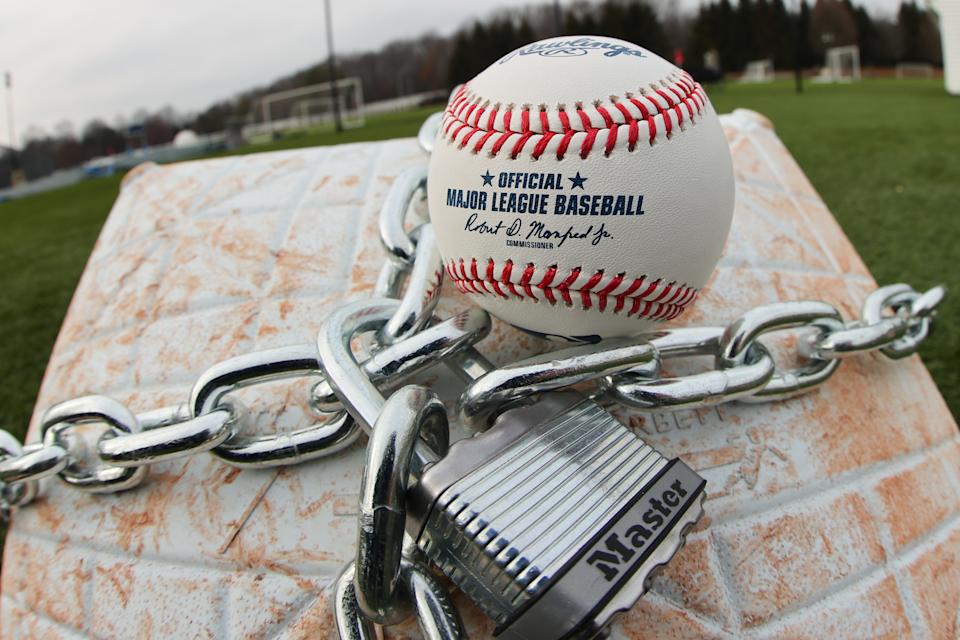

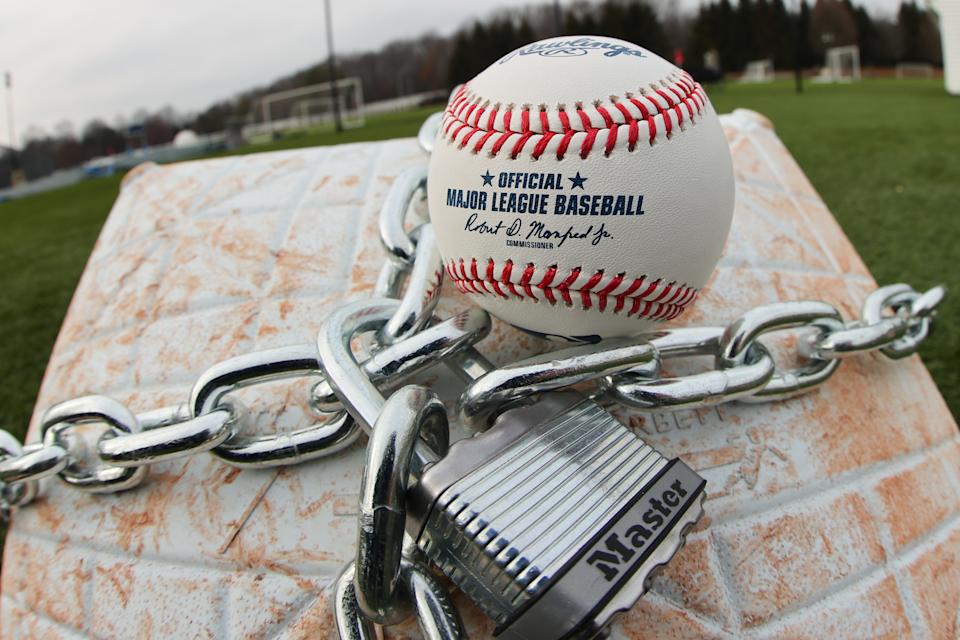

If Major League Baseball players and team owners cannot reach an agreement on the terms and conditions of the sport by next week, the 2022 regular season will almost certainly not start on time.

