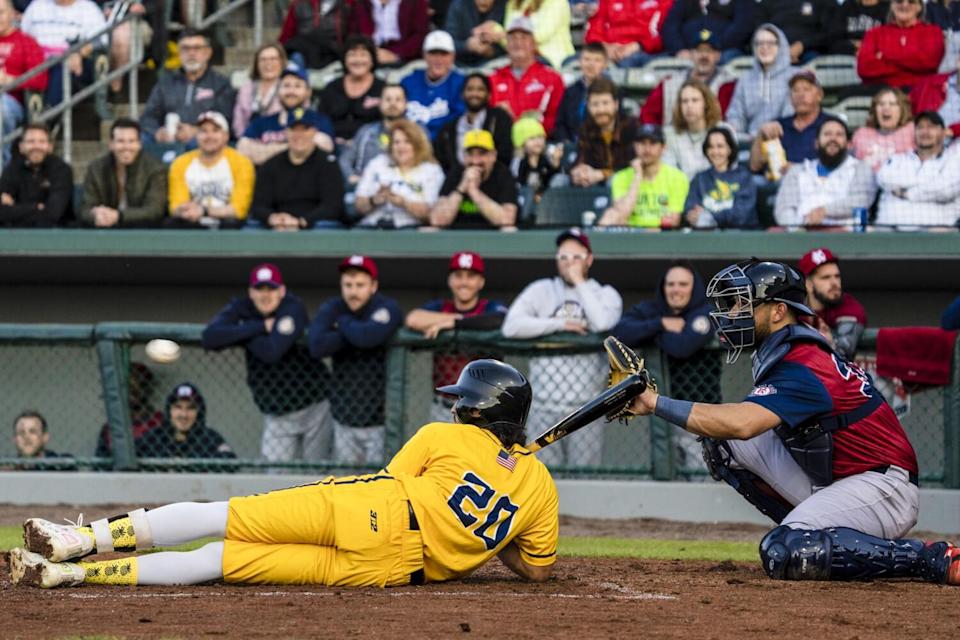

The umpire calls ball four and all hell breaks loose.

Rather than trotting to first base, the batter breaks into a sprint and doesn’t stop, rounding the bag at full speed. The catcher jumps up and throws to the shortstop, who tosses to the second baseman.

The crowd is roaring now as fielders keep flinging the ball from one to another. Amid this chaos, the runner digs hard and slides into second. Safe.

Wait, didn’t this all start with a walk?

Baseball gets flipped on its head when the Savannah Bananas hit town. The Georgia team, which normally plays in a collegiate summer league, spent the past three months barnstorming the country for a series of exhibition games, testing a radical new version of the sport.

“Banana Ball” moves at breakneck pace. There are no bunts, no visits to the mound and a two-hour time limit. If someone in the stands catches a foul ball, the batter is out. And walks? The otherwise mundane play continues until every fielder — even outfielders — touch the ball.

“A lot of moving parts,” Bananas first baseman Dan Oberst says. “You can’t blink or you’ll miss what happens.”

Eccentric rules are only part of the circus atmosphere. The first-base coach dances and the team celebrates home runs by racing into the stands for high-fives. When the Bananas are in the field, they might launch into a brief, choreographed routine between pitches, spinning and slide-stepping like the Four Tops in cleats, only to resume play as if nothing happened.

Team owner Jesse Cole serves as ringmaster, darting around in a yellow tuxedo and top hat, leading sing-alongs — Woah, livin’ on a prayer — and judging toddler races between innings. Lanky and frenetic, Cole is equal parts P.T. Barnum and Walt Disney, with a bit of “Saturday Night Live.”

“We’ve always been very clear about our goal,” he says. “We exist to make baseball fun.”

His team looks like another Harlem Globetrotters at first glance, but the competition is genuine and there is something potentially important at work.

Major League Baseball has seen its attendance and television ratings steadily drop amid concerns about sluggish play. Changes, including a pitch clock and automated strike zone, could be on the way.

The Bananas are a step ahead, packing ballparks throughout the South and Midwest, transforming themselves into a national brand with highlights on ESPN and 2.5 million TikTok followers. MLB executives say they are watching for any ideas that might make their game more “fan-friendly.”

“I love what they’ve done,” says Mark McKee, chief executive of the minor-league Kansas City Monarchs, who recently played the Bananas. “And it’s going to just keep growing.”

Still, in a sport that clings so desperately to tradition, purists will grumble. Is this really baseball? Is it bad for the game?

