Here we go again.

After six-and-a-half years of lofted fly balls that made people say, “Wait, that got out?” the 2022 season has instead featured a barrage of loud outs that make people — even pitchers — say, “Wait, that wasn’t a homer?”

And yes, a change in the baseball itself is again altering the state of play in MLB — this time kneecapping the home run surge that has kept scoring afloat in an age of ever-advancing pitching wizardry. Unlike the original “juiced” ball that entered the league around the All-Star break in 2015 — with fluctuations that peaked in 2017 and 2019 — this change came with some hint of warning that an adjustment was being made.

It was widely reported that MLB installed humidors at every park to standardize the storage of baseballs, and Insider reported that a less bouncy baseball supposedly introduced in 2021 was actually only partially integrated alongside more homer-prone 2020 balls — a phenomenon blamed on pandemic-related production issues. This season, the deader balls are being used everywhere, the Athletic reported.

But the implications of the shift (or shifts) have been more seismic than expected. Entering Wednesday’s games, MLB’s scoring was at 4.04 runs per game, which would be the lowest since 1981 if it held all season. It will likely rise some with warmer weather, but that still only gets you back to 2013 or 2014 levels. More alarming, the league batting average has plummeted to .232, the lowest on record and five points shy of 1968’s Year of the Pitcher. Trustworthy studies have already identified the ball as the obvious culprit, and MLB’s own stats show higher drag on the ball than in previous seasons.

Now, it’s true that the change in the ball only accentuates and reshapes existing trends — some of which MLB is working to reverse. The livelier ball led to more hitters swinging for the fences, which played into the sport’s gravitation toward its least dynamic plays — strikeouts, walks and homers. Batting average is down at least in part because defenses have become more advanced and more talented at covering the field. If changing the ball is a step toward a more visually exciting style of play, awesome. It’s not necessarily a bad direction, if other measures follow to curb the strikeout surge, but it could involve some extreme growing pains.

Logically, the thought process goes that hitters will grasp the new reality and adjust their swings and approaches to fit. It just might not be that simple.

In the short term, a member of one contender’s front office says the hitters most likely to thrive in spite of the deader ball are the ones whose production doesn’t rely as heavily on balls hit in the air. Strong plate discipline is the name of the game in the current environment — controlling the count and maximizing plate appearances is crucial when the ball isn’t flying out of the park. Step 1: Don’t strike out. Step 2: Get on base any way possible. Step 3: Profit.

In the long term? Well, significant adjustments are far more difficult for hitters than pitchers due to the reactive nature of their craft. While a wave of major leaguers recalibrated their swings to emphasize fly balls in the years of the juiced ball, it was a slow process. Amid skepticism that MLB will keep this deader ball in play for any amount of time, hitters are more likely to try and swing through it than go back to the drawing board.

That means the ball could scramble expectations and leaderboards for the 2022 season. A whole bunch of skills and tendencies are suddenly more or less valuable than what we thought a month ago, and a lot of statistical measuring sticks no longer mean exactly what they used to.

How does MLB’s dead ball kill offense?

Hitters entered 2022 thinking that hitting hard fly balls was pretty much the best thing you could do. The truth has been dramatically different.

The effects of the new ball have been so pronounced thus far that Statcast “expected stats” have been rendered essentially useless. Usually, the metrics use data on past batted balls to zero in on the process of hitting — how fast did the ball leave the bat and how high did you hit it? — instead of the results. So a player who smashed a fly ball at 105 mph with a 30-degree launch angle that just happened to go right to an outfielder could know, hey, keep doing that, it’s a hit 89% of the time. In any single game, a player might crush three balls with great expected numbers and come away with no hits. But over the course of the season, and across the scope of the league, the expected stats and the real stats come to mostly even out. Last season, for instance, the actual slugging percentage on fly balls across the league was .016 higher than the expected slugging percentage.

So far in 2022, fly balls have tallied an actual slugging percentage .224 lower than the expected slugging percentage based on how hard they’ve been hit. That gap, for context, is the same as the chasm between 2021 MLB slugging champ Bryce Harper (.615) and light-hitting shortstop Jose Iglesias (.397), who finished 113th in the category out of 132 qualified hitters.

There’s a lot of space in that “fly ball” category, though. Hitting the ball in the air is still undeniably better than putting it on the ground. To figure out which hitters are in better or worse shape this year, we need to understand which types of fly balls are suddenly landing in gloves and how they compare to other types of contact.

