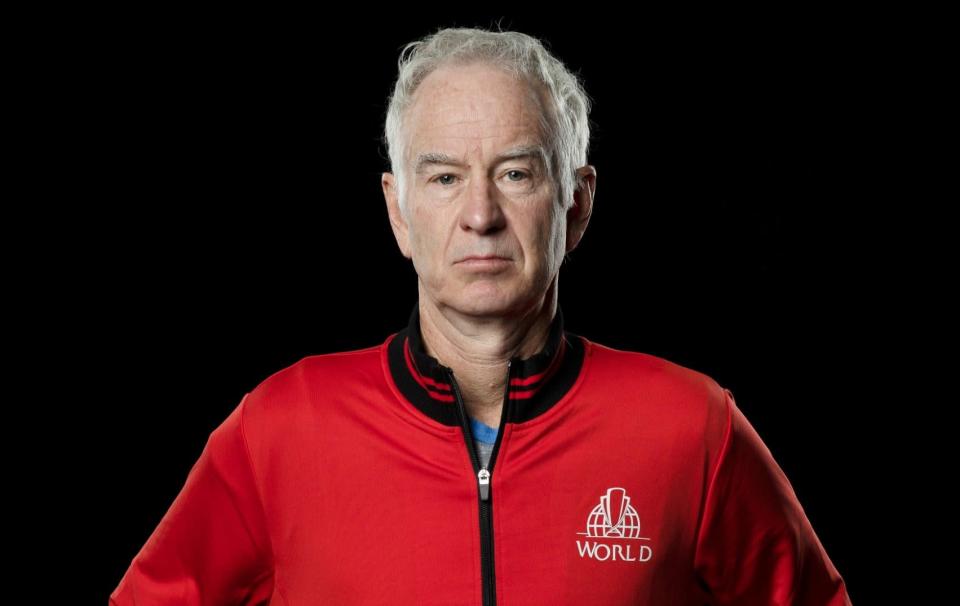

As the curtain fell on a fraught, complex Wimbledon, John McEnroe was not among those making a beeline for the champions’ ball. Famously, he sent the All England Club into apoplexy when, after his cathartic triumph over Bjorn Borg in 1981, he boycotted the black-tie event. It is comforting to hear that, 41 years on, he harbours not the slightest regret about it.

“Chrissie Hynde and her band were coming over to my place, Draycott House in Chelsea,” he reflects. “It was low-key, just the way I wanted it, with no paparazzi. I asked myself: ‘Why the hell would I want to go to some stuffy dinner and hang out with a bunch of people three times my age?’ I did ask my dad if I should make an appearance. He said: ‘I don’t know.’ And so I thought: ‘Forget it, I’m going to hang out with my friends.’ The next morning, I walked out to my car, thinking all was well and good. All of a sudden, 15 cameras were popping in my face.”

McEnroe, 63, is today such a fixture of the Wimbledon furniture that he turns up to Sue Barker’s farewell in a green suit and pink shirt, blending in perfectly with the flowerbeds. But there remains a side to his character that is incorrigibly rock ‘n’ roll, where name-dropping Hynde and The Pretenders is a natural impulse. Even when hopping between BBC and ESPN commentary booths on the final weekend of the Championships, he found time for a cameo on the British Summer Time stage in Hyde Park, playing guitar with Pearl Jam on Rockin’ in the Free World.

It is a thrilling throwback to the days when, as the original enfant terrible of tennis, long before anyone had heard of Nick Kyrgios, McEnroe could somehow combine winning seven major titles with an early Eighties lifestyle of shameless New York excess. “It was a hell of a time, I will say that,” he smiles. “It’s nice to feel like you can have your cake and eat it, too. It can catch up to you, more quickly than you realise. People have only understood recently that opiates are an absolute horror show. Then, you didn’t know about these drugs – their use was a lot more frequent. When I walked off court, people would hand me a beer. Now, players jump straight into an ice bath.”

For McEnroe, the ageless wonder of Novak Djokovic, now a 21-time slam champion at the age of 36, almost defies comprehension. The Serb’s seventh Wimbledon triumph extended a sequence where, since the 2005 Australian Open, 59 of 69 majors have been won by Djokovic, Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal.

“You couldn’t make this up in your wildest dreams,” he says. “These guys have done something that no one anticipated happening. We were happy still to be playing at 30. I made it until two months before my 34th birthday and I thought I was pushing it, that I was hanging on too long. But these guys are still playing as well as they’ve ever played. That’s the part I don’t understand. I always use the phrase: ‘The older I get, the better I used to be.’ This started in my late 20s, for God’s sake. So, I have to look at the Big Three and enjoy it. We all do.”