The first pitch at Legends Field in Kansas City, Kan., is hours away but hundreds of fans have already gathered in the parking lot. Though most of them have never seen the Bananas in person, have only clicked on highlights, they crowd around a merchandise table to buy yellow-and-blue caps, shirts and jerseys.

Watching from afar, Cole grins: “What do you think?”

There is much to do before the gates open for the first of two games against the Monarchs, the owner scurrying from one place to another, getting everyone ready. At 38, he has brought a crew of 120 — what kind of small-time franchise does that? — including a pep band, a princess in a ballgown and a team magician.

“This is the biggest test we’ve ever had,” Cole says. “Can this work?”

His quest to remake baseball began with disappointment, a shoulder injury that ended his college pitching career and dashed any big-league dreams. After graduation in 2007, he tried coaching but grew bored.

The Gastonia Grizzlies of the Coastal Plain League, a summertime showcase for college players, needed a front-office intern; it turned out that Cole’s energy and personality suited the work of cold-calling local businesses, drumming up community support. When the general manager quit, ownership asked the 23-year-old to take over.

If that sounds impressive, Cole sets the record straight.

“Worst franchise in the country,” he says. “They had only $268 in the bank.”

Instead of learning from fellow baseball executives, Cole studied Barnum, Disney and the late Bill Veeck, an outlandish big-league owner who once held a “Disco Demolition Night” that sparked a riot at Comiskey Park.

“Do the unexpected,” Cole says. “I started announcing things and I had no idea how we would do them.”

Flatulence Fun Night. A salute to underwear. Offering Pres. George W. Bush a paid internship upon his leaving the White House. But any team could dream up quirky promotions — Cole needed more.

Barnum preached about keeping customers happy. Disney used the word “Dare” to encourage constant innovation. Even after the Grizzlies boosted attendance and revenue, Cole kept experimenting and, in 2014, stumbled upon a new opportunity while vacationing in Savannah with his wife, Emily.

The couple attended a single-A game and fell in love with the ballpark. The brick façade and graceful arches. A field where Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle and Jackie Robinson once played. They could not fathom why the stands were empty on a warm summer night.

“I mean, a couple hundred people,” Emily recalls. “And the stadium was so majestic.”

Minor-league baseball teams tend to come and go, some affiliated with major-league franchises, others independent. Cole told the Coastal Plain League that if Savannah ever became available, he wanted a team there. A year later, the existing franchise threatened to move unless Savannah built a new stadium.

“The community wasn’t behind it,” says Joe Shearouse Sr., a former city official. “Just wasn’t going to happen.”

Cole had his chance.

The situation was hardly ideal.

Savannah’s rocky history with minor-league ball dated to 1940 when a hurricane destroyed its original ballpark. Even after a local alderman spearheaded the construction of Grayson Stadium, more than a dozen teams and affiliations passed through over the years.

When the Sand Gnats left after the 2015 season, there wasn’t much appetite to try again.

“People in town were really blasé about it,” says Jim Morekis, founding editor of The Savannahian alt-weekly newspaper. “It was not a community thing. There was not a great track record.”

Cole, a fast-talker given to interrupting himself mid-sentence, blurting out one idea or another, pleaded his case, persuading Shearouse to attend a Grizzlies game on a church promotion night.

“They had had the place packed. They had all these choirs singing,” Shearouse recalls. “I was thinking, man, these people are having a wonderful time.”

With approval from the league and a ballpark lease from the city council, the Coles raised money to launch a new franchise, hiring employees and assembling a roster of college players for the upcoming summer season. But there were other challenges.

For all its stateliness, Grayson Stadium had fallen into disrepair, no working phones or plumbing, ceiling tiles missing. The couple nearly went bankrupt those first few months, unable to sell more than a handful of season tickets. Desperate to be noticed, they held a contest to name the new team and selected maybe the least-popular submission.

This has to be a joke, a Savannah resident posted on social media. Another wrote: The Bananas deserve every bit of teasing that they have been getting around the sports world.

No one could see what Cole saw. The logo — a cartoon Banana with bat cocked, lips twisted in a grimace. Bright yellow uniforms and a costumed mascot named “Split.” An elderly cheer squad called the “Banana Nanas.”

“It was a no-brainer,” he says. “We saw the brand.”

One more thing: If fans were angry, they were paying attention. It was like the Barnum adage.

There is no such thing as bad publicity.

With the Kansas City crowd still milling outside, a yellow-clad pep band marches into the parking lot, trumpets and saxophones blaring, players in uniform following close behind. While other teams take batting practice, the Bananas focus on what they call the “H3”: handshakes, high-fives and hugs.

