INDIANAPOLIS — When Sam Smith died in his modest home on the east side of Indianapolis, he died a man who not long before had swallowed his pride and made a phone call to ask for gas money. He died a man who had to make a call to ask for help with funeral expenses for his daughter.

He died a man who was an American Basketball Association player, a pioneer who blazed the trail for what the NBA is today.

But basketball ended for Smith. After winning an ABA championship with the Utah Stars, he got a job as a security supervisor at the Ford assembly plant in Indianapolis. Years passed. Times got harder. More years passed.

As Smith’s 50th reunion for his Kentucky Wesleyan NCAA Division II championship approached five years ago, he called the Dropping Dimes Foundation, which helps struggling ABA players and their families.

Smith didn’t have the money to get to his reunion, he told Dropping Dimes CEO and founder Scott Tarter. He needed a loan, and insisted it be a loan, for $250. Dropping Dimes gave him the money and told him it was a gift, not a loan.

Smith waited, hoping he wouldn’t have to make another call to Dropping Dimes. Hoping for the $2,000 a month pension he said he was owed by the NBA for his five years playing in the ABA, which merged with the NBA in 1976.

Two years later, Smith had to make another call. His daughter had died a single mother, leaving her 5-year-old son with autism for Smith and his wife, Helen, to raise.

STAY UP-TO-DATE: Subscribe to our Sports newsletter now!

“He called me up in tears,” said Tarter. Smith didn’t have the money to pay for his daughter’s funeral.

Dropping Dimes helped and Smith waited some more, hoping. The pension from the NBA never came.