On Dec. 2, MLB franchise owners locked out the players in the sport’s first work stoppage since the 1994 strike. For the past several months, what that meant in practice was a very cold stove this offseason, after a brief glut of transactions.

But maybe you don’t follow baseball much in the winter anyway. Now that the sun is setting after 5 p.m., you’re expecting baseball to once again assume its patriotic role as a comforting omnipresence on TV. Not so fast.

Major leaguers cannot report to their teams’ camps or start playing a baseball season until one of two things happens: The club owners lift the lockout, or an agreement is reached. And the owners are not going to lift the lockout. With an unofficial Feb. 28 deadline set to get a deal done in time for a March 31 opening day, this week is pivotal.

Cue the proverbial freeze-frame record scratch over hastily snapped photos of labor lawyers. I’m sure you’re wondering how we got here.

Sports labor negotiations are pretty impenetrable to anyone other than the most dedicated consumers. Each incremental change to proposals is inherently narrow and esoteric and, except to the people involved, not especially consequential until the deal is done. Still, with the two sides planning to meet daily for the first time in these negotiations this week in Florida, those kinds of blow-by-blow updates will be under the microscope as the deadline for an on-time opening day approaches. So here’s what you need to know to follow along.

What MLB needs: A new collective bargaining agreement

Basically everything about baseball is governed by a collectively bargained agreement between ownership and the MLB Players Association that is renegotiated every few years (the exact length of the CBAs has varied but lately they’ve been five years). If a new deal is not reached before the outgoing CBA expires, the players can strike and team owners can implement a lockout. Ever since the ‘94 strike that canceled the World Series and saw the overall popularity of baseball take a hit, the work stoppages across sports have taken the form of lockouts, with the owners acting quickly to preempt an in-season strike.

For years now, a lockout this offseason has seemed all but inevitable. In this pre-lockout primer, we talk about some of the relevant history, up to and including the contentious 2020 season restart negotiations. But in short, changing trends and several CBAs widely considered to be losses for the union resulted in the average player’s salary stagnating or going down, even as revenues have gone up. In other words, even though baseball players are well-compensated and some achieve generational wealth, their slice of the industry pie has not kept pace with what club owners are making.

These concerns coalesced around a couple main issues: getting younger players paid more, commensurate with increasing early career production; and incentivizing more teams to compete every year. We have explored the biggest issues in detail — although you can unfortunately ignore the idea of tweaking the style of play for a more energized entertainment product.

To achieve those changes, the union wanted to create earlier paths to arbitration and free agency, guard against service time manipulation and disincentive tanking. The owners want an expanded postseason and an international draft, but the general sense is they would be happy to maintain something like the status quo.

There was little progress made in the lead up to the Dec. 1 expiration of the prior CBA. Early on, the league floated a salary floor/cap system, which would involve lowering the upper limit currently set by the luxury tax. It was rejected, as anticipated, by the union, which has remained ideologically opposed to a cap system since its inception. The league also introduced proposals to replace the reserve clause with an age-based system for reaching free agency and to replace arbitration with a formula for compensating players under team control.

With the two sides not only apart in numbers but essentially working in different, ahem, ballparks when the clock struck midnight on Dec. 2, the players were locked out.

How have negotiations gone during the lockout?

Both sides would accuse each other of being obstructionist in the weeks following the lockout. MLB waited more than a month after the lockout to make a new proposal, Rob Manfred later countered that “phones work both ways.” The league requested the assistance of a federal mediator — a voluntary and non-binding process of involving a third party in the negotiations — and the union rejected that request.

