[World Cup: Viewer’s guide | Group previews | Top 30 players | Power rankings]

On a steamy summer day in 2006, nervous energy wafted off a field in Zarephath, New Jersey, where U.S. Soccer had convened its most talented 14-year-old boys to brighten the future. They milled about the aptly named Players Development Academy, their host for a week-long training camp. They tugged on cleats, slapped on sunscreen and chugged through drills. And as they did, unknowingly, they became a case study in American soccer’s defects.

They were, in theory, as Under-15 national teamers, among the early candidates to star at the 2018 World Cup. But their coaches noticed, more blatantly than ever before, that they’d arrived with “bad habits,” and “looked tired,” “exhausted,” “totally overplayed,” “stale” and “burnt out.” The coaches huddled that night at a local hotel. They rued regression since their last camp. Charlie Inverso, the goalkeeper coach, suggested they conduct a simple survey. They ran off a few dozen copies, and asked players at their next team meeting: In a given year, how often do you train? And how many games do you play? And how many are “meaningful”?

“And the results,” Inverso says, “were shocking.”

According to four people who recalled the survey, it accurately diagnosed American soccer’s developmental ills. Coaches tabulated answers and sent them off to U.S. Soccer Federation president Sunil Gulati. Gulati remembers the takeaway: Kids were playing as much as, if not more, than they were training. “A lot of youth soccer had the model completely flipped,” Gulati says. As one colleague told him: “It’s like having more tests than classes.” And, on average, according to the survey, only a dozen of the 100-some annual tests — the games — were useful and competitive.

The data confirmed what many influential coaches had already suspected, and became “a tipping point,” says Tony Lepore, a U15 assistant coach at the time, and now U.S. Soccer’s director of talent identification. It fortified a polarizing push to overhaul elite boys soccer across the United States. And 15 years later, many believe, that overhaul is beginning to bear fruit.

The U.S. men’s national team is, by some measures, the youngest in all of international soccer. It will kick off its 2022 World Cup on Monday armed with early-20-somethings currently employed by prominent European clubs. The number of American players in the world’s top five leagues has exploded over the past two seasons, while the average age of those players has steadily fallen, from 27.6 in 2012-13 to 21.2 last season, according to Transfermarkt data compiled by Yanks Abroad.