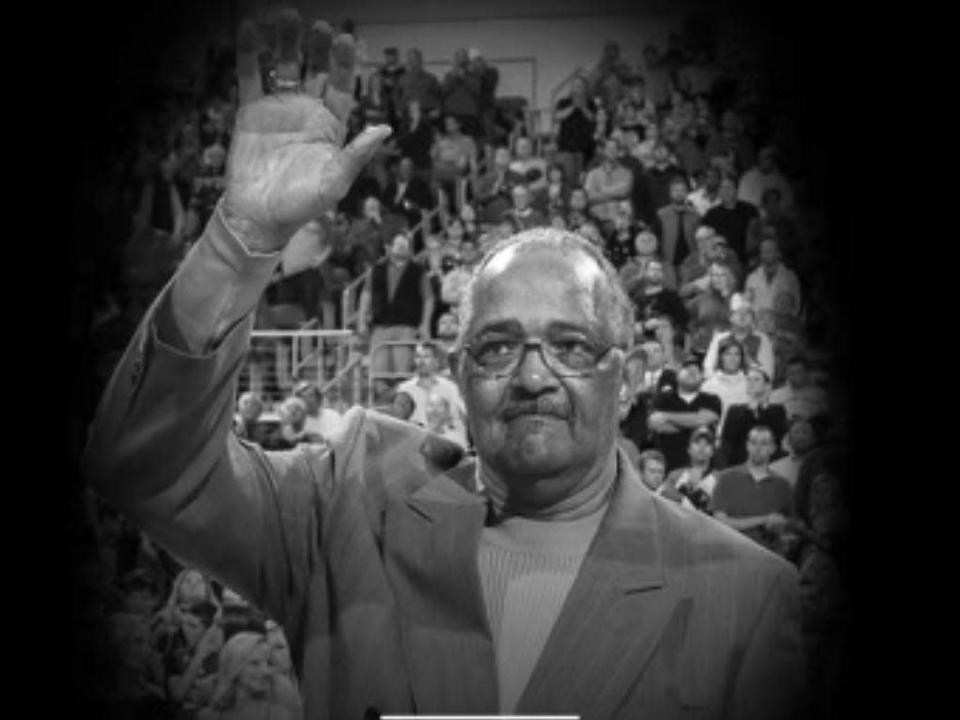

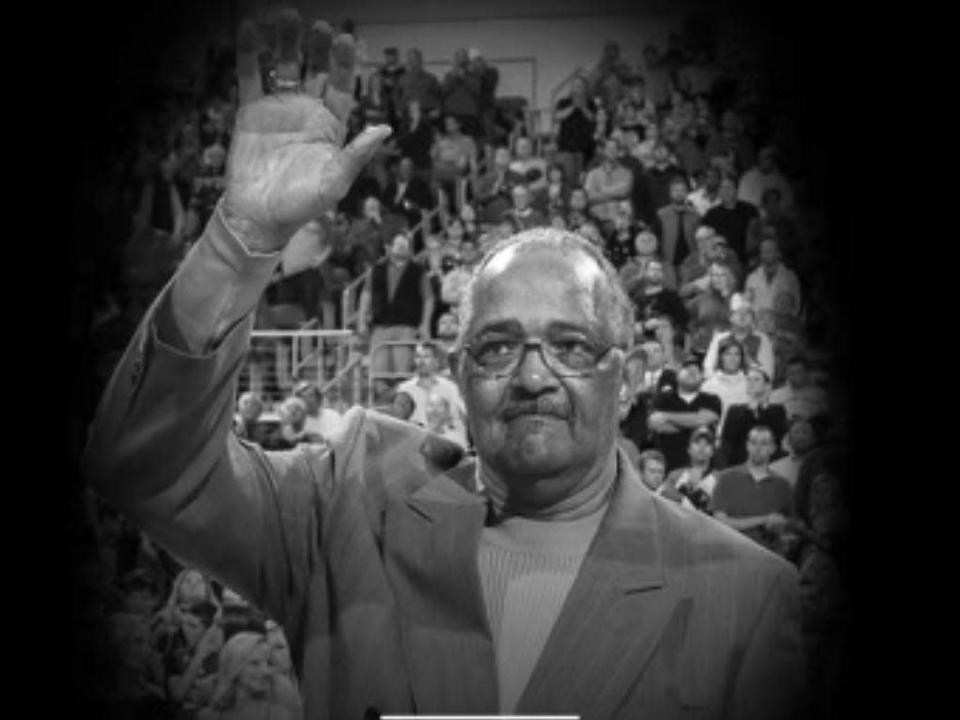

Weeks before Smith died at the age of 79 on May 18, lying in a hospital bed next to an ABA basketball, a chilling photo was taken. It was a photo Smith wanted people to see.

“He grabbed my arm and pulled me closer to him,” said Tarter, who took the photo. “And he said, ‘I would do anything to get the NBA to help these guys.”

Maybe the photo would help them. Smith knew it was too late for him.

More: NBA says it’s in discussions to help former ABA players: ‘They’ve been waiting a long time’

More: Former ABA players struggling and running out of time: ‘The NBA’s waiting for us to die off’

‘It would have been life changing’

These former ABA players are in their late 60s, 70s and 80s. Some are homeless, living under bridges. Some die alone with no money for a gravestone. Others can’t even afford dentures or a new suit to go to church.

Smith considered himself lucky compared to his former teammates. At least he had the health insurance from Ford. But $2,000 a month would have been a windfall for the family, said Smith’s wife, Helen.

“It would have been life-changing,” she said. “Because we were living. We were getting everything paid, but we couldn’t do a lot more.”

When the ABA disbanded in 1976, merging with the NBA, four of its 11 teams were absorbed by the NBA — the Pacers, Nuggets, New York Nets and San Antonio Spurs. The players who didn’t find a long-term spot in the NBA were left with no pension, salaries shut off and health insurance gone.

NBA players have had a pension plan since 1965. Any player with at least three years of service in the league is eligible for a monthly payment and access to other benefits, such as life-long healthcare coverage, a college-tuition reimbursement program and more.

Many of the ABA players never got to the NBA after the merger. Some did, but played only a year or two. Without those three years of service, it doesn’t matter how much they contributed to the ABA, they are left without that payout.

Smith is one of those who gave his all for a league and ended up with nothing.

“I am so mad at the NBA,” said Tarter. “Here is a guy who should have been enjoying a pension and instead … another one is gone.”

In February 2021, after the IndyStar published a story revealing a majority of the ABA players who are struggling are Black, the NBA responded.

“We are in discussions with the Dropping Dimes Foundation on this issue,” NBA spokesman Tim Frank said at the time. Frank confirmed Wednesday that those discussions continue.

The amount of money it would take for the NBA to fund what Dropping Dimes is asking for in ABA pensions, $400 a month for each season of play, is at most $35 million, Tarter said. That amounts to one third of what the NBA donates to charity each year from the player fines the league takes in, he said.

There are 138 ABA players still alive who Dropping Dimes says should be getting pensions.

Michael Husain, a producer and director with Good Vibes Media, is working on a documentary “The Waiting Game,” chronicling the struggles of former ABA players and their fight for pensions.

Many players have told him, Husain said, “I don’t want to believe it, but in some ways, it feels like they are just waiting for us to pass.”

‘It was hard for him to ask for help’