Djokovic might be three times as decorated as McEnroe in the slam stakes, but does he truly have more fun? When you watch the riveting documentary McEnroe, released in cinemas on Friday, you start to wonder. While the film does not sugar the messier elements of his life – the chaos of his marriage to Tatum O’Neal, the child Oscar-winner who later became a drug addict, or the strained relationship with his father, John Snr – it also finds an irresistible mystique in his restless, brooding nature. A recurring motif is the sight of McEnroe on a night-time walk through Manhattan, steam rising from the manhole covers as he waits for the sun to rise again.

“There’s a grittiness about New York, and that represents my personality pretty closely,” he explains. “All through high school, I would ride the subway, experiencing life the way a typical New Yorker would. Now you don’t go five minutes without knowing where your kid is. But the energy of New York, it meant that I wasn’t just in this elitist bubble – which tennis is, too much. When I first travelled to London, I did see a little of the King’s Road and the punk scene, but mainly, I remember being shocked at how polite and well-behaved everyone was.”

‘Can we talk about tennis, not who my girlfriend is?’

The mysteries of the English class system also bewildered him. After 40 years spent transforming himself from a super-brat into an establishment figure in tennis, is he still struck by these? Or has he come to accept such eccentricities? “I would say both. I still don’t understand it, but it’s above my pay grade. I do think that there’s still that whole class thing going on.”

One certainty about McEnroe and Wimbledon was that the old codes of decorum never stayed intact for long. While everyone remembers his hectoring of umpires and his contempt for strait-laced Wimbledon protocol, the antipathy he aroused even spilled over into the press room.

In 1981, when one British reporter dared to ask McEnroe about his then girlfriend, Stacy Margolin, long tensions between Fleet Street’s finest and their transatlantic counterparts gave way to a full-blown fist-fight, with Nigel Clarke of The Daily Express standing on a chair to punch downwards. The latest film captures the moment in all its glory.

“It reached the stage where I would say: ‘Look, can we talk about tennis, not who my girlfriend is? That’s not really what I’m here for.’ It was to the point of absurdity. And then, finally, this American journalist I knew a little said: ‘If you keep asking, we’re going to ask him to leave.’ It wasn’t me walking out. The British guy was frustrated. It was funny that it got to that level – I had a good laugh over it.”

One theme that soon emerges about McEnroe is his astounding eye for detail. Whenever he visits Paris, for example, he is acutely disturbed by the memory of losing the 1984 French Open final to Ivan Lendl from two sets up. “Every year,” he admits, “I have a couple of nightmares where it gets into my head.” His second wife, the rock singer Patty Smyth, emphasises his exceptionally acute visual sense, which would enable him to analyse the court much like a chess board.

Was this capacity innate, or simply enhanced through tennis? “That’s a good question. I’m not 100 per cent sure. I used to be quite closed-minded. My brain had always been that of a sports jock. But when my late, great buddy, Vitas Gerulaitis, started taking me to art galleries and showing me how to play guitar, it opened up a whole new world to me.”

It is an illustration of McEnroe’s significance as a cultural figure that he even earns a tribute in the biopic from Keith Richards. As a player, a commentator and a friend to the gods of rock, he has never lost his ability to captivate. On the BBC, he retains that rare talent for making even the most unappetising contest seem a must-watch – a gift that his arch-rival Bjorn Borg never emulated.

“Bjorn was calling my final against Chris Lewis for NBC, at Wimbledon in ’83,” he laughs. “Chris was unheralded, unseeded. The presenters asked Bjorn: ‘What do you think is going to happen in the match?’ He just said: ‘Chris Lewis has no chance.’ You do want to keep people interested. A little entertainment can go a long way in a one-on-one sport like tennis. Believe me, we need more of it.”

McEnroe was devastated by the suddenness of Borg’s retirement from tennis, aged 26. “An absolute tragedy,” he declares. It is why he cannot fathom Ash Barty’s decision to step away from the sport at 25, as the women’s world No 1. “It feels like something’s off,” he says. “It just doesn’t seem right to me.” He might earn a fortune today as tennis’ expert extraordinaire, but the road to finding meaning since his days as the undisputed best has been long and tortuous.

“Not many people peak in their career at 25, then try to find a way through to where they can be happier than they were,” he acknowledges, with his usual bracing candour. “All things considered, it was a great way to make a living. But as a player, I ended up never getting back to the same level. That sucked.”

‘McEnroe’ is in cinemas from Friday