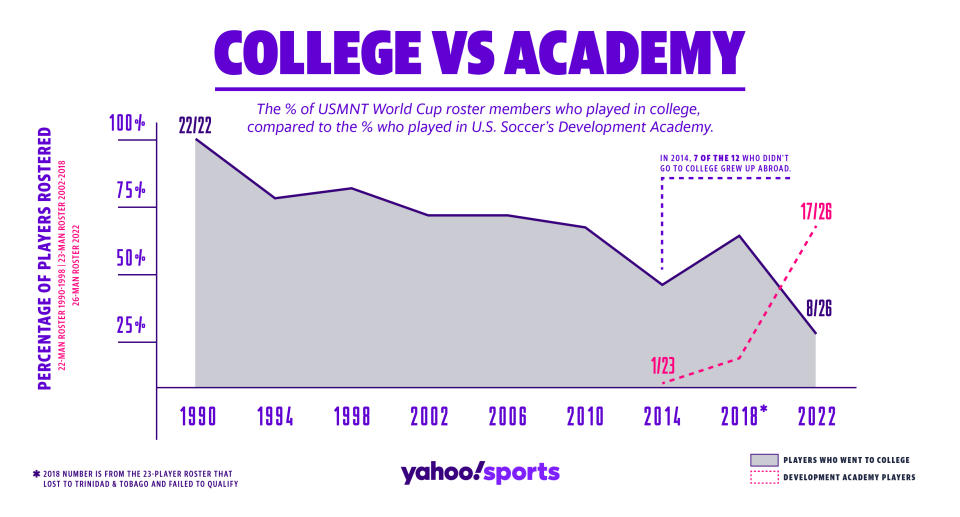

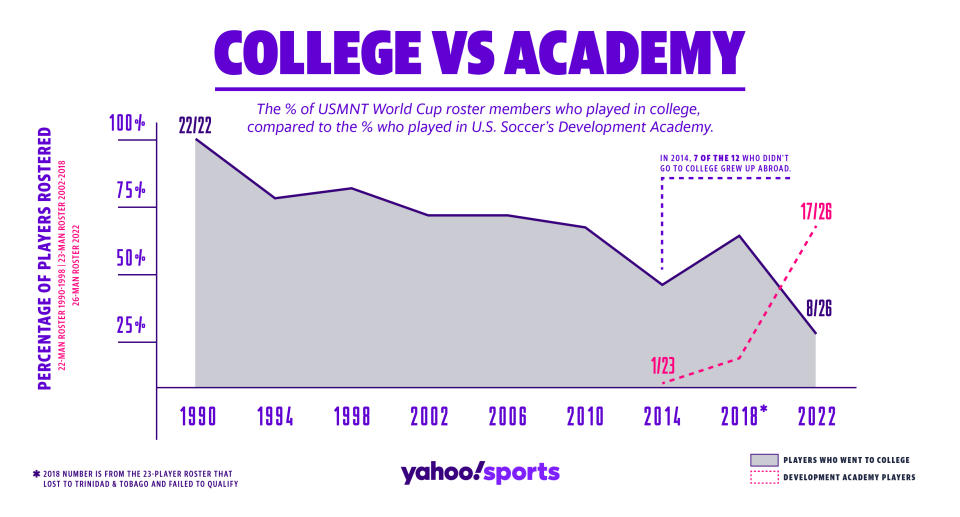

And a majority of those players, for the first time, are not college products nor foreign-born dual nationals. Seventeen of the 26 at this World Cup came through U.S. Soccer’s controversial Development Academy.

The DA, as it became known, is widely cited as the collective birthplace of this USMNT. “It’s not a coincidence,” head coach Gregg Berhalter says, “that all of a sudden we have elite players around the world.” Academy investment, especially by Major League Soccer clubs, is “one of the reasons why we are where we are,” Berhalter said the morning after clinching World Cup qualification.

And it is widely credited with reforming a “broken” system that, for decades, impeded America’s rise in men’s soccer. The reformed landscape, says Alecko Eskandarian, a former player and current development director at MLS, is “night and day compared to where we were 10, 20 years ago.”

But is the reformed system better?

“Well,” says Mike Cullina, a USSF board member and CEO of U.S. Club Soccer — “depends on who’s asking.”

“Did it improve player development?” Cullina continues, reframing the question. “Absolutely. Dramatically so. Was it worth it? I don’t know.”

The ‘Dark Ages’

For decades, the American game remained mired in what Fred Lipka, MLS’ vice president of player development, calls “the Dark Ages of soccer.” There was no stable professional league, and therefore no refined pathway akin to those in South America and Europe. There, amateur clubs funnel top players up a pyramid to pro clubs, whose youth academies prioritize individual development and supply the senior team. In the U.S., on the other hand, most youth clubs were standalone entities, and prioritized whatever could sustain their business model — either recreation or winning.

The elite ones trained twice a week, at most, on weekday nights, in suburbs accessible only by car. Volunteer coaches often ran practices. Some kids spent more time traveling than training. Some sought out multiple teams, or “guest-played” at tournaments. Four- or even five-game weekends were common.

“Players were playing in a competitive environment, but it wasn’t really with a high-performance focus,” says Chris Hayden, the longtime FC Dallas academy director. “It was just, ‘Yeah, you’re a really good player, you’re playing on a really good team, and you guys are winning, so you’re getting some exposure.’”

In a way, Hayden says, “we were sort of developing players by accident.”

The main elite pathway was the Olympic Development Program, an inaccessible tryout-based ladder of area, state and regional teams that fed youth national teams. But in between ODP events and national team camps, kids returned to a fragmented network of volunteer-driven clubs. When a group of U.S. Soccer staffers tried to map out a typical path to the national team, it looked “like a bowl of spaghetti,” Lepore says. It also placed the country’s most potent talents in suboptimal environments, with insufficient competition and coaching, for much of the year.

“You just got the feeling that there wasn’t enough daily improving of the better players,” says Jim Barlow, a former U15 national team coach.

And the penultimate step of the pathway, for many, was college — where, as an unnamed U.S. soccer stakeholder once put it, “players get four years older but not four years better.”