For all the stunts and brash marketing, the franchise has found a crucial ingredient that traces to Barnum’s dictum about treating customers well.

There is a sweetness to the way players hand out programs and mingle with fans before games. Dakota Albritton, who pitches on stilts, talks with people waiting for a port-a-potty. Catcher Bill LeRoy not only gives autographs, he asks kids to sign his wristband. The team joins the band for a spirited version of the 1960s hit “Hey Baby.”

“When you show up somewhere and have players interacting with you the whole time,” Oberst says, “I think that’s a different experience.”

Fans rush inside when the gates finally open, finding their seats, eager for the entertainment to begin. Princess Potassia sings and Cole presides over the first of many contests.

Down on the field, the team performs an intricate warmup — picture the Globetrotters’ passing circle with mitts — then gathers at home plate. Each game, a “Banana Baby” is enlisted from the stands, dressed in a costume and held aloft like Simba in “The Lion King.”

Maceo Harrison, the dancing first-base coach, always upbeat and quick to laugh, pulls a few players aside to rehearse a routine they will perform that night.

“At first they’re a little uneasy so I have to start simple, you know, step-touch,” says the dance instructor who had to learn baseball on the fly for this job. “Now you’re starting to see a little smile here and there, but we’re not doing anything spectacular.”

As game time draws near, the Bananas must “flip the switch,” as they call it.

“It’s Broadway meets baseball,” says Eric Byrnes, a former major leaguer who manages the team in faux leopard skin and a tartan kilt. “None of this works unless we play the game. If we’re not catching the baseball, throwing strikes, if we’re not putting the ball in play, it’s not entertaining.”

Baseball is like a hot dog stand. At least Cole sees it that way.

The Bananas eventually charmed Savannah, filling Grayson Stadium’s 4,000 seats for every league game — unconventional environment, standard rules — but there was a problem. Snapping photographs of the stands each inning, Cole could see much of the crowd heading home early.

“We were amazing at the condiments, the mustard, the relish, the ketchup, the promotions, the dancing,” he says. “But the hot dog — baseball — still needed work.”

It was no secret the sport was lagging behind a quick-twitch world, young fans loath to sit for games that stretched past three hours. Cole and his staff started playing “What if?”

“We looked at every boring play,” he says. “And we got rid of it.”

They revamped walks and foul balls and decided not to start a new inning after 1 hour and 50 minutes. Batters are given a strike if they step out of the box but have the option of stealing first on any pitch that skips past the catcher.

“Banana Ball” is scored like match play in golf: The team that gets the most runs in an inning receives a point for that inning, the win going to whoever has the most points at game’s end. For extra innings, the defense gets a pitcher, catcher and one fielder. If the batter puts the ball in play, they have to chase it down and throw home before he crosses the plate.

How is this going to work? Oberst recalls thinking. Players gave it a try because they trusted their owner, the guy who danced and clowned for them every night, festooned from head to toe in yellow.

“If you’re going to talk the talk, you have to walk the walk and I don’t think anybody does that more than Jesse Cole,” pitcher Kyle Luigs says. “He’s not going to ask us to do something that he wouldn’t do.”

The Bananas held trial runs against college and neighboring teams, then recruited an opposing squad, the Party Animals, like the Globetrotters and the Washington Generals, except the Animals could try to win.

“Banana Ball” hit the road in 2021 for two games in Mobile, Ala. Players were awed by the sellout crowds of 3,500.

“They said it was the most fun they’d had in baseball,” Cole recalls. “I knew if the players loved it, the fans would love it.”

This spring, an expanded tour began at home in early March, continuing through Florida and Alabama, with play growing crisper each game. Pitchers worked fast, batters stayed alert to run on wild pitches and the defense improved on walks, whipping the ball around, tagging out runners at second.

Ever the marketer, Cole invited the iconoclastic — and 75-year-old — Bill “Spaceman” Lee to join his bullpen. The former Boston Red Sox all-star liked what he saw.

“This is saving baseball from itself,” Lee says. “Look at the fans’ response, look at the way the kids are showing up.”

By the time they reached Kansas City for the tour finale, players had learned something unexpected about what they call “BananaLand.”

“Most people are usually pressing to play well, thinking about their performance a lot,” Luigs says. “But if you can get out of your comfort zone and do something to get your mind completely off baseball … you’ll play better.”

As their game-day production grew more elaborate, the Bananas needed to be something more than a baseball operation.

“Jesse and I did a case study on ‘Saturday Night Live’ and what their schedule looks like,” says Zack Frongillo, the entertainment director. “We tried to figure out what works for our team.”

