“Oh, you want to hear about attending A’s games? As anyone who’s been within earshot of me for more than three minutes can attest, I’m happy to talk about not attending A’s games.”

So opened an email from Danny Willis, a 39-year-old Oakland A’s fan — he says the Bash Brothers were “basically superheroes” — living in Concord, California.

Attendance matters — that’s why they have the seats and the beer stands and why the 2020 season was so dissonant to watch. Lack of attendance matters, too — a data point in debates about the waning popularity of baseball or something to wonder about when it comes to even successful Florida markets.

And since baseball, as anyone with a clear-eyed sense of the game is quick to tell you, is a business, buying tickets (or not) is a way for fans to insert themselves into the equation.

Which is why I wanted to hear from fans how they viewed their in-person participation in seasons that are all but lost from the outset. Weighing frustrations against futility against enthusiasm for the teams they love. The low attendance numbers can tell a simple story, and are often cited, about how on-field performance affects a fanbase. But I wanted to hear a little more about why — both from the people who don’t go and those that still do.

I solicited feedback from fans of the: A’s, Cincinnati Reds, Baltimore Orioles and Pittsburgh Pirates. They’re not strictly the worst-attended teams (although, the Pirates and A’s are), but they’re teams in various stages of losing whose behavior has publicly alienated fans.

Reds — ‘Ownership should not feel good putting this product on the field’

Probably I wouldn’t even be writing this story if not for Reds president Phil Castellini.

On the day of the team’s home opener, the son of the Reds’ controlling owner Bob Castellini was asked why fans should continue to have faith in the organization that hasn’t won a postseason game in a decade and chose to dump talent following a season in which they finished with a winning record.

“Well, where are you going to go? Let’s start there. I mean, sell the team to who?” he said on the radio. “That’s the other thing — you want to have this debate? If you want to look at what would you do with this team to have it be more profitable, make more money, compete more in the current economic system that this game exists? It would be to pick it up and move it somewhere else. And so be careful what you ask for.”

Rather than give fans a reason to believe, he opted to sneer at them for not having better options. And then immediately juxtaposed their own forced fidelity with a barely veiled threat to take the team out of Cincinnati.

“What did the fans do to deserve the kind of sentiment that seems to be coming from the ownership?” wrote Stephen Palluconi, 36, of Westchester, Ohio. (All interviews were conducted over email.)

Once such an avid fan that he says he would watch or listen to 150 Reds games a year, Palluconi has disengaged this season. He rode the rollercoaster of the past 10 years of loyalty before finally hitting a breaking point this offseason. Many Reds fans described a similar tolerance for what they believed to be strategic rebuilds previously.

“This year, however, there’s no such buy-in,” wrote Clay Marshall, a 43-year-old Reds fan living in Los Angeles who is reconsidering his annual trip back to Great American Ballpark.

The past two seasons gave Reds fans hope — in 2020, they made their first October appearance since 2013, and last year’s club would have qualified for the now-expanded postseason field. They seemed to be building toward something.

“When they dumped the majority of the team in the offseason it was just another reminder the front office is clueless,” Palluconi said.

With an explicit nod toward cutting payroll, the team dealt Jesse Winker, Eugenio Suárez, Tucker Barnhart, Sonny Gray, Amir Garrett, and declined a $10 million option on Wade Miley.

“As a fan, I feel deceived and betrayed,” said Marshall, “and as a result, I have no interest in spending several days of my life and hundreds of dollars to travel cross-country to see games that won’t matter a lick.”

“All I ask is for them to be competitive,” wrote Will Mullins, 23. “I’m not looking for much more than that.”

A month into the season, the Reds are not competitive. By far the worst team in baseball, they’ve gotten off to a historically demoralizing 8-24 start. Their attendance numbers are, comparatively, robust. At an average of 17,286, the crowd size in Cincinnati is only seventh lowest in MLB. But some of those fans are arriving with bags over their heads and a clear message imploring Castellini to sell the team. (Others have taken that sentiment to the sky.)

“Maybe it will put pressure on the majority owner from the other owners if the fanbase is livid,” Palluconi said. “Collectively I’ve never seen Reds fans this upset, and we are very united.”

Except, that is, on the issue of whether to go to games. Nearly everyone acknowledged that frustrated fans face a conundrum: You can withhold your ticket sales to make a point, but then you’re depriving yourself of the experience. And besides, do the people who matter even care?

“On one hand, the Castellini family doesn’t deserve the support,” said John Wilson of Louisville, Kentucky. He said not going wouldn’t necessarily be a statement, bad teams are just less compelling. And so he’ll scale back his attendance this summer, but ultimately, “I will still go to a few games this season to support the workers and players that show up to the stadium. They didn’t choose the budget. They want to win and wish they had the resources to do so.”