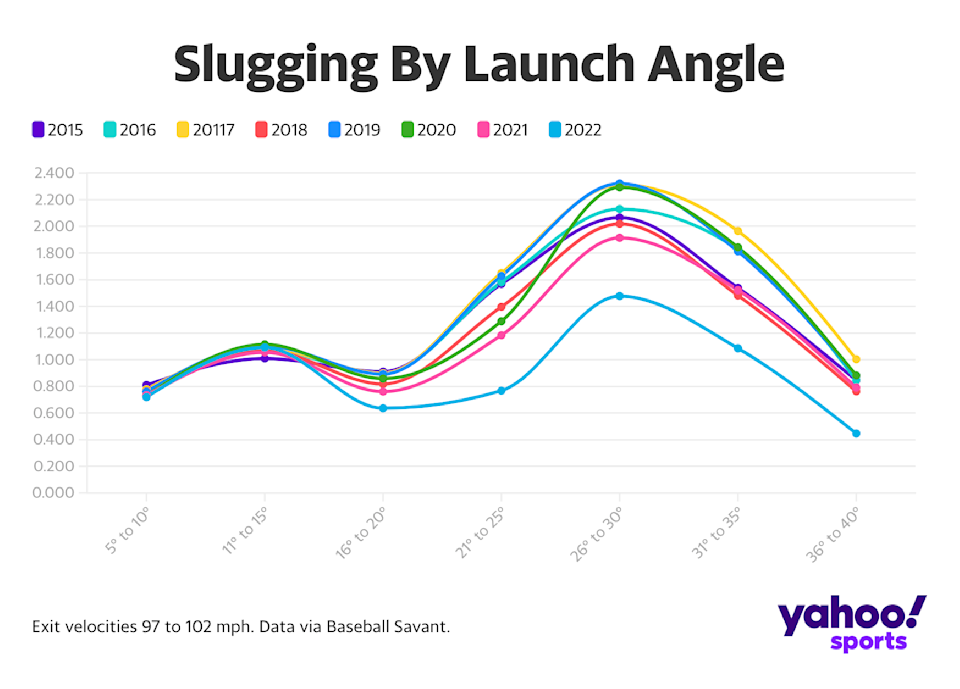

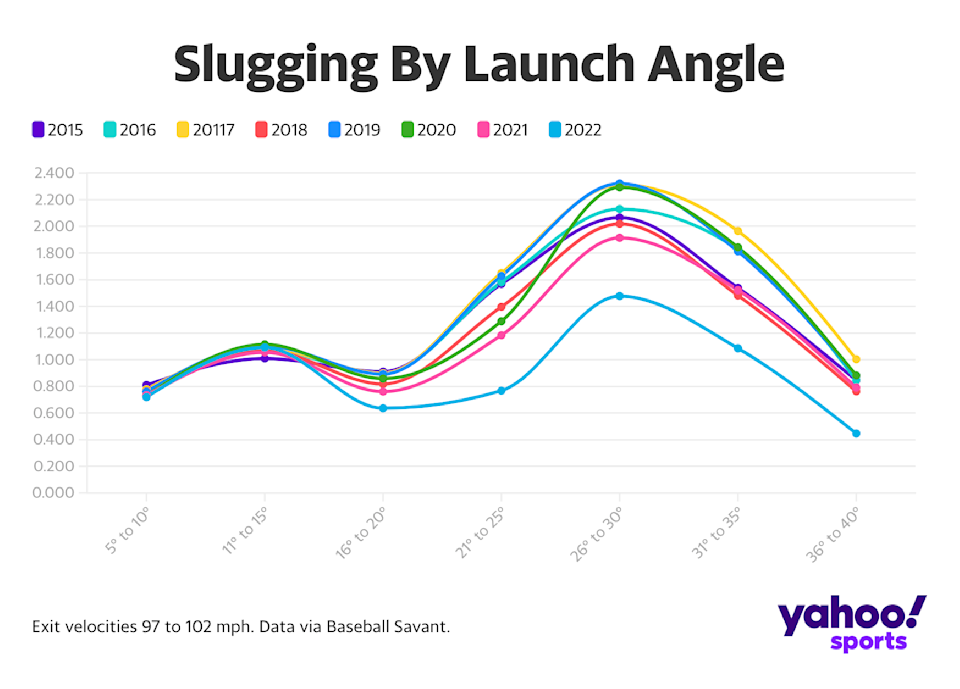

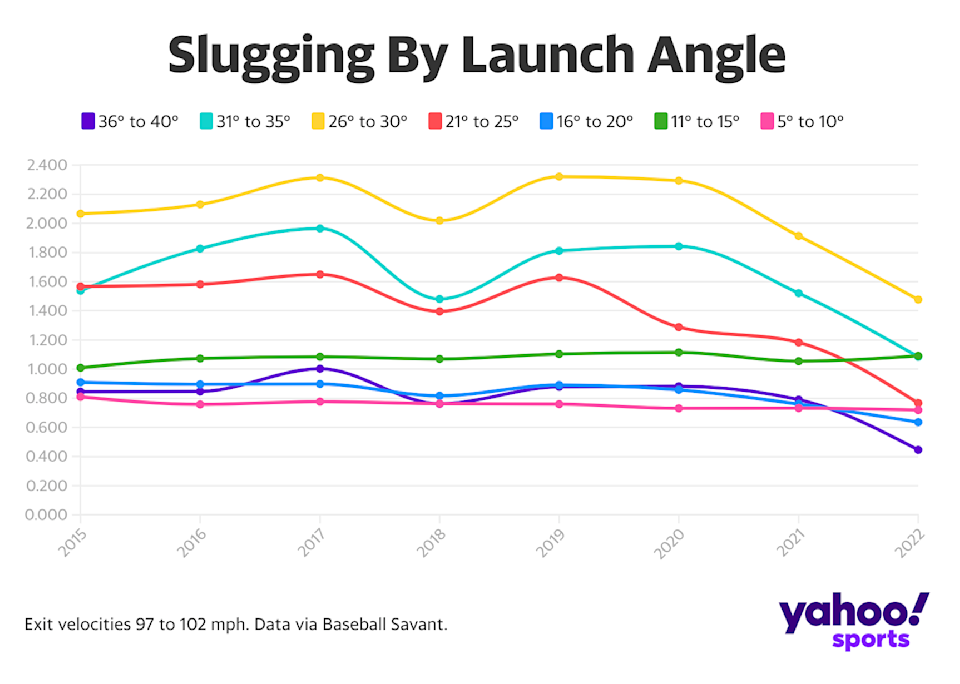

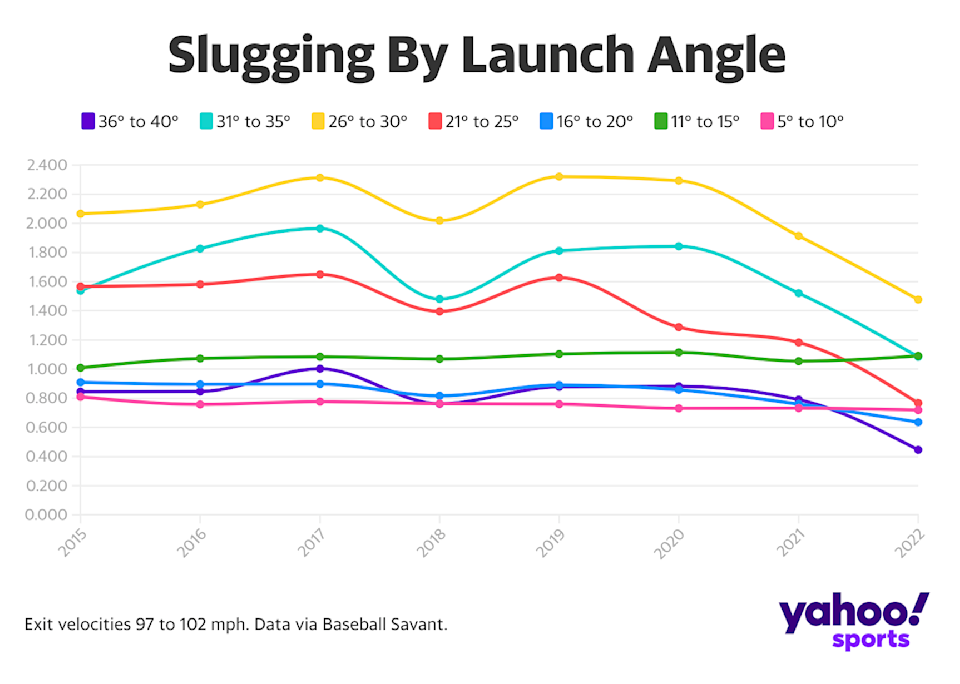

To begin understanding that, I took a slice of batted balls with exit velocities between 97 and 102 mph and broke them into brackets by launch angle. These are all hard-hit balls but well within every major-league hitter’s capability — a middle ground where a range of outcomes are possible. The lowest bracket, 5 to 10 degrees, would be low line drives that could skip off the ground in the infield in some cases. That highest bracket topping out at 40 degrees would represent huge sky-high fly balls. Homers are exceedingly rare below the 20-degree mark, but batting averages are generally higher.

As you scale up the launch angles, you start to blend risk and reward. Higher angles amount to more air time, which means small changes in the ball can have greater effects. Slugging takes a hit when the ball’s distance starts to fall back from “first row of seats” to “warning track” or from “one-hopping the wall” to “one hop in front of the outfielder.”

Here’s how those brackets have performed in slugging percentage since 2015.

As you can see, in this slice of batted balls, 2022 represents a massive departure from the hitting environment hitters have grown accustomed to. Line drives have remained steady, while the production of fly balls has cratered.