Staff gathers for an “Over the Top” meeting each Monday, brainstorming five or more new bits for the coming weekend. Frongillo writes a script and reconvenes his crew for a Wednesday table read to test the material. Friday mornings are for rehearsal and blocking on the field, making sure social media cameramen have the best angles.

In “BananaLand,” the field is known as the “stage” and auxiliary performers — the mascot, the magician — are “cast members.” There are recurring skits such as the “3-2-2,” the third-inning moment when players dance between pitches, and the “4-1-1,” a fourth-inning bit that has umpire Vincent Chapman — a cast member flown in from Texas — emerge to dance the robot or maybe do the splits.

The Kansas City games are particularly nerve-wracking, the first time Savannah will face a minor-league team that has no experience with all of this. During rehearsal, Frongillo never stops moving, barking commands into his headset, checking and re-checking his script. When the players keep missing their marks for a warmup drill, the veteran LeRoy steps in: “Pay attention! You have to be where you’re supposed to be or it’s screwed up.”

The Monarchs watch from their dugout bemused. Cole asks to speak with them.

“I know you guys are wondering what’s about to happen tonight,” the owner says. “There are a lot of unwritten rules of baseball we don’t really play by, all right? We play by having fun.”

The mention of singing and dancing is met with stern looks, pressed lips. The Monarchs roster includes Matt Adams, a former St. Louis Cardinals first baseman, a bear of a man known as “Big City,” who is recruited for a mock pregame weigh-in, like at a prize fight. He doesn’t seem eager.

The response is even cooler when Frongillo asks the Monarchs to learn a TikTok dance. Kansas City first baseman Fernando Esquivel says later: “It’s different. We’ve literally never played that type of baseball.”

There is much at stake for a Bananas franchise looking beyond the confines of summer college ball. With a good showing in Kansas City, Cole says, “it’s going to be game over. We’ll be playing other teams all over the country and all over the world.”

This is what the Bananas and their owner have created — a formula that people seem to understand immediately, simple and joyous.

It shows in the way fans arrive early to Legends Field, smiling even before they pass through the black iron gates. It shows in the way they sing, clap and cheer for more than an hour before the first pitch.

“I like baseball games but, for me, they’re just a little slow,” says Will Denton, who brought his family three hours from East Missouri. “This thing is like sensory overload.”

Even the Monarchs come around, Adams flexing his muscles and sneering at Bananas pitcher Collin Ledbetter during the weigh-in. When it is time to dance, the home team streams out of its dugout to take part. Even the pitcher and catcher, warming up on the field, pause to wave their hands in the air and spin.

“Having a little fun,” Esquivel says. “Actually looking like we are enjoying the game of baseball like we did when we were kids.”

The Bananas worry about facing a talented minor-league squad that won a title last season, concerns that prove valid when the Monarchs score six runs in the first inning. But the match-play system — which awards only one point for that outburst — provides some cushion for Savannah to settle down.

There are several exciting walks, a fan catching a foul ball and the umpire’s fourth-inning cameo. Lee earns a big cheer for pitching a scoreless fifth, after which the Bananas venture into the stands, handing roses to women for Mother’s Day.

The baseball is entertaining and competitive, but as Princess Potassia sings, “who cares if we’re winning or losing, our show will still go on.” The Monarchs earn a 3-2 victory the first night; the Bananas win by a point the next.

“There is something special going on in Savannah,” says Morgan Sword, an MLB executive vice president. “They are celebrating the game of baseball in a unique way and fans are embracing it.”

If nothing else, Cole sees enough over the weekend to think next season’s tour could be bigger, involving more minor-league teams (a California visit is highly possible). He believes the major leagues can learn from his experiment.

“They are never going to do a fan catching a foul as an out,” he says. “But batters not stepping out of the box — why can’t that happen? There are all these little things we’re doing to speed up the game.”

And to keep fans in their seats. Legends Field remains full and raucous from the first pitch to the last. Much of the crowd lingers in the parking lot afterward as players, still sweaty and dusty in their uniforms, return for another visit.

The band plays pop songs, Harrison dances and people line up to snap photographs with Cole. Fans might complain about three-hour MLB games but, on this night, they stay twice as long.

Nearing 10 p.m., the Bananas line up arm-in-arm and, accompanied by tuba, serenade the crowd with a heartfelt if slightly off-tune rendition of “Stand by Me.” When the goodbye song ends, everyone — players, coaches, fans — form a giant huddle for one last cheer.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.