“I’m torn because I want to support the young players on the team like [Jonathan] India and [Hunter] Greene and [Tyler] Stephenson,” Palluconi said. “But I feel like empty seats will send a message like, hey, it’s not okay what you’ve done to the roster.”

“Ownership should not feel good putting this product on the field with the hopes of fans attending. However, while I like the Reds and root for them, I enjoy watching Major League Baseball,” said Matthew Vale, a schoolteacher who noted that at least the tickets are cheap.

Some fans, like 28-year-old Matt Elliott of Hamilton, Ohio, are threading that needle by attending local minor league games. After all, getting excited about the Triple-A team in Louisville might be fans’ best hope this season.

Unless, of course, they want to see Joey Votto. The career-Red, now 38 and in the final two years of his contract, is a source of particular ambivalence for fans who want to soak up every game the franchise icon has left to play.

“I think what is most frustrating about this whole situation is that we took the greatest player our franchise has seen in 50 years and wouldn’t invest the resources required to give him a fair chance,” Wilson said.

“Joey Votto is Reds baseball for me,” said Tyler Brickey. “Nothing ownership says or does will change that.”

He has no plans to go to fewer games this season. Because of Votto, because it’s the players — not the Castellinis or the front office — on the field, and because, “the financial structure of the sport virtually guarantees the owners get their money.”

Which is, of course, the rub. If you love baseball, you’re always enriching ownership. And so even clear-eyed fans aware that it’s a Faustian bargain will often make the deal.

Chad Conant is a father to a teenager who loves Mets ace Max Scherzer, despite living in Cincinnati. Although they originally had plans to go to opening day before the lockout delayed the start of the season, Conant won’t go to any games this season — that is, unless the Mets come to town and Scherzer is scheduled to start.

“My kid will get the experience he deserves,” he said. “It’s not his fault Phil Castellini is a jackass.”

Pirates — ‘I only go if I don’t have anything better to do’

For a couple of years in the early 2010s, the Pirates snuck into the postseason with a wild-card berth. None of those trips went particularly well. Outside that, they’re working on extending three full decades of disappointment this year with their 13-18 start. The Pirates — with their low payroll, sustained sub-mediocrity, and recent 101-loss season — are what the Reds could be if this most recent teardown was undertaken without a plan to get back on top. The farm system now ranks highly — with top prospects like Oneil Cruz suspiciously still spending time in the minors — but fans have a clear sense of who is to blame.

Four years ago, over 60,000 people signed a petition imploring owner Bob Nutting to sell the team. Last year, Pat McAfee lent his voice to the cause. Those were hopeful times.

Their attendance has been in the bottom five since 2017, and this season it’s lower still. With an average crowd size below 12,000 through the first month of the season, attendance in Pittsburgh is down more than 35% from 2019 (the last truly normal season).

Christy McElhinny, a 33-year-old from Bridgeville, Pennsylvania, is a former season ticket holder who loved the Bucs so much she and her husband took their wedding photos at PNC Park.

“Before I would schedule my dinner plans, my workouts, my vacations, etc. all around attending as many games as I could,” she wrote.

That kind of commitment doesn’t just disappear and she doesn’t plan to fully boycott the team this summer. Now, though, she’s just apathetic. “So I only go if I don’t have anything better to do.”

“I always think fans can and should be heard. I think attendance is a perfectly reasonable way to show this,” she said about whether a boycott or wholehearted support would go further to benefit fans’ cause. “I, however, have little faith that that attendance actually means much to our ownership.”

Orioles — ‘I honestly think the O’s are (finally) on the right track’

The Orioles lost over 100 games the past three full seasons, and yet the city seems to have hope. This year, their attendance is up slightly, currently sitting at 22nd in baseball, the highest of these four teams.

“I believe that where the Orioles are, in comparison to the other teams you listed in your tweet, is an entirely different position,” wrote Dan Krotz of Damascus, Maryland. He acknowledged that the rebuild was brutal, “but we’re at a point now where we’re coming out of it and can see the light at the end of the tunnel, so to speak.”

This year for the first time, Krotz bought a season-ticket plan. It was affordable, and he has faith in general manager Mike Elias, who was hired away from the Astros in a bid to replicate their successful rebuild after the 2018 season. He has preached patience while promising bluntly a long but ultimately productive process. And some of that has been borne out in the organization’s successful restocking of its pipeline.

“I don’t begrudge fans their choice, but I’ll still attend games even while frustrated with the overall direction of a team,” said 44-year-old Dennis O’Brien, who lives in Rochester, New York, but has trekked to Baltimore to see them since the ‘80s, weathering all the bad years in recent decades. “I honestly think the O’s are (finally) on the right track so I don’t feel conflicted this year, even if they still stack losses.”

