There are some sporting moments that the mind cannot project until they have materialised.

Across 10 years – 27 fights being the pugilists’ metric in this case – Tyson Fury had danced around, past and through opponents.

He had safely navigated his first 16 fights without encountering any significant adversity, and even in his 17th outing when he was knocked down for the first time, Fury was at once back to his feet, disregarding Neven Pajkic’s ferocious haymaker in a manner that seemed to suck all spirit out of the Serb. One round later, Fury had stopped him.

Still, the visual now existed: Fury falling, his 6’9” frame collapsing to the canvas.

READ MORE: The bloody fairytale behind Whyte’s long journey to Fury

It meant that, as many as seven years on, fans could project that image as they anticipated and debated the outcome of Fury’s first clash with Deontay Wilder – the opening salvo in a trilogy that almost made the action and twists of the original Star Wars films seem unambitious and predictable.

An image that remained beyond projection, however, was that of Fury not getting back up; not answering the referee’s count.

Despite Wilder’s unimpeachable efforts, that image is still just fantasy. It is still fiction.

In the rivals’ first fight, Fury’s 28th, just one second separated the image from the aperture – on two occasions. It was the case in the ninth round, and it was the case in the 12th. In the first instance, Wilder caught Fury with an overhand right, which looped down from above, and a grazing left hook. There was seemingly a delayed impact, with Fury eventually freezing for a fleeting moment – long enough for Wilder to put him down with the same scraping shot that started the combination.

In the 12th round, there was no grazing; no scraping. Again Wilder found his target with a right hand as he punched down on a crouching Fury, and the following left hook was as clean a strike as the American has ever landed – a shot that looked to have pulverised Fury. Again he beat referee Jack Reiss’ count by one. On this occasion, Fury had not taken his time intentionally to gather his senses. On this occasion, his senses had been scattered, his dramatic ascent from the canvas still inexplicable to this day.

In the pair’s trilogy bout last October, Fury was again put down twice. In the fourth round, the 33-year-old walked onto a stiff right straight that put the Briton out on his feet. Wilder then only had to touch Fury to put him down. Fury beat Russell Mora’s count by two. Later in the round, a short, clubbing right hook in a semi-clinch landed behind Fury’s ear, and again the champion tumbled to the mat. Again, the “Gypsy King” was fully responsive by the eight-count.

And so that image, of a referee waving their hands before Fury’s eyes, remains elusive.

