Bill Russell was a late bloomer. Before the college basketball accolades and a pair of national championships, before the 11 NBA titles and five MVPs, before he became the most fearsome defensive player ever and a man firmly entrenched in the conversation for the greatest player of all time, there was a gangly, 5-foot-10 kid from Oakland’s McClymonds High School who believed a job in the shipyards was in his future.

There proved to be so much more.

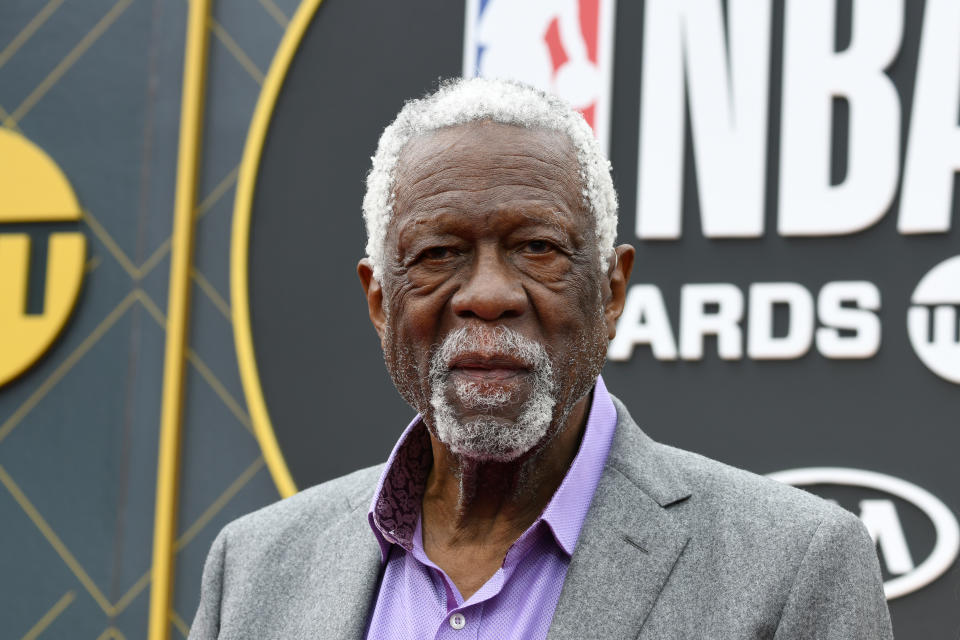

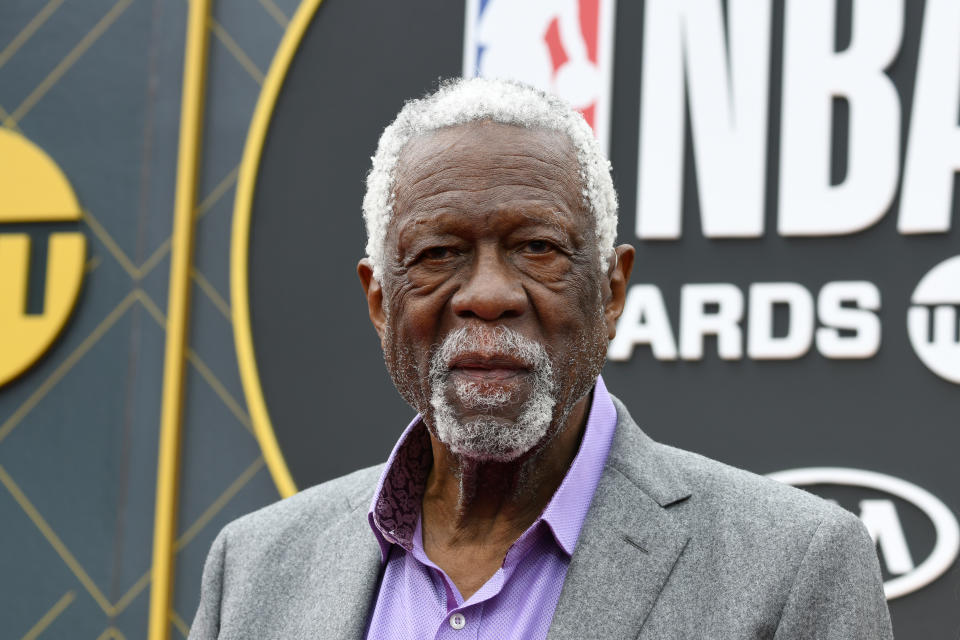

William Felton Russell died Sunday with his wife Jeannine at his side. He was 88. The greatest winner in professional sports — Russell’s 11 championships in 13 seasons is a mark unlikely to ever be matched — had a career that included 12 All-Star appearances and an Olympic gold medal in 1956. He was at his best in the biggest moments: In 30 elimination games at the college, pro and Olympic levels, Russell was a staggering 28-2.

Said Tommy Heinsohn, a teammate of Russell’s in Boston: “He would do superhuman things when they needed to be done.”

Russell was born on Feb. 12, 1934, in Monroe, Louisiana, where racism was deep-seated. Russell’s parents, Charlie and Katie, knew people there who had been born slaves; Black men and women were forced to wait in line behind whites at places like drug stores and gas stations, and Katie Russell, dressed in a new suit she made for herself, was once stopped by police and told not to wear “white women clothes,” according to a feature on Russell written in 2001.

Russell’s family moved to Oakland in the 1940s, where basketball first took hold. Russell was a gifted athlete — his Celtics teammate, John Havlicek, said Russell could have been a champion decathlete — but basketball came slowly. As a sophomore at McClymonds, Russell was nearly cut from the junior varsity team. He suited up for only half the games that season.

Russell didn’t start until his senior year, and even then scholarship offers were scarce. Phil Woolpert, the head coach at nearby University of San Francisco, was the only coach to offer him a scholarship. Under the guidance of Woolpert and assistant coach Ross Giudice — “Much of what I am, I owe to Ross,” Russell wrote in his 1966 autobiography “Go Up for Glory” — Russell transformed from a clumsy kid who struggled to make layups into one of college basketball’s most dominant players. Backboned by Russell, the Dons won two college basketball championships and strung together a winning streak of 55 straight games.

NBA team executives took notice. One was Red Auerbach, Boston’s grizzly head coach. In 1956, Rochester held the No. 1 pick in the draft. St. Louis had No. 2, and Boston had arranged a trade to move up — if Russell were still on the board. As legend has it, Walter Brown, the Celtics owner who co-owned the popular Ice Capades, made a deal with Rochester owner Lester Harrison: Don’t draft Russell, and the Ice Capades would commit to performing at Rochester’s arena.

The Royals drafted Sihugo Green. The Celtics sent Ed Macauley and the player rights of Cliff Hagan to St. Louis in exchange for the second pick — and the rights to Russell.

Russell was a defensive pioneer. He popularized shot-blocking. “I was an innovator,” Russell told The New York Times. “I started blocking shots although I had never seen a shot blocked before that. The first time I did that in a game, my coach called timeout and said, ‘No good defensive player ever leaves his feet.’ ” Russell was a master of tip-blocking, tapping shots to his teammates to ignite fast breaks instead of swatting shots into the stands.

Much of what defines today’s great defensive players began with Russell. His ability to slide across the lane to provide help defense. His ability to alter shots. Said Auerbach: “He put a whole new sound in [the] game. The sound of footsteps.”

To his teammates, Russell was gregarious, known for a bellowing laugh. To the those outside the locker room, Russell was often withdrawn. “Jekyll and Hyde,” Bob Cousy once said. Russell had a complicated relationship with Boston. He often said he didn’t play for Boston — he played for the Celtics. Russell lived in Reading, Massachusetts, a town just north of the city. One night, Russell came home to find his house vandalized. Racial epithets were spray-painted on his walls. Burglars poured beer on his pool table, smashed in his trophy case and defecated on his bed.

“Every time the Celtics went out on the road, vandals would come and tip over our garbage cans,” Russell’s daughter, Karen, wrote in 1987. “My father went to the police station to complain. The police told him that raccoons were responsible, so he asked where he could apply for a gun permit. The raccoons never came back.”

Russell was never just a basketball player; in airports, he often replied, “No,” when asked if he was. Everywhere, Russell stood up against inequality. Once, in Marion, Indiana, Russell was presented with the key to the city. Later that same night, Russell was refused service at a local restaurant. He immediately drove to the mayor’s house and gave back the key.

Few athletes were as outspoken as Russell on controversial subjects. He fought back against the racism he dealt with in Boston. He criticized the NBA for what he saw as quotas on the number of Black players in the league. In 1961, after a restaurant in Lexington, Kentucky, refused to serve some of the Celtics’ Black players before an exhibition game, Russell organized a boycott of the game. In 1975, he declined to attend his Hall of Fame induction, later calling it insulting to all the Black players who were not inducted before him.

He refused to sign autographs, but welcomed a conversation.

“What I’m resentful of, you know, is when they say you owe the public this and owe the public that,” Russell told the Saturday Evening Post in 1964. “You owe the public the same thing it owes you. Nothing. I’d say I’m like most people in this type of life; I have an enlarged ego. I refuse to misrepresent myself. I refuse to smile and be nice to the kiddies. I don’t think it is incumbent upon me to set a good example for anybody’s kids but my own.”

On the court, Russell’s career was highlighted by his rivalry with Wilt Chamberlain. At 7-foot-1, 275 pounds, Chamberlain was significantly bigger than Russell and arguably just as quick. While Chamberlain had the statistical edge against Russell — 28.7 points and 28.7 rebounds in a whopping 142 matchups — Russell’s teams routinely came out on top. Russell’s Celtics were 85-57 against Wilt; in eight playoff series against Chamberlain, Russell lost only once.

Russell retired in 1969, serving the last three seasons as Boston’s player-coach. He returned to the coaching ranks in 1973, in Seattle, where he stayed for four seasons. In 1987, he took over the Sacramento Kings, but lasted just 58 games before moving to the front office. He was fired in 1989. He didn’t return to the NBA.

In retirement, Russell continued to be recognized for his achievements. He was named one of the NBA’s 50 greatest players in 1996 and had the Finals MVP trophy named after him in 1999. In 2011, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, and in 2013, Boston unveiled a statue in his honor.

For all he accomplished, he is best known for this: On the court or off, Bill Russell never backed down.