

The dizzying top-line numbers for Trea Turner, Xander Bogaerts, Brandon Nimmo and Jacob deGrom sent a jolt through the baseball world. A few days removed from the peak of the signing spree, though, there are patterns in and reasons behind those deals that point to something other than pure largesse. And they drive home the importance of two acronyms you’re going to need to know to understand MLB transactions, if you aren’t already familiar.

CBT: Competitive Balance Tax. This is a soft salary cap that charges team owners a surcharge for exceeding certain payroll thresholds each season. As negotiated in the collective-bargaining agreement that ended the pre-2022 lockout, the lowest 2023 bar is $233 million, and that number will rise incrementally through the life of the agreement, hitting $244 million in 2026. The surcharges rise for teams that exceed even higher thresholds (hello, Mets) and/or stay above the thresholds for multiple seasons in a row. Most team owners, unsurprisingly, make an effort to stay under the initial threshold or dip below it regularly to reset their tax charges.

AAV: Average Annual Value. A team’s CBT number is calculated, crucially, using the average annual value of each player’s contract, not necessarily what a player is actually paid that season.

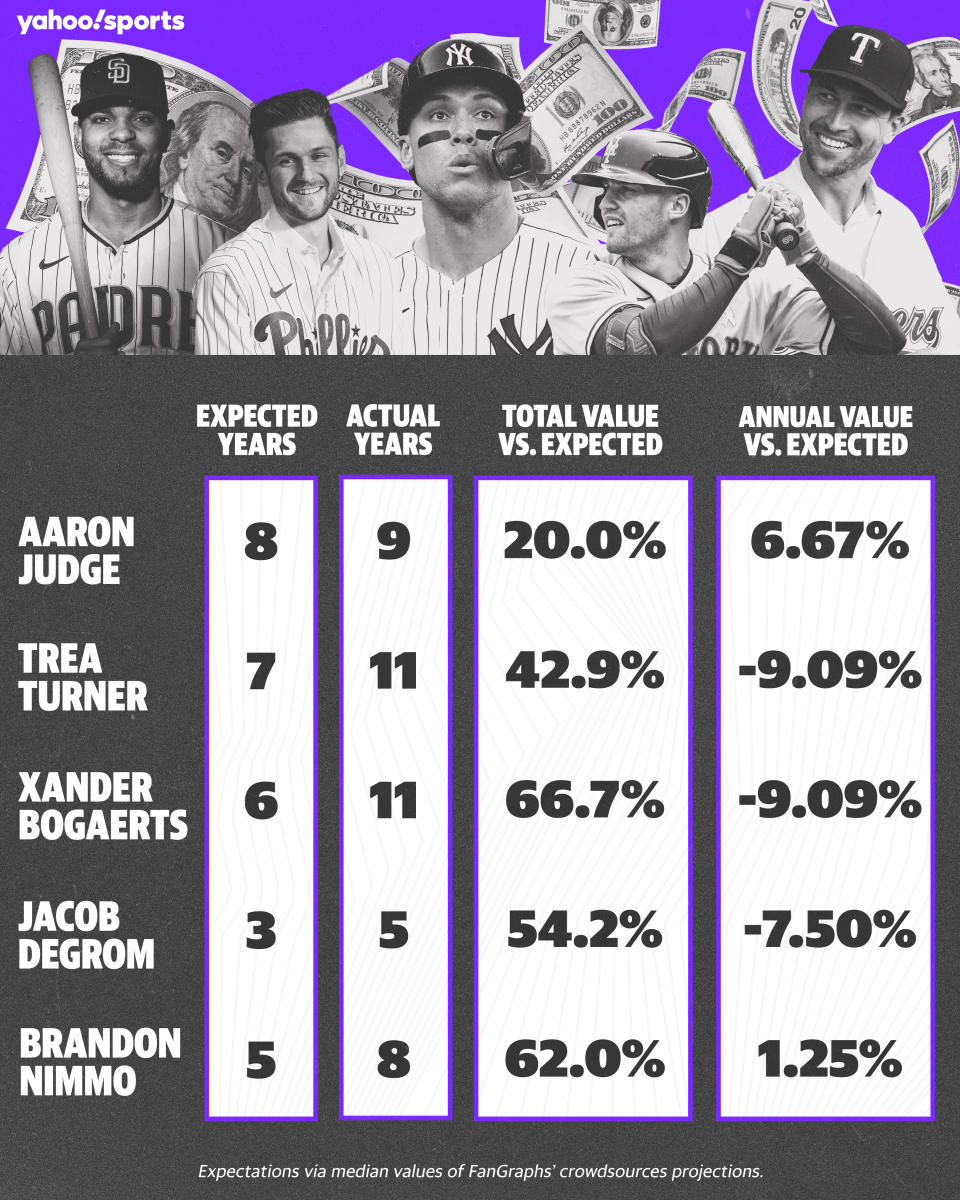

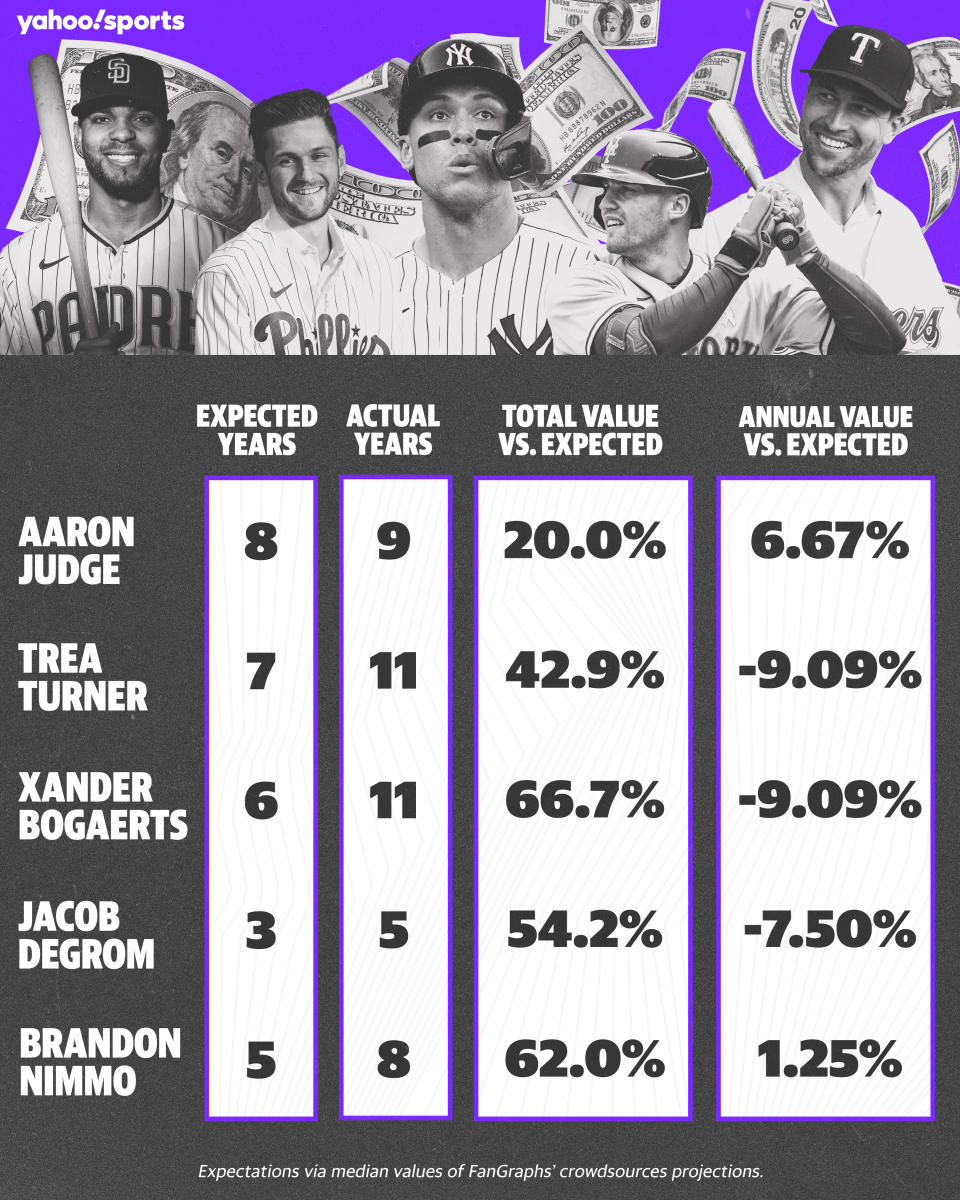

The initial takeaway from the rush of deals, dollar figures bursting at us like popcorn, was something to the effect of, “Whoa, that’s a lot of cash.” But using the median values from FanGraphs’ crowdsourced contract projections, you’ll see a stark difference in astronomical total values and the AAVs that go toward CBT numbers.