With the data flipped around just a little bit, you can more clearly see the biggest implication for hitters: Low liners with no out-of-the-park potential are close to eclipsing the slugging potential of homer-bait fly balls between 20 and 35 degrees. The value of super high flies in this range has all but totally tanked.

For those continuing to put the ball in the air, the new ball will challenge them to either a) hit it harder than before to achieve the same results or b) hit it in more advantageous directions, pulling toward the foul poles to find shorter porches or perhaps going the other way to stretch defenses.

Should Dodgers sluggers be worried?

The home run surge sparked by the juiced ball was, essentially, the democratization of power hitting. No one started blasting 65 dingers, but a lot of previously unassuming hitters started slugging 25, 30 or more. The deader ball could essentially reverse that, returning big homer numbers to the realm of only the very strong or very strategic.

Yet a great many careers are built on the value of lifting the ball as much as possible, even without crazy power. Take big-ticket Texas Rangers signing Marcus Semien. In exploring his abysmal start — he’s batting .163/.233/.217 with no homers a year after belting 45 — Baseball Prospectus analyst Robert Orr outlined the recipe for disaster in microcosm.

“When most players come up short of hitting a home run on a hard-hit line drive they can often still get extra base hits from the ball making it to the wall,” Orr wrote. “This isn’t the case with Semien, since his variety of contact — high, slower traveling arcs — is more likely to end up in the glove of an outfielder if it comes up short.”

The other problem? He’s hitting more of his fly balls to the middle part of the field (read: the biggest part of the field).

So we have two big factors: Reliance upon higher fly balls for production and the tendency to hit them toward the middle of the field.

I took the last three seasons and looked for the players who have most frequently hit fly balls between 21 and 40 degrees to the middle of the field. Those balls made up more than 15% of batted balls for sluggers like Cincinnati Reds star Joey Votto (20.3%) and a duo from the middle of the Los Angeles Dodgers order — Justin Turner (18.4%) and Max Muncy (18.3%).

Of Muncy’s 83 homers from 2019 to 2021, 42 came on these sorts of balls that are now dramatically more difficult to hit out. So far in 2022, he has limped out to a .190/.310/.261 start. And yet, buoyed by an excellent walk rate and strong average exit velocities, he’s probably in better shape to overcome the change than Turner. The stalwart 37-year-old third baseman was one of the most prominent hitters who revitalized his career by leaning into the so-called fly ball revolution, yet at this stage of his career, his declining exit velocities may not be enough to maintain the power that has made him such a threat.

That power wiggle room could also be significant. The hitters who have made the most hay from now-borderline fly balls — 21 to 40 degrees, between 95 and 100 mph — over the past three years include Semien, Mookie Betts, Alex Bregman, Whit Merrifield and Jorge Polanco.

Whose skills could play up in 2022?

Who benefits from the dead ball? Well, mostly pitchers and their agents. But some hitters are more equipped than others to have league-leading seasons.

This is a little bit more complicated than spotting hitters who might be taken down a notch. There are a lot of sluggers who could see some ill effects, but also power through them. The easiest illustration is Aaron Judge. The Yankees superstar strikes out quite a bit and makes his living in the air. The difference is he hits the ball so hard it rarely matters where the wall or the defenders are standing.

So, no one is “doomed” by the dead ball. Some hitters who might look disadvantaged because of one trait — new Phillies star Nick Castellanos hits a lot of fly balls to the middle — turn out to be relatively safe because they also mix in a lot of line drives or pull the ball plenty.

Certain hitters are particularly recession proof in this context, though.

The basic guidelines are the same as any year: The fastest way to become a star hitter is to control the strike zone and build a base of competence by walking and avoiding strikeouts. Next up: Hit the ball hard and give yourself more margin for error. So Mike Trout, Juan Soto, Vladimir Guerrero Jr., Bryce Harper and company aren’t likely to go anywhere.

With the data so clearly illustrating how lower liners are comparatively more valuable than they have been in recent seasons, hitters who are already adept at ripping those reliable hits through gaps might rise on more leaderboards. Based on the patterns of the past three seasons, that would count as a win for Rafael Devers, Freddie Freeman and Manny Machado. It would also lend some context to the early season success of up-and-down line-drive hitters like Eric Hosmer and Alec Bohm.

One helpful trick that might beat all the rest? If you’re going to hit the ball in the range of fly balls that has been so gutted by the dead ball, pulling it can help you find optimal results anyway. The hitters who pulled those 21- to 40-degree flies the most often? Jose Ramirez and Nolan Arenado.

So far in 2022, the best hitters in baseball, by the park-adjusted offensive metric wRC+, are Trout, Ramirez and Arenado.