But even fans that are more skeptical of the front office — and in another year with MLB’s lowest payroll after an offseason in which the team spent less than $10 million combined on free agents there are ample reasons to be getting restless — are finding bright spots in the Orioles’ on-field product recently.

“Last year, I was treated to an incredible season from a breakout star in Cedric Mullins, the growth and development of a young and talented player in Austin Hays, and watched the resilient story of Trey Mancini,” wrote Connor Guercio, 25, of Pasadena, Maryland. “If I completely stopped going to games in protest of what [executive vice president] and GM Mike Elias is doing in terms of roster construction, I would have missed out on all of that.”

The Angelos family that owns the Orioles is, naturally, the source of ire among those who can’t stomach supporting them. Jim Riley, 40, said that what they’ve done with the team “is a disgrace.”

“My money seems to be going to the owner and not reinvested into the team. Hard to create a loyal fan base in this environment,” he wrote. “The old school fans will come back at the drop of a hat when the team starts winning again, but I think they’ve failed to grow with the young fanbase.”

Fans fear what a disengaged market might mean for the team they still love. If ticket sales are a way for them to communicate with ownership, a lack of attendance could be interpreted as an impassioned rebuke. Or as disinterest.

“I personally worry when it comes to not showing up to games as a form of protest mainly because the worry then becomes, what if the team relocates?” Guercio said. “I think we see this now with the Oakland Athletics and them eyeing a potential new home in Las Vegas in correlation to historically low attendance numbers.”

A’s — ‘Being an A’s fan was starting to feel like a bad Lifetime movie’

The A’s stadium situation is too complicated to detail in a story about anything else. But for years now, fans there have been rooting for a team that has managed to turn small payrolls into frequent playoff appearances under a growing specter of impending relocation.

“Being an A’s fan was starting to feel like a bad Lifetime movie,” Willis of Concord, California, wrote — threats to leave followed by charming success; teardowns; a hope that sufficient love, loyalty (and money) will convince them to stay.”

The team’s lease at the Coliseum runs through only 2024 and extending it is essentially not an option given the state of the stadium.

“Oakland’s in a critical situation,” MLB commissioner Rob Manfred said in October. “We’ve had to open up the opportunity to explore other locations just because it’s dragged on so long. Frankly, in some ways we’re not sure we see a path to success in terms of getting something built in Oakland.”

That ominous allusion was accompanied by the franchise’s explicit exploration of following the once Oakland Raiders to Las Vegas. More recently, the plan for a new park at the Howard Terminal site at the Port of Oakland — first discussed back in 2018 — has seemed to pick up steam. But the threat of leaving lingers over a season that they’ve started 14-19.

“The move is 100% the reason I won’t go to the Coliseum this year,” wrote John Baker, 43, an A’s fan living in Brooklyn. “I’d definitely be more excited about Cristian Pache if I thought the A’s would still be in Oakland in two years.”

He said he’ll go to games when the team comes through New York — it’s a way to cheer on the players without enriching the owners — but won’t spend any money on A’s tickets or merchandise. “It feels like direct action even though it’s just a drop in the bucket.”

“It’s not like this is the first time the A’s have low attendance,” he wrote. “But it does feel like the first time that the team has completely alienated their fans.”

