The Mets introduced Kodai Senga on Monday. On Tuesday, it was Justin Verlander who got the pomp and circumstance at Citi Field, as GM Billy Eppler talked about finishing the offseason by adding around the margins soon after saying most of the Mets’ heavy lifting was done.

Maybe New York would reunite with Michael Conforto, or sign someone like Trey Mancini. Perhaps their last big move of the offseason would be trading for Chicago White Sox closer Liam Hendriks, whom they were linked to on Tuesday shortly after the Verlander news conference ended.

Nope.

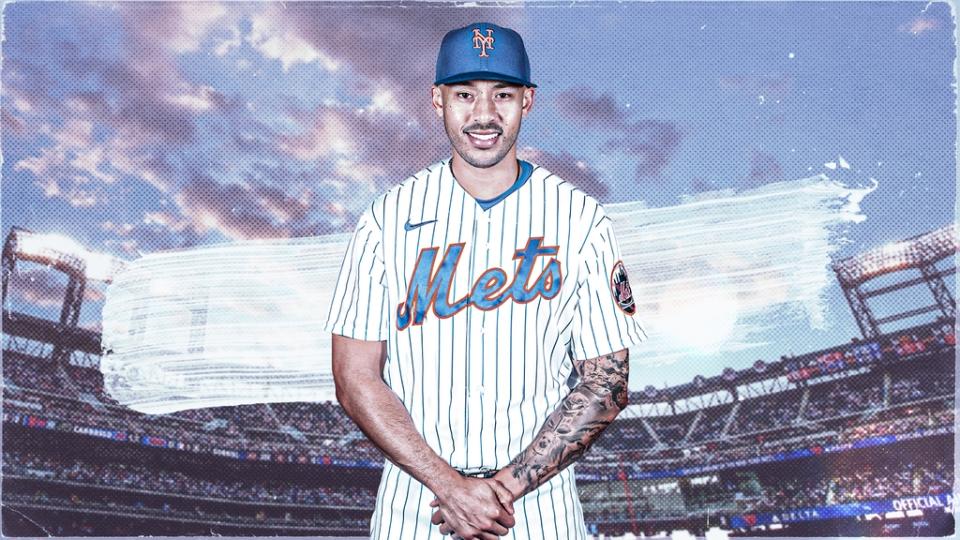

The Mets’ last enormous move (we think) of what has been a truly historic offseason in terms of spending was owner Steve Cohen leading the charge as they came to an agreement with star infielder Carlos Correa on a 12-year deal worth $315 million in the middle of the night as Tuesday became Wednesday and most of the baseball world was asleep.

And it wasn’t the time of night (it broke around 3 a.m.) that was the most disorienting thing about it.

No, it was that Correa had recently agreed to a 13-year, $350 million deal with the San Francisco Giants after the Mets made a late bid. That deal hit a snag on Tuesday due to something that came up in Correa’s physical, but the breakneck speed at which Correa went from a Giant to a Met was one of the wildest turns of events in the history of free agency. That is not hyperbole.

So, what now?

The Mets, with an astonishing payroll of roughly $384 million, are now full of superstars — and they’ve added all those stars without having to give up any of their young talent.

And as SNY contributor Joe DeMayo pointed out, none of the players the Mets have signed this offseason were attached to the Qualifying Offer. That means the Mets didn’t even lose any draft picks during this spree.

With Correa now on board pending a physical, and set to play third base next to Francisco Lindor at shortstop, here’s what the ripple effects could be…

Is that it for the huge moves?

As we’ve found out over the last few months, it will never be wise to say the Mets and Cohen are definitely out on anyone, or that they’re done making splashes of any kind.

But it kind of feels like the Mets are now set with their offense, and that signing Conforto or Mancini would be superfluous with the amount of firepower that is now in the lineup with the addition of Correa.

As far as elsewhere on the roster, SNY’s Andy Martino suggested Wednesday morning that a pursuit of Hendriks was still possible. And with the Mets possibly shedding some salary in the coming weeks (not that they have to), fitting in Hendriks’ $14 million salary for 2023 wouldn’t be a stretch.

Regarding what the agreement with Correa could mean for potential big moves at the trade deadline and/or next season, the Mets have plenty of money coming off the books after this season and in the coming seasons, which we’ll delve into in a bit.

With Correa at third base (pending passing his physical, of course), Escobar is now a man without a position.

If the Mets keep Escobar, he could be the perfect short end of a DH platoon with Daniel Vogelbach, since the switch-hitting Escobar is much better against left-handers than right-handers.

If the Mets decide to trade Escobar, who is set to earn $10 million this season and has a club option for 2024 worth $9 million (with a $500,000 buyout), it shouldn’t be difficult to find a taker. And the Mets would be able to shed some money in the process. Again, not that they have to.

Escobar struggled for a while in 2022 in his first season with the Mets, but he caught fire late in the season, slashing .321/.385/.596 with eight homers over the last 30 games of the season spanning Sept. 1 to Oct. 4.

In addition to Escobar, the Mets could also possibly deal Carlos Carrasco and/or James McCann, with Martino reporting recently that they were both being dangled on the trade market.

What about Brett Baty and the prospects?

Before the Mets agreed to terms with Correa, Baty — who impressed in his first taste of the majors in 2022, showing off a polished approach at the plate and flashing high exit velocities — was the heir-apparent at third base.

Now, with Correa expected to be at third base for the next 12 years, Baty’s exposure to left field will get “accelerated,” Martino reported on Wednesday.

Baty has played primarily third base in the minors, but he started 11 games there in 2022 after starting 18 games there in 2021. So perhaps Baty is the Mets’ Opening Day left fielder in 2024 if Mark Canha leaves in free agency, or maybe Baty starts splitting time with Canha there this season.

When it comes to Ronny Mauricio, who was just named the Dominican Winter League MVP, he is now blocked on the infield. And he might also be blocked in the outfield, where he was expected to start transitioning to during spring training.

As far as Francisco Alvarez, this changes nothing. He is still the Mets’ catcher of the future, whether he takes the reins by Opening Day in 2023 or some time after.

Is the payroll too high now to go after Shohei Ohtani?

No.

There are two reasons why the Mets should still have a serious shot at landing Ohtani, either via trade this summer (with the thought being to extend him) or via free agency after the 2023 season.

The first is that the influx of cost-effective prospects soon, including Baty and Alvarez this season, will help knock the payroll down significantly.

The second is that the Mets should have at least $66 million coming off the payroll after the 2023 season — and that number could reach $109 million if Max Scherzer opts out and rise even higher if Adam Ottavino opts out.

The Mets, aside from the pending deal with Correa, only have three other long deals on the books — the ones to Lindor, Edwin Diaz, and Brandon Nimmo. And their biggest deals in terms of annual value ($43.3 million to Verlander and Max Scherzer) will be off the books after either 2024 or 2025.

Meanwhile, the Mets’ overall salary commitments drop sharply in 2025 and 2026, creating additional room for Ohtani should the Mets decide to pursue him.