Long before — long, long before — the advent of minute-to-minute media that spanned continents, which developed some measure of global information dialect, which rinsed sports through its wash cycle, which unspooled partly into GOAT debate hokum, a common tongue was Pelé’s brilliance.

In 1961, just one World Cup title and a handful of club trophies into his mighty career, Brazil president Jânio Quadros had Pelé formally declared a “national treasure,” which legally entangled him from being pried away from Santos in São Paulo just as Europe was becoming the epicenter of talent and resources in world football. In 1962, Pelé was injured in the second game of the World Cup and missed Brazil’s run to another title. In 1966, he was hacked down at the knees by opposing defenders so harshly Brazil failed to advance out of the group stage.

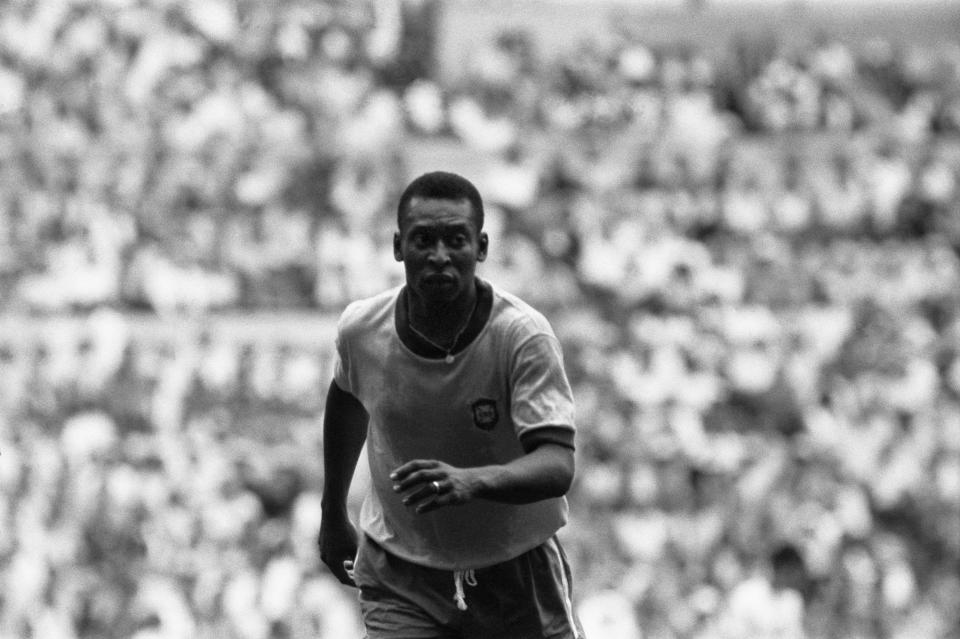

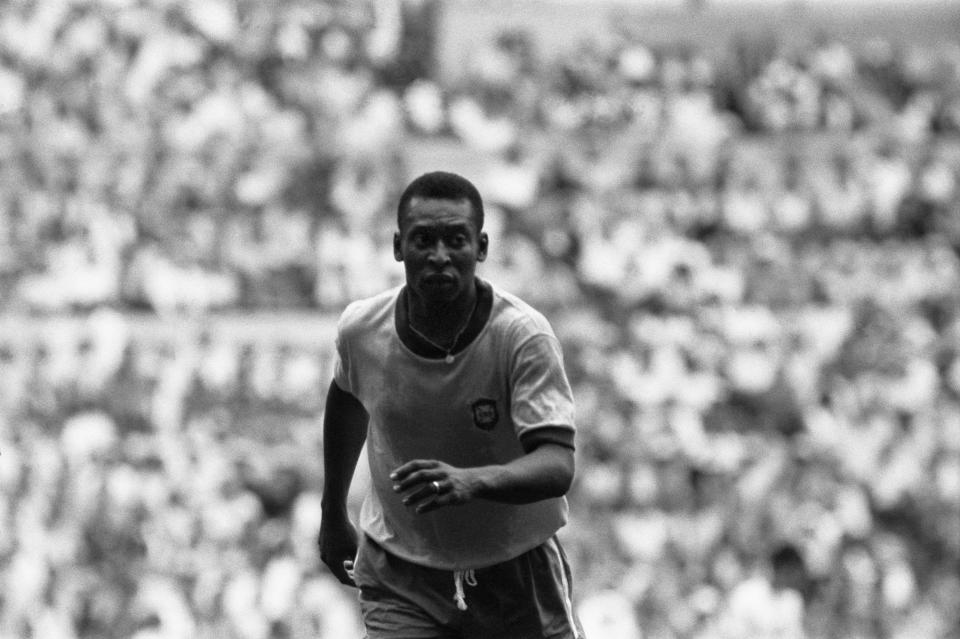

So by 1970, Pelé’s greatness, his mastery, his flourish, his improvisation, was widely acknowledged, but with elements of a tall tale. The perfect stage to showcase it beyond doubt? That summer’s World Cup, the first one broadcast live to a worldwide audience. And showcase it he did, especially in the final, a resounding 4-1 triumph over Italy where he opened the scoring with a picturesque header and helped close it with one of the greatest passes ever amid a legendary sequence.

“I told myself before the game, ‘He’s made of skin and bones just like everyone else,'” said Italian defender Tarcisio Burgnich, who was tasked with marking Pelé. “But I was wrong.”

Pelé died Thursday at the age of 82, and the tributes came pouring in. Ever since that 1970 tournament, Pelé’s peerless iconography only ever expanded, thanks in no small part to those who promulgated it well before now.

Cristiano Ronaldo. Johan Cruyff. Franz Beckenbauer. Alfredo Di Stéfano. Ferenc Puskás. Sir Bobby Charlton. Bobby Moore.

Each on the shortlist for best and most influential players in history.

Each united in their overt praise for Pelé.

“I refuse to classify Pelé as a player. He was above that,” said Puskás, the Hungarian striker recognized as the sport’s first international superstar and whose name still graces FIFA’s official goal of the year award.

“Pelé is the greatest player in football history, and there will only be one Pelé in the world,” said Ronaldo, whose monumental individual and club success in the current era has wedged his status into rarefied air.

“He is the most complete player I ever saw,” said Beckenbauer, the positional revolutionary who might be the greatest defender ever and brought heaps of trophies to both Germany and Bayern Munich.

