By the spring of 2018, the plans were ready, permission had been granted, and the outstanding legal objections had been settled but just as work was to begin on what would be the most expensive stadium built in the history of British sport, Roman Abramovich pulled the plug.

It was a brief club statement on the club’s website on May 31, 2018, which made no reference to Abramovich’s recent decision to withdraw his Home Office tier-one visa renewal application. The club cited then “the current unfavourable investment climate” and has since never commented further.

Around ten months ago, the planning permission was allowed to expire.

The local London authority, the borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, had granted all successful planning applicants one year’s extension in light of the Covid lockdown, but even that was not enough for Abramovich to change his mind.

Stamford Bridge, Chelsea’s 41,800-capacity home of 117 years – the only home the club has had in its history – is the intractable problem that none has solved. Chelsea are the European champions, the world champions, in a stadium that was last rebuilt significantly in the 1990s. To earn the FFP-clean revenue to compete without a billionaire benefactor they first need the modern stadium, with lucrative hospitality facilities. And to build that in west London will require the kind of money that no-one has ever spent on a stadium before.

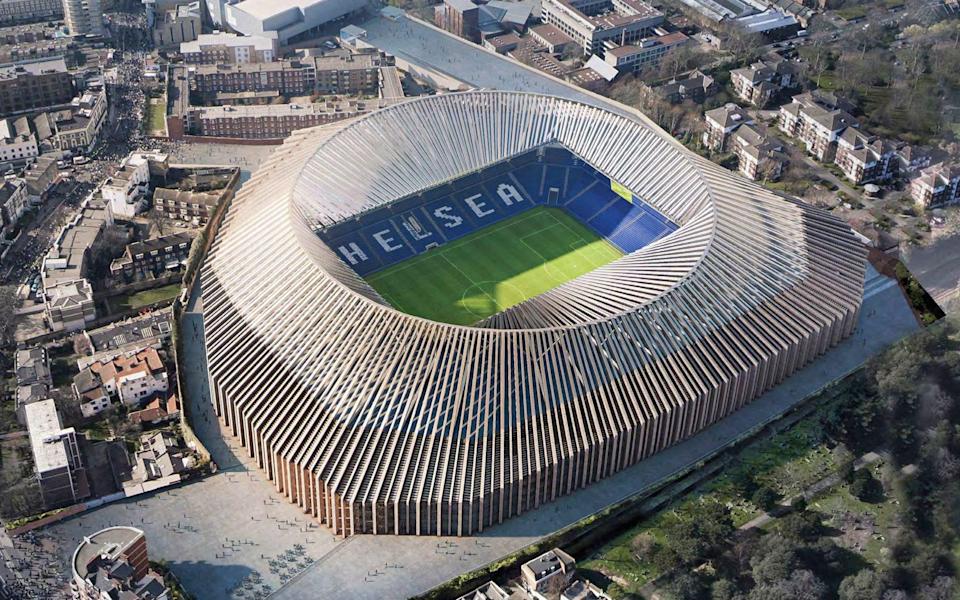

If the Abramovich years are to be over soon, Chelsea’s new owner will find that there are no alternative sites left in west London – if such a move was even possible. In 2017, to build the 60,000-capacity stadium design that the club announced – as well as a three-year tenancy at Wembley, while the work was undertaken – was conservatively estimated at £1.4 billion. The cost is now estimated at closer to £2.2 billion. Even when the plans were on course there was no indication as to where the money would come from, other than the assumption it would be Abramovich’s private fortune.

For the club’s Russian owner, having the best stadium in London was important. From a financial sustainability point of view it was crucial.

The capacity of Stamford Bridge falls every time broadcasters’ requirements encroach further. The club’s annual matchday revenue – earned from ticket sales – hit a high of £96 million in 2011-2012 and settles around £70 million-£80 million excluding Covid lockdown seasons. Nothing like what Manchester United earn from the 75,000-capacity Old Trafford – with a peak of £147 million in 2017. Even Arsenal regularly earn more than £120 million from the Emirates. Tottenham Hotspur and West Ham’s stadiums also have much greater potential.

Did Abramovich realise in 2003 that the freehold for the stadium was not included in his £150 million purchase? Any new owner could hardly fail to know that Chelsea are tenants of an independent entity, the non-profit plc Chelsea Pitch Owners, which was loaned the money to buy the freehold, around £10 million, by the previous owner Ken Bates. One of the greatest golden shares ever bequeathed to a club’s fans gave them a 199-year ownership of the pitch their team played upon.

Under the terms of CPO’s freehold Chelsea pay a peppercorn rent but any owner that moves the club away from Stamford Bridge without CPO permission forfeits the right to call themselves Chelsea Football Club. In 2012, the club’s board at the behest of the owner, tried to buy the freehold from CPO but, in a shareholder vote, failed to reach the threshold that would trigger a forced sale. A healthy scepticism among fans who had seen the club almost forced out of existence by property developers in the 1980s galvanised CPO shareholders. They appreciated Abramovich’s investment but their concern was what might lie beyond him. Ten years on and the wisdom of that stance is evident.

Life would have been easier for Abramovich’s board without CPO and while the relationship is cordial it has been strained over the years. Even a recent decision by the club to improve the stadium wifi with a new mast on the roof had to be approved by CPO’s board. The outstanding loan to CPO now stands at around £8 million and will take decades to pay off. Nevertheless, the most valuable piece of football real estate in the English game is safe. When Tracey Crouch’s team gathered evidence for the fan-led review of football there was particular interest in the CPO model.

For some time it was thought that Abramovich favoured a move east to Battersea Power Station or a site further north in White City where he would build a new stadium. Fans were told that there was simply not the capacity on the Stamford Bridge site, opened in 1905 by Chelsea’s founder Gus Mears, and with just one exit route onto Fulham Broadway. When it was acknowledged finally that there was the potential to do so, the 2017 plans looked spectacular. A stadium bowl was to be dug downwards to create the space. The District Line and Southern Line to the east would be built over.

The two hotels and health club on site would be demolished.

Instead of the steel and glass of modern stadium design there would be bespoke brick piers supporting an asymmetrical “faceted polygon” shape to fit the site. A right-to-light case was settled by a family living nearby.

To the west of the stadium, part of the Oswald Stoll development housing for veterans was acquired. Planning documents included measures to minimise any impact on the Victorian catacombs in West Brompton cemetery across the railway tracks. It was to be the most expensive West London basement excavation of all time; the ultimate status symbol for Londongrad’s richest man. Whether it will ever be built is another matter.