Here’s how the top five total earners of the winter so far compare to expectations from the beginning of the offseason.

Judge — he of the 62 homers and epic bidding war — did well on both, but not exorbitantly so on the annual value. Same with Nimmo. The Mets clearly wanted him back, and they used extra years to win him over, not more dollars per year. Then there are the contracts that landed Turner for the Phillies, Bogaerts for the Padres and deGrom for the Rangers.

The two shortstops who signed 11-year pacts, in particular, found matches with front offices keen on folding new stars into their existing constellations. The Phillies and Padres are already sailing past the CBT line for 2023, but paying Turner ($27.3 million AAV) and Bogaerts ($25.5 million AAV) less per year will give deal-happy executives Dave Dombrowski and A.J. Preller wider lanes in which to operate moving forward. Their new star shortstops aren’t dissimilar to Francisco Lindor or Corey Seager, but they will make $5 million-$9 million less per year, by CBT accounting.

The gap becomes even handier as the CBT rises. Add the fact that $25 million in 2032 is just worth less than $25 million in 2023, and the rationale crystallizes: The truth of Turner’s and Bogaerts’ market value is somewhere between the annual value and the total value. Will they be good in 10 years? Probably not, but they will likely outperform their salaries in the early years of their deals.

Remember when teams deferred money to lower the actual value of a deal but still help players set salary records? This is a little like that, but with an eye toward CBT surcharges. You can look at what the Phillies and Padres did as taking out loans on immediate, impactful help, with fixed, advantageous interest payments slated to come due in the early 2030s.

It’s a great time to be a reliable midrotation starter

If the superstar deals represent a give and take, there is one group of players whose contracts involve no such compromise. Midrotation starters who eat innings have teams over a barrel. Phillies signee Taijuan Walker and Chicago Cubs addition Jameson Taillon got four-year deals that beat their projected contract totals by more than 80% (!) and their projected AAVs by about 40% each.

Now, FanGraphs contract voters are informed observers, but this is where the industry makes its shifts known. Whether it’s the impending effects of the pitch clock or the continuing effects of MLB limitations on how many pitchers each team can carry, these No. 3-type starters are capitalizing on clubs’ anxiety about consistently filling out a rotation.

That holds true, to a lesser extent, for Chris Bassitt, reportedly the Toronto Blue Jays’ newest starter, and Zach Eflin, whom the Tampa Bay Rays signed to a three-year deal. Those pitchers beat their total and annual projections by about 30%. Bassitt is the best performer of anyone in this group, but he’s also the oldest, entering his age-34 season.

Even starters with more doubts baked in — such as Andrew Heaney (health, recent arsenal changes) and Sean Manaea (an ineffective 2022) — handily beat the deals the crowd saw them signing when the season ended.

How will this play out for Carlos Correa, Carlos Rodon and Dansby Swanson?

The biggest names remaining on the market — spoiler alert — are going to make more than we might’ve thought coming into the offseason. Carlos Correa, the youngest of this year’s top free agents and perhaps the hitter with the highest ceiling outside of Judge, must be fielding deals north of $300 million now. His median FanGraphs projection involved eight years and $256 million.

Swanson — a cut below Correa, Turner and Bogaerts but still very much a winning shortstop — could reasonably ask for a Nimmo-style deal that spans seven or eight years and eclipses $150 million, besting a FanGraphs projection of $141 million.

Rodon, clearly the biggest pitcher left on the market, is an interesting litmus test. He struggled mightily to stay healthy before his 2021 breakout but possesses a level of Cy Young potential that Walker, Taillon and Bassitt don’t. Do teams view him, at age 30, as a Verlander-type player to splurge on for a shorter term? Or as a player to stretch out to six years in hopes of getting an AAV bargain?

Other players likely to benefit from the market dynamics? Starting pitchers Nathan Eovaldi and Ross Stripling and perhaps even late-career comeback story Johnny Cueto.