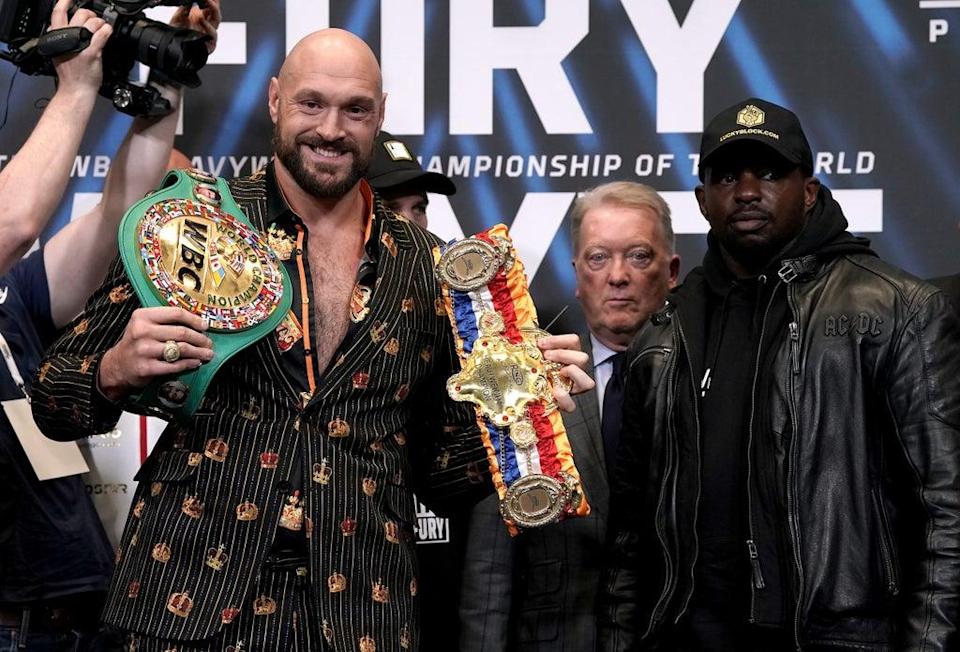

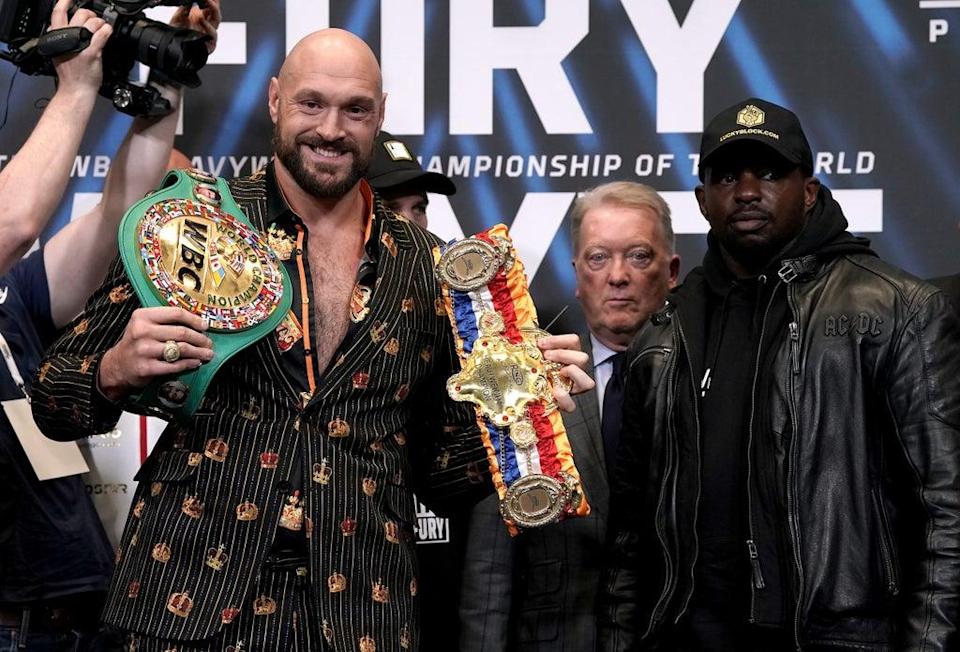

It is a major reason why so many fans find it difficult to envision Dillian Whyte conjuring a knockout blow this Saturday. Through 32 fights now, no one has managed it. No one has managed to beat Fury at all. As the 33-year-old has said repeatedly: Someone will have to nail him to the canvas, it seems.

And if the most hellacious hitter in heavyweight history could not do so across three contests, how can Whyte?

Well, firstly, Whyte is a better boxer than Wilder. That assertion has drawn some incredulous responses from casual followers of the sport in recent days, but it is far from unfounded. Whyte, 34, may not hit as hard as Wilder – perhaps no one on earth does – but the Briton is still a powerful puncher.

Just ask Alexander Povetkin, Derek Chisora, even Anthony Joshua whom Whyte stopped in an amateur meeting between the rivals. Nineteen of Whyte’s 28 wins have come via knockout, and the “Bodysnatcher” does a far better job at setting up the decisive strike than Wilder does.

Whyte, 11 years a professional, has cleaner footwork than Wilder, a greater ring IQ, and he is acquainted with Fury’s skillset from the compatriots’ time as sparring partners. Of course Fury’s game has evolved, as has Whyte’s, but their shared rounds in the ring will count for something. And when attempting to solve a puzzle as mystifying as beating Fury, ‘something’ is a start.

Whyte is also a tricky fighter, his movements not easy to predict and his lead left hook – widely regarded as his best weapon – often emerging out of nowhere. Again, ask Chisora. If Fury boxes southpaw, as he did all throughout his open workout this week, he will be more susceptible to that counter punch than if he operates out of an orthodox stance.

Furthermore, Whyte has a point to prove. He has waited years for this bout – for a shot at major heavyweight gold – and, according to the man himself, it cost him “a fortune in legal battles” to finally ensure his spot opposite Fury.

But even more dangerous than a fighter with a point to prove is a fighter free from pressure. And while it would be naive to suggest that there is no pressure on Whyte’s shoulders whatsoever, especially considering his apparent expenditure on lawyers and the incentive of a financial bonus if he wins at Wembley, the challenger has been counted out to such an extent here that he should be able to box freely.

If he does so, perhaps it will be Fury who is finally counted out, in the only sense that matters in this sport.

Whyte has been dismissed as having little more than a puncher’s chance against the WBC heavyweight champion. Worse boxers than Whyte have won bouts this big with that alone.

The narrative that Fury will dance around, past and maybe even through Whyte is understandable. On the eve of one of the biggest fights in British heavyweight history, however, it is hard to shake the feeling that Whyte will create the kind of chaos that Wilder did against Fury.

Do not be surprised if Fury is again forced to depend on his heart as much as his hands in trying to beat Whyte. If all goes to plan for the challenger, Saturday will finally be the night that Fury’s heart is not enough, and a new image crosses the aperture.