(In truth: They were never going to get a deal done in December or January. With the CBA expiration date in the rearview, the negotiations needed the pressure of a more threatening deadline to get anywhere, which didn’t exist until the scheduled resumption of baseball activity this month. That said, the union was never going to negotiate against itself, either. And a mediator would have been an unusual step at that point in the process, with so many issues still on the table. The league would say why not utilize every available resource, but the move read as largely theater.)

Over a handful of bargaining sessions on core economics held in New York City, they have inched toward one another. At the start of the lockout, the union was asking for three things that the league has said it will simply not change in this CBA: to reduce revenue sharing between teams, free agency before six years of service for some players and arbitration after two years of service.

Post-lockout, the union dropped its proposal for earlier free agency. Recently, the players reduced their ask for earlier arbitration — instead of applying to 100% of players with at least two years of service, it would apply to the top 80% of players with two years of service (currently, the top 22% are arbitration-eligible, known as Super Twos).

The league, meanwhile, has made what it considers to be meaningful concessions to address some of the union’s stated concerns. The owners have agreed in concept to an NBA-style draft lottery for the top spots to disincentivize tanking and bought into the concept of a bonus pool for rewarding top-performing pre-arbitration players. The league has also agreed to remove the direct draft pick penalty for teams that sign qualified free agents — in other words, removing a constraint on free agency that worked to subtly suppress the market.

Both sides have made proposals to address service time manipulation — the union’s rewards high-achieving players with a year of service, the league’s rewards teams that call up top prospects at the start of the season with extra draft picks.

Although nothing is guaranteed until the whole agreement is ratified, some subjects seem to be mutually agreeable, or at least tolerable. The designated hitter is coming to the National League. The postseason field could expand. Advertising patches could be added to uniforms.

But there is still a lot of ground to cover. In terms of pure numbers, they disagree on the major-league minimum salary, the amount of money in that pre-arb bonus pool and how many players it should apply to, the number of draft picks subject to the lottery, and the number of teams in the expanded postseason.

And then there’s the luxury tax, officially known as the competitive balance tax. The union, naturally, would like to see the threshold for paying raised significantly, to lessen the artificial downward pressure on the free agent market. The league is proposing a much smaller increase in the threshold, itself an issue for the union, but also a toughening of the sanctions against teams that cross it. The proposed stiffening of what is currently considered a soft cap — especially if it does not keep pace with industry revenue growth — is a source of significant frustration for the union.

Beyond that, there are a host of non “core economic” components of the CBA — including health and safety protocols and the joint drug agreement. Those issues are not as contentious and bargaining has progressed concurrently on them, but add that to the list of compromises now on the clock.

What’s happening now as spring training is delayed?

This week, the negotiations moved to Florida, where contingencies from both sides are planning to meet daily at Roger Dean Stadium, the spring training home of the St. Louis Cardinals and Miami Marlins.

In coverage, much is made of how long each session lasts. But very little bargaining happens across the table. Instead, the frequency of conversations and a willingness to caucus — discuss new proposals amongst their own members — and return to bargaining within the same day is a better indicator of acting with urgency.

And the matter is urgent. On Friday, the league announced that spring training games, scheduled to begin on Feb. 26, would not start until March 5 at the earliest. Recently, the league told the union that a deal would need to be done by Feb. 28 to preserve a March 31 opening day. It’s not clear if the union necessarily agrees with that timetable or whether there’s any flexibility, but Manfred has expressed a need for at least four weeks of spring training plus a couple extra days to ratify an agreement and get players to camps. In that time, teams will also need to round out an offseason’s worth of roster moves frozen in place for at least three months.

A ticking clock can grease the wheels of negotiations that seem all but deadlocked. Players get a per diem in spring training, but don’t start receiving paychecks until the regular season. Owners don’t have to worry about the lost revenue from gate receipts until the games themselves are lost. What has looked like a staring contest will quickly become a game of chicken with real stakes if no one blinks this this week. But of course, that’s also when each side feels they have the most leverage.