“Pelé was the only footballer who surpassed the boundaries of logic,” said Cruyff, whose “Total Football” proponance reinvented the game at the international level with the Netherlands and later at the club level with Barcelona.

Cruyff’s primary ideological successor was Pep Guardiola, whom he coached at Barça. And when Guardiola coached Barça himself, the centerpiece of his success was Lionel Messi, whose World Cup title earlier this month vaulted him either past or shoulder-to-shoulder with Pelé, depending on who you ask.

We won’t rehash that here. We won’t litigate eras, or delve into which player rises highest past the bar. We’ll simply point out that before Pelé, there was no bar.

No player has drawn the level of praise Pelé has. Perhaps that’s because that global information dialect has grown too big for its own good, with bad faith articulated simply for the sake of attention, and too many slobs overeager to have their preference validated, permanently diluting the well stream and gatekeeping any player from ever being universally acclaimed again.

That’s a more muddied conversation. This one’s clear: Pelé was the greatest players’ greatest player.

“I sometimes feel as though football was invented for this magical player,” said Charlton, as accomplished an Englishman as any ever.

“The best player ever? Pelé. Lionel Messi and Cristiano Ronaldo are both great players with specific qualities, but Pelé was better,” said Di Stéfano, the Argentine-born Spanish international whose goal-scoring proficiency was foundational to both Real Madrid and the competition we today know as the Champions League.

“I remember [former Brazil manager João Saldanha] being asked by a Brazilian journalist who was the best goalkeeper in his squad. He said Pelé. The man could play in any position,” said Moore, whom Pelé himself called the best defender he ever faced.

Pelé shared the FIFA Player of the Century award with the brash supernova that was Diego Maradona after the latter ran away with online fan voting, which skewed toward the younger, more internet-savvy generation. FIFA stepped in and polled a group of journalists, officials and coaches. Pelé won over 70% of that vote.

Even Maradona managed to muster his own version of high praise. “It’s too bad we never got along,” Maradona said, “but he was an awesome player.”

Before Pelé, players never even dared execute the audacious moves we see all over the pitch today. Before Pelé, the No. 10 shirt was just another squad number. Before Pelé, nobody was really sure a “greatest soccer player of all time” could exist.

After Pelé, everyone agreed who it was.

“When Pelé scored the fifth goal in [the 1958 World Cup final],” said Swedish defender Sigge Parling, “I have to be honest and say I felt like applauding.”

Pelé just had that effect on people. Especially the best to ever play his sport.