The college system served many USMNTers over the years, especially late bloomers. At least 17 members of each U.S. World Cup squad from 1990-2006 came through it. “But with college,” Lipka says, “you enter in the world at 21, 22, 23 years old.” And in a sport that rapidly elevates teens, “you can’t compete against Europe anymore.”

In the late ‘90s, the USSF tabbed Carlos Queiroz, a Portuguese coach with a wealth of international experience, to conduct a 360-degree review of the American landscape. “Since it is not the collegiate system’s job to produce professional players at the highest level, we must implement a system designed to do just that,” he wrote in his final report, entitled “Project 2010.” He also pointed out that U.S. Soccer “invests time, energy and money into preparation of the youth national teams, but does nothing to improve the competitive system that provides for player development.” And that, he and others believed, was what had to change.

The first fix was a U17 residency program at IMG Academy in Bradenton, Florida. Its first class spit out Landon Donovan and DaMarcus Beasley. But it was a temporary fix for a few dozen kids at a time, for a year or two each, at the tippy-top of the pyramid. U.S. Soccer leaders understood its limits, and grappled with a maddening question: “How do we expand this?”

“Residency was hugely successful,” says John Hackworth, a U17 national team coach from 2002-07. His message to higher-ups was, “We need more of these.”

“And that,” Hackworth says, “is where the idea [for the DA] came from.”

U.S. Soccer wills the DA into existence

In the mid-2000s, Hackworth and other U.S. Soccer honchos dove deep into research on learning and human performance. They worked with Anders Ericsson, the Swedish professor who’d championed the “10,000-Hour Rule.” They studied other fields, like music and education; and leading soccer nations, like Germany and Brazil. They concluded that day after day and week after week of “deliberate practice” was a key to development.

They felt they were doing that at Bradenton. The U17s would train Monday through Friday, then play once on the weekend. When Hackworth would meet with influential directors of coaching from clubs across America, they’d tell him: “What you’re doing here [at residency] is perfect. How can we do this in other places? How can we do it all over?”

USSF officials dreamed of creating 50 or 100 replicas in markets across this sprawling continent. They quickly realized that the only feasible solution was to work with existing clubs. If they could recruit as many as possible to a national league, they could pit top players against one another every weekend — and daily, in 3-5 training sessions per week, which they could mandate as a condition of membership.

So they began campaigning. Hackworth remembers Jay Berhalter, U.S. Soccer’s then-chief operating officer, handing him lengthy lists of names and phone numbers to call and pitch the concept. Kevin Payne, who chaired U.S. Soccer’s technical committee, remembers stumping for the DA in various speeches, referring to it as an “intervention.” Others created visuals based in part on the 2006 survey to demonstrate the old system’s flaws. Along the way, however, they met fierce resistance.

The clubs and their various sanctioning organizations “all wanted to do it,” Hackworth says, “but they all didn’t want to share any part of it.” Some, Payne says, felt “threatened by it.” They worried about losing market share or influence. “We had a couple ugly board meetings,” Payne recalls, because representatives from the U.S. Youth Soccer Association, the largest sanctioning organization, “saw this as a direct attack on their power base.”

So, “ultimately,” Hackworth says, “we at U.S. Soccer just said, ‘We have to do this ourself.’”

“To a certain extent,” Payne agrees, “we had to bigfoot people.” He remembers meeting with other top U.S. Soccer officials and coaches at the Ritz-Carlton in Pentagon City, Virginia, very early in the process. He warned them with two words on a whiteboard: “POLITICAL WILL.” They “needed to understand,” Payne says, “that we were gonna piss a lot of people off with this” — but they needed to follow through with it anyway.

They did, and launched the DA in late 2007, with 62 clubs — some affiliated with pro franchises, some amateur — competing within eight distinct conferences and two age groups. It later expanded to over 100 clubs and six age groups. Those clubs initially trained at least three times per week, and eventually at least four. They quickly became the destination for all elite players, and their tournaments the destination for scouts. They provided scholarships, and professionalized their programs, and played almost year-round — and sparked all sorts of questions about whether the overhaul was worthwhile.