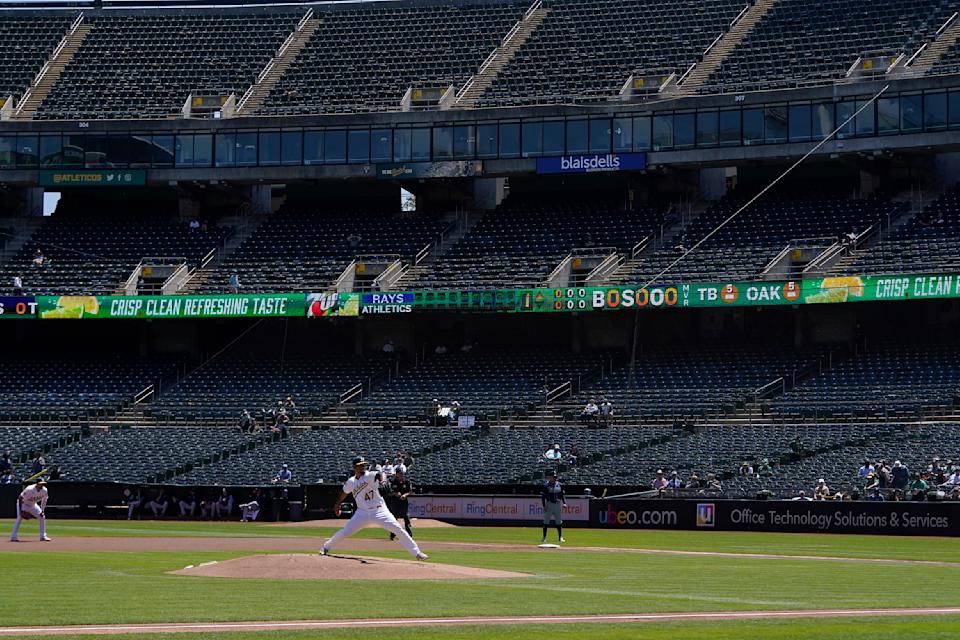

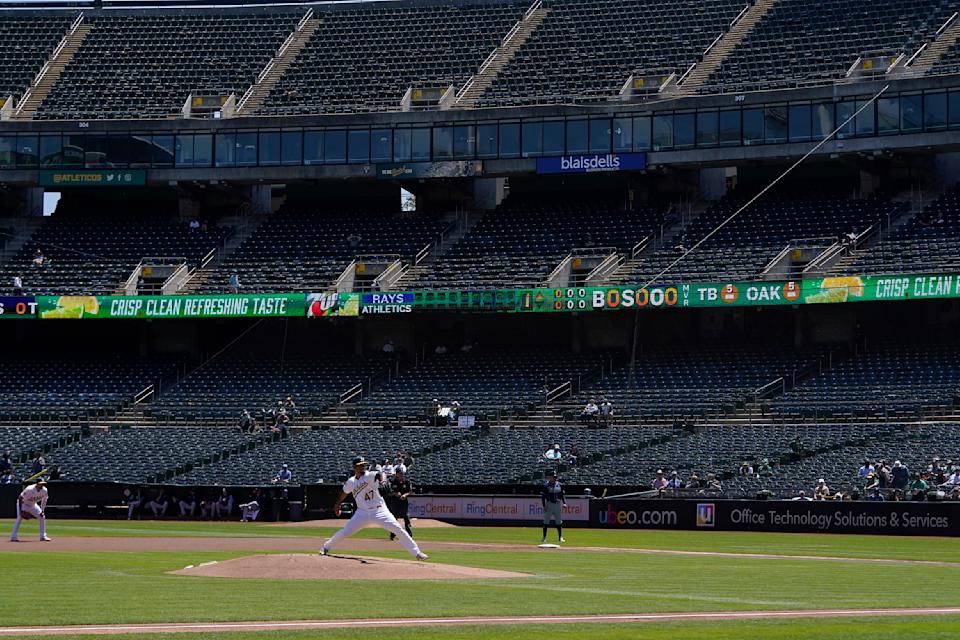

It’s early in the season, but the numbers are grim. The A’s are the only team with an average crowd less than 10,000. They’ve seen the most precipitous drop off in attendance of any team since 2019, and even diehards are losing interest.

“People have talked about the A’s going here or there for so long I just have a general malaise about the whole situation,” wrote 35-year-old Andrew Patrick.

He lives just 20 minutes from the Coliseum, but hasn’t gone to any games this season. It’s not all the relocation talk, per se. The experience just isn’t worth it anymore.

The A’s emerged from MLB’s lockout ready to sell, and ended up trading three of their best players — Matt Olson, Matt Chapman and Chris Bassitt — to keep their payroll second lowest behind Pittsburgh and load up on prospects. The lack of competitiveness from the outset and the fact that amenities at the Coliseum seem worse even than before have eroded his commitment to the team.

“I used to attend fanfests and all sorts of events and made A’s fandom part of my identity, which drove me to hold season tickets and buy merchandise,” Patrick said. “Now, though, the relationship is so much more commercial that I have no drive to do so.”

The A’s fans I heard from seemed particularly disillusioned and felt particularly unheard.

“It’s not like John Fisher is listening,” Baker said, “I don’t think he cares if nobody goes to the games, or if he sells out every game.”

“I don’t think there is anything an A’s fan can actually do, attendance related or otherwise, to influence events toward our desired goals as fans,” wrote Ricky Dunham, 41, of Murrieta, California. “Mr. Fisher has his own goals and he’s going to respond to events in whatever manner supports those goals. So if we don’t attend games, he gets to cite low attendance and talk relocation and we lose. If we do attend games, he makes more money, nothing changes, and we still lose.”

And, so, for the most part, they don’t attend games and photos of empty seats at A’s games will circulate on Twitter — because the product is bad, the future uncertain and the prices are disproportionate with the experience. Or because some fans still have faith that a soft boycott might make a difference. But not because the A’s don’t have fans to begin with.

“The Coliseum is my happy place. It’s basically a second home. I’ve gone to games there my whole life. It would kill me to have to go less because of the price hikes and it kills me even more to not go at all in protest. But I’ve been taken for granted and taken advantage of by John Fisher and his ownership group for far too long, enough is enough,” wrote Willis, whose ardent email was at the start of this story.

“All those A’s games with announced attendance less than 10% of capacity? That’s not because the East Bay doesn’t love baseball, because we do.”