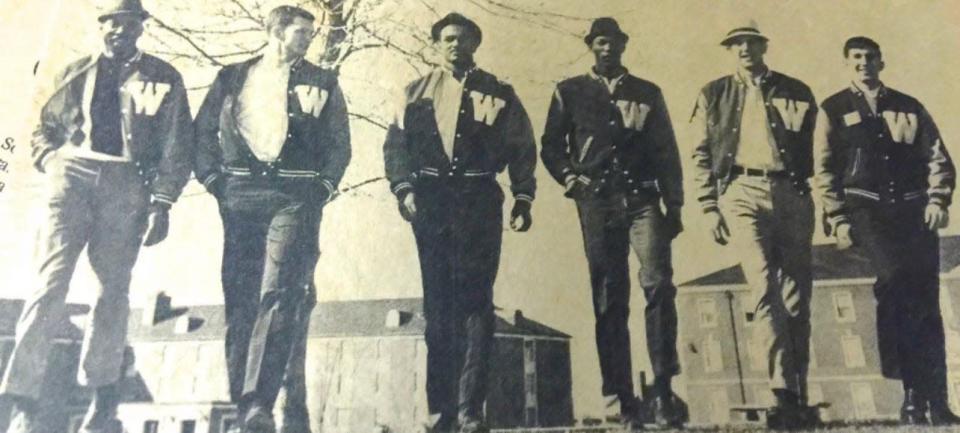

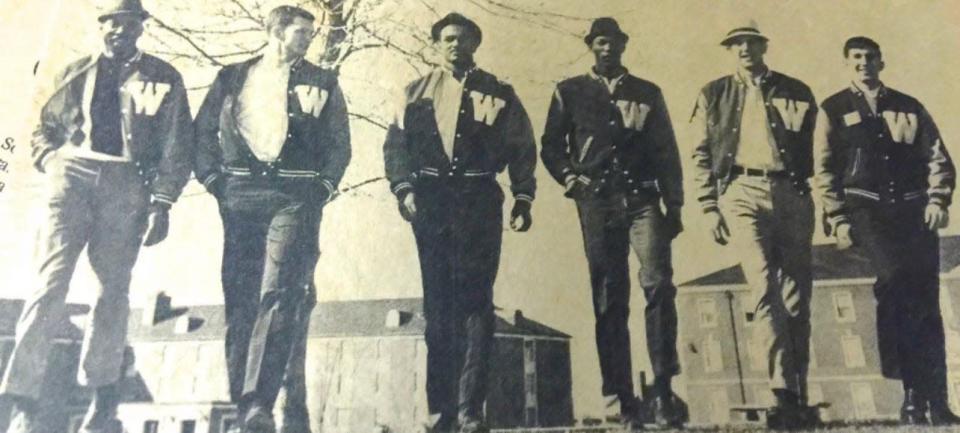

Life was going to be amazing for Smith, a 6-7 forward born in Hazard, Kentucky. He played football and basketball for Hazard High and was a Kentucky State basketball All-Star in 1962.

He became the first Black player to start for the University of Louisville and after transferring to Kentucky Wesleyan, he won a national title in 1966.

In the final 15 seconds of the game, the score tied 51-51, Smith made the game-winning basket for the national championship. Smith received two All-American selections during his college career and was named the All-NCAA South Region Most Outstanding Player two times. He was a member of the NCAA championship All-Tournament Team in 1967.

Later that year, he was drafted by the Cincinnati Royals with the 28th pick of the 1967 NBA draft, but chose to go with the other pro basketball league, the ABA.

He signed to play with the Minnesota Muskies. In his pro debut, he scored 24 points and grabbed 14 rebounds against the Kentucky Colonels. From 1967 to 1971, Smith played in the ABA with the Muskies, Kentucky Colonels and Utah Stars. He won a championship with the Stars in 1971.

But the next season, on a road trip with the Stars, Smith suffered an anxiety attack. Doctors at first thought it was a heart attack, said Helen. He decided to quit basketball.

It was sad for Smith, who had dreamed of a long career in pro basketball, but he took it in stride. He went to work the night shift at Ford and cared for his family, including Helen, son Sammy and daughter Felicia.

“He was a really humble and amazing guy,” said Tarter. “And it was really hard for him to ask for help.”

Smith hated asking for help. And until his dying day, he told anyone who would listen that the NBA should step up.

‘This isn’t a gift. He earned it.’

Quiet by nature, Smith wasn’t quiet about what he thought he deserved from the NBA. He would often meet Tarter at Steak N Shake for happy hour (half price milkshakes) and discuss what could be done to help struggling ABA players.

Even as his life was ending, Smith was all-in on doing anything he could. That’s why he wanted that photo on his hospital bed weeks before his death to mean something.

Smith had been healthy, for the most part. Twenty years ago, he had stents put in his heart, but he was living just fine with that, said Helen.

On March 31, he fell after being sedated at a dentist appointment and broke his femur. After surgery and complications, Smith was sent to a nursing home.

His potassium levels dropped and he was sent back to the hospital. While there, doctors told Helen that Smith had suffered a stroke.

On May 16, Smith was sent home on hospice

“I knew then they had just given up on him,” said Helen. “I haven’t processed his death because I have no reason for it.”

The death certificate says Smith died of congestive heart failure. Helen and Smith’s son, Sammy, were by his side when he died the night of May 18.

All Helen could think was what a great loss this was, how she felt about the man she met him in the early 1960s.

“My thing was what’s not to like?” she said. “He was a gentleman. He was just sweet. He was quiet, kind of shy, but he was also uncompromising. He said exactly what he meant and meant what he said.”

Even as he waited for his pension, and was outspoken about what he believed ABA players deserved, Smith would watch the NBA. He died during the conference finals.

“It broke my heart seeing what a big fan he was of the NBA and the players,” Tarter said. “He held no grudges and held nothing against them.”

But to watch the advertising, the promotions, the global television rights and to see Smith wasting away, Tarter said, was heartbreaking.

“He died without any recognition, without any respect, without any pension,” he said.

That $2,000 a month for Smith “would have made a tremendous impact on his family,” said Husain. “This is money he earned. It isn’t a gift. He earned it.”

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Sam Smith, former ABA player, dies waiting on pension from NBA