Seeing the light after paying for past mistakes

In addition to governing the league’s 10-month season, U.S. Soccer hired a few “technical advisers” who, in Lepore’s words, doubled as “compliance officers.” They each traversed an assigned region and held clubs accountable to “Evaluation Criteria,” via a five-star grading scale and consistent feedback. The criteria covered everything from “administration” and “facilities” to “training environment” and “style of play” — and contributed to a frequent criticism of the DA: that, rather than molding players, it constructed robots.

The dictation of a specific style, says Cullina, the U.S. Club Soccer CEO, “was asinine, absolutely asinine.”

It stemmed from a Dark Age obsession with winning, which incentivized reactive soccer and stunted skill acquisition. “Defensive approaches at young ages don’t develop players,” Lepore argues. The DA’s goal, he says, was to cultivate ones who could play “in any game model,” including in possession and transition. “And if all you do is play a direct, reactive model, then that’s all you’re gonna be able to do [as a pro].”

So the technical advisers, Lepore admits, “did confront people about style of play.” The DA’s 2010-11 Evaluation Criteria stated that teams “must use Back 4,” and mentioned “play[ing] out of the back, possession” and “transition” as the tactical priorities.

The result, in early years, were stale, homogeneous games. Many clubs adopted 4-3-3 formations. “And they played out of the back,” Hackworth says, “for no other reason besides me or [then-USMNT coach] Bob Bradley or Tony Lepore or somebody told ’em they had to play out of the back.”

That instruction, Hackworth argues, was misunderstood. “You only play out of the back because you want to bring your opponent to you,” he explains. “You want to unbalance them by playing through them or behind them. You’re just trying to create space for yourself.” Over time, he and others say, kids and coaches began catching on and diversifying.

But the broader problem, critics say, is that the kids were overcoached. They learned the nuances of tactical theory, and the split-second decisions that the highest levels of soccer require. But they didn’t learn how to step onto any given field and, in one longtime coach’s words, “go f***ing win a game.”

“And we paid for that in the early [years],” Cullina says. “Our kids could not solve any problems. The environment was sterile. … They were rigid to an absolute fault.”

Various coaches and former players have simultaneously acknowledged the merits of the DA but eulogized the cutthroat competitiveness of the “Dark Ages.” There are, today, fewer do-or-die games, and less collective pride attached to them. The kid who used to fight on behalf of his school or his town or his state now plays merely for his club or himself. Academy games, says Barlow, the former U15 coach now at Princeton University, “are very tactical, and seem to lack some of that juice. … There just seems to be a little bit of that old-school missing.” And there are some who believe that the “juice,” and the “old-school,” are more vital to development than daily training is.

But most agree that the reformed system has, on balance, begun to churn out better, smarter players. It looks and feels a lot more like those in Europe and South America that have produced top pros and World Cup winners. The challenge, then, is maintaining the one aspect of the old American system that was best in class, a soccer-life balance that countless clubs around the world disregard.

“If you go to Brazil, it’s either make it as a soccer player or your life’s over,” says Tommy Wilson, the Philadelphia Union academy director, who has traveled the world and seen this developmental imbalance from all angles. In many countries, he says, for the 99% of boys who don’t make it, “there’s no soft landing.”

Finding balance

Ever since the late ‘00s, thousands of American teens have slogged through school days, then slumped in passenger seats on long drives, then engaged in “deliberate practice” at academies, then returned home with bedtime near, and repeated the routine eight hours later. They’ve eaten meals and scribbled homework in transit. They’ve sacrificed studies and sleep.

“And if you’re in a car eight hours a week,” says Inverso, who also coached at multiple colleges, “you never get a chance to be a kid, for God’s sake.”

The DA prioritized soccer, in some cases at the expense of school or other pursuits. It all but required specialization. It barred its pupils from playing for their high school teams, and incited an explosive debate over the relative value of sporting and social development.

For the top 1% of players, that tradeoff was beneficial. “You’re playing for a reason,” says USMNT winger Paul Arriola, echoing the sentiments of teammates. “Whether … you want to go to college, get a scholarship, go professional, play for the national team — all these different things are dreams and goals that kids and families have. They’re willing to sacrifice what they’re doing, and their time away, to commit to being a part of something bigger, to help them in the end.”

But for the rest? For the ones who didn’t earn a college scholarship? For the ones who craved soccer but also a “normal” life? Or the ones below the DA, whose families had to pay more at younger ages, essentially to subsidize the DA’s free-of-charge policy?

“The expense of the sport and the amount of travel is to the detriment of a vast, vast majority of players,” Cullina says. Neither problem is unique to academies, nor to this era. But in general, Cullina adds, “I think too many kids are having too many bus trips, flights and hotel stays for what they need for their own personal development.”

The DA’s masterminds, including Hackworth and Gulati, acknowledge that the level of commitment it required benefitted some but certainly not all of its participants.

In interviews, a variety of stakeholders argued that this conflict of priorities, between the soccer and the psychosocial, is inevitable.

But in suburban Philadelphia, and at a growing number of MLS academies, innovative leaders are proving that it isn’t.

MLS clubs setting a new American standard

A typical morning for the Philadelphia Union U17s begins with the sun still low and the average teen still groggy. While the U15s lift to bumping hip-hop in an open-plan weight room, or playfully compete in soccer tennis indoors, the defending U17 MLS champs train from 8 a.m. until 10. On a recent overcast morning, surrounded by malls and greenery in Wayne, Pennsylvania, some of the country’s finest prospects attacked a modified 8-v-8 scrimmage and honed the craft that, they all hope, will become a career.

Then they retired to a locker room, donned hoodies and backpacks, grabbed a bite to eat and walked across the street to class.

In 2013, the Union opened YSC Academy, a single-building high school built exclusively to accommodate their youth players. It was investor Richie Graham’s answer to the soccer-vs.-school conflict that so many felt was a zero-sum game. “You really can’t solve elite player development without solving for education,” Graham says. “Those things both matter in our culture. It’s not acceptable to bring a bunch of kids into an elite academy and just say, ‘I’m sorry, you didn’t make it, good luck.’” With an adjacent school, he felt, the Union could promote development while offering a built-in Plan B.

They could, and do, stick five blocks of 40-minute private-school classes in between morning and late-afternoon soccer activities.

They also can, and do, fit individualized film sessions and parking-lot Teqball tournaments in between those classes.

Coaches sit two walls away in offices and analyze drone footage from training.

Qualified instructors teach AP Calculus and U.S. History — but excuse students if, say, they’re called into a U.S. youth national team.

“Of course, they push you to learn,” says Daniel Krueger, a 16-year-old centerback and YSC junior. “But, if you have something very, very urgent, then they’ll be flexible. They’ll meet with you at the end of school. Which is great.”

Other MLS academies, such as FC Dallas’, have partnered with local school districts or found alternate solutions. Real Salt Lake now has its own charter school; other clubs have considered similar setups. But the Union, having studied FC Barcelona and other European models, have set the ever-improving American standard. They’ve sent kids to Duke, Penn and other Ivies. One recent graduate, Wilson says, now works at Goldman Sachs. Another, meanwhile, works in the English Premier League.

Brenden Aaronson, the third-most valuable American player in global soccer, is one of at least 29 Union academy products who’ve signed pro contracts. Several are now members of the senior team that nearly won the 2022 MLS Cup. Others have been sold for millions of dollars, which fund the signings of veteran All-Stars or further investments in the academy. This, precisely, is the model that sustains hundreds of foreign clubs, and it’s the model that savvy MLS franchises have begun to embrace.

“You can literally fund your entire club if you do a good job with youth development,” Hackworth says. “It’s part of the business model of our sport.”

‘The pyramid is complete’: From the DA to MLS NEXT

Major League Soccer kicked off in 1996, and for the first decade of its existence, as it teetered on the brink of dissolution, it invested relatively little in youth development. Its initial dollars went toward stadiums and adequate facilities. It built out technical staffs and rosters. And then, with survival finally assured, around the time the DA came along to offer quality youth competition, MLS clubs began pouring money into academies.

It began with a league mandate and “homegrown player” initiatives, but also leaps of faith. Full-scale academy investment, Graham says, “wasn’t so obvious 10, 15 years ago,” because very few American clubs had ever reaped returns on that investment. But some, like Dallas, believed they could. They hired scouts, performance coaches and counselors. They integrated teens into first-team training sessions. Several current USMNTers remember relishing the chance to reach out and touch their dreams.

“Being able to play in those environments, and know that you wanted to be a part of that someday, I think it was inspiring,” says Jordan Morris, who spent a year in the Seattle Sounders academy. “It helped you grow as a player.”

What many clubs found, though, was that funneling players toward those dreams was difficult. “The bigger issue we recognized,” says FC Dallas president Dan Hunt, “is that we didn’t have the appropriate intermediate step for them.”

Back in suburban Philadelphia, standing in his office, Wilson whips out a marker and illustrates the very same conundrum. He draws the triangular tip of a pyramid, then a rectangular base, with nothing in between. “When I came here at first,” he says, “we had our first team, we had an academy,” — and in the middle, “a glass ceiling.” What the Union needed to do, he realized, was fill the gap between youth and pro, “so that there’s a development continuum.”

Institutional commitments to youth can shrink that gap. Head coaches will usually hand minutes to whoever maximizes their chance to win, unless their bosses preach patience and tell them: “Play your kids.” But words are flimsy; structure is sturdy. What MLS needed, and eventually established, was a platform for reserve or U23 teams. For years, ”too many players were signing homegrown deals, and then sitting on the bench,” Cullina says. Late last decade, more so than ever before, in MLS and the lower-tier United Soccer League, the kids began playing.

In 2020, citing “the extraordinary and unanticipated circumstances around the COVID-19 pandemic” and the resultant “financial situation,” U.S. Soccer shuttered the DA — but MLS essentially assumed control of the entire pyramid and kept the DA’s structure intact. Its takeover, many at U.S. Soccer say, was always the natural and sensible next step. It now runs a DA-style league, MLS NEXT, for many former DA clubs. The MLS academies recruit from other NEXT clubs, and also from the separate Elite Clubs National League. They promote their top talents to MLS NEXT Pro, a new reserve league that prepares players for first teams and beyond.

A decade ago, “we were developing players and there was nowhere for them to go,” Wilson says. “Now, the continuum is continuous. And the pyramid is complete.”

USMNT roster still under construction

And now, virtuous cycles are propelling both MLS and the USMNT, perhaps someday toward the upper echelons of the globe’s most global sport. FC Dallas, for example, has produced players that drove it to the MLS playoffs. But it has also sold Ricardo Pepi, Chris Richards, Reggie Cannon, Bryan Reynolds and Tanner Tessmann for some $40 million, and reinvested that money to accelerate the cycle.

Those academy graduates, meanwhile, along with colleagues produced by a half-dozen other U.S. clubs, are starring in Europe, raising the profile of American men’s soccer, and implicitly encouraging European clubs to send more scouting resources and transfer fees across the Atlantic — which, in turn, encourages more academy investment from MLS owners.

Initially, those European clubs were drawn to the U.S. market by commercialism. But now, Americans and Europeans both say, their motives are evolving. Now, the youth showcase tournaments once abuzz with college coaches are welcoming European scouts. Now, when U.S. Club Soccer hops on a call with partners at Spain’s La Liga, “they are interested in talent identification,” Cullina says.

“The quality of the [American] players increased significantly over the last five or 10 years,” Bayern Munich academy chief Jochen Sauer told Yahoo Sports in 2018. Many believe that it will continue increasing, and that the country’s developmental systems are “just scratching the surface.”

“There’s gonna be a lot more talents coming out of the Philadelphia Union academy,” Aaronson said in May with confidence. His younger brother, Paxten, is one of them, and will soon head to the Bundesliga. “It’s only starting now,” Brenden said. “And even in the whole country, academies are getting better and better.”

Whether the ultimate goal, World Cup success, will materialize in 2022 remains uncertain. The USMNT’s roster, shaped by this overhaul and the “Missing Years” that preceded it, remains inexperienced and under construction.

But the future, most agree, is bright. The failure to qualify last time around — with a roster featuring only four DA alums — was startling. But amid the furor that followed, longtime Bayern Munich youth coach Sebastian Dremmler told Yahoo Sports: “It does not matter.” Because the grassroots repair had long ago started.

“The U.S. market is unbelievable, very good right now,” Dremmler said in 2018. “The programs are better and better. … We will see the final result in five to 10 years.” In 2026, he said, “you